El Faro's Final Maneuvers Revisited

The National Transportation Safety Board released has released a 16-page illustrated digest summarizing the critical events and decisions that led to the October 1, 2015 sinking of El Faro and the loss of all 33 crewmembers. The digest reviews the voyage, the vessel's final maneuvers and examines the more than 60 recommendations issued throughout the NTSB’s investigation of the sinking.

Timeline of the last hours

At 0409 on October 1, the captain arrived on the bridge, shortly thereafter telling the chief mate that the only way to correct the starboard list was to transfer water to the port side ramp tank.

At 0440, the chief mate called the captain over the electric telephone. He said, “The chief engineer just called . . . something about the list and oil levels.” He might have tried to gauge the list with a clinometer (“can’t even see the [level/bubble]”).

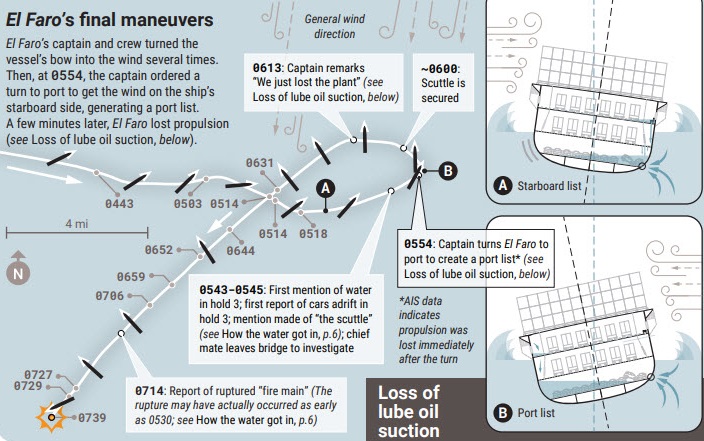

At 0443, the captain said to put the vessel into hand steering so it could be steered into the wind to try “to take the list off.” The chief mate turned the vessel northward to 65°. The captain took the conn and ordered a further change to 50° (farther into the wind). The vessel’s speed dropped to 7.5 knots.

At 0445, the captain downloaded a BVS weather file that was available at 2304 the night before. Its position and forecast information for Joaquin was consistent with an National Hurricane Center (NHC) advisory delivered to the ship via Sat-C almost 12 hours before. Less than two minutes later, El Faro’s Sat-C terminal received an NHC advisory with up-to-date position, wind speed, and storm track information.

At 0503, the captain, comparing the updated Sat-C weather information with his most recent download of BVS, said he was getting “conflicting reports as to where the center of the storm is.” At that time, another BVS weather file became available, but the captain did not download it until an hour later (0609).

Beginning at 0510, the captain and the riding gang supervisor—an off-duty chief engineer—discussed the extent of the starboard list, and the captain asked how the list was affecting “operations as far as lube oil(s).”

At 0514, shortly after the captain said their speed was maintaining at 11 knots, he turned the ship into the wind again.

By 0518, the vessel’s speed had dropped to 5.8 knots. It was now moving with a pronounced starboard list; in hurricane-force wind, rain, and waves; with zero visibility and an untrustworthy anemometer.

At 0543, the captain received a call from the chief engineer that there was a problem in cargo hold 3. He told the chief mate to go to the hold and start pumping. The crew continuously pumped the hold 3 bilges from this point onward.

At 0544, the captain was heard on the VDR saying “We got cars loose,” likely referring to automobiles that had broken free from their lashings. The automobile-lashing arrangement did not meet the requirements of the vessel’s approved cargo-securing manual, making automobiles more likely to shift in heavy weather. The crew found that a scuttle (small watertight hatch) on the second deck, starboard side, was open and seawater on deck was flowing over it and down into cargo hold 3. The ship’s list to starboard was causing seawater to pool near the scuttle located on the starboard side. The captain told an engineer to begin transferring ballast water from the starboard ramp tank to the port ramp tank.

At 0554, the captain ordered a turn to port to put the wind on the ship’s starboard side, thereby generating a port list so the crew could better investigate the source of the flooding in cargo hold 3. This was also the most aggressive of several turns that followed the first conversation about oil levels at about 0440. Shortly after the turn to port, the chief mate reported that they had secured the scuttle on the starboard side of the second deck. The vessel was now listing to port and its speed was 2.8 knots.

At 0602, the second mate said she heard alarms sound in the engine room. At 0609, the captain downloaded the BVS weather file, which was sent at 0502, whose information about the hurricane (position, forecast track, and intensity) was consistent with an NHC advisory the ship had received via SAT-C about seven hours before. He ordered the engineers to transfer bilge water back to the starboard ramp tank, saying “I’m not liking this list.” Cargo hold 3 continued to take on water and the ship continued to lose speed, despite continuous bilge pumping efforts by the crew.

At 0613, the captain said he thought that the vessel had lost propulsion.

At 0616, the engine room called. Although the conversation from the engine room was not recorded on the VDR, the captain asked, “so . . . is there any chance of gettin’ it back online?” It is likely that a suction pipe leading to the lube oil service pump had taken in air instead of oil. The port list, coupled with the vessel’s motion, resulted in a loss of oil pressure that caused the main engine to shut down. Once propulsion was permanently lost, El Faro was pushed sideways by the wind and waves.

At 0631, the captain said he wanted “everybody up.” He had the second mate compose, but not send, a distress message.

By 0644, El Faro’s bow was pointed not into the wind, but perpendicular to it. Minutes later, the captain mentioned “significant” flooding in hold 3, but said that he did not intend to abandon ship, saying there was “no need to ring the general alarm yet.”

At 0659 the captain called a designated person (DP) ashore and left a message. Seven minutes later, the captain was connected to the DP and reported a marine emergency. When the call ended at 0712, the captain had the second mate send the distress message. The increasingly large induced list to port from wind and increasing flood water levels in hold 3, combined with the vessel’s rolling in the storm seas, likely caused seawater to enter cargo hold ventilation openings in the hull. It was possible to close these openings, but they were left open during the event; they were not considered downflooding points in any available guidance documents. Seawater poured into hold 3 and then into hold 2A and 2.

At 0714, the chief mate told the captain that the chief engineer had said that, “something hit the fire main, got it ruptured, hard.” One or more of the vehicles in hold 3 had likely struck the emergency fire pump, or “fire main” piping, at the starboard side of hold 3. The inlet piping to the fire main system was designed to supply seawater to the suction side of the emergency fire pump. With a severe breach, seawater would have flowed into hold 3 at a rate that would inevitably overwhelm the capabilities of El Faro’s bilge pumps. It is likely that the piping was breached earlier than 0714, based on the continued flooding of hold 3 after the scuttle was secured and the hold was being dewatered by bilge pumps. (Vehicles had likely been adrift at least as early as 0544, when the captain reported “cars loose.”) Rather than mustering the entire crew, the captain and a few officers continued efforts to diagnose the problem, though they made no reference to consulting a damage control plan or booklet.

Finally, at 0727, the captain ordered ringing of the general alarm. A minute later, the chief mate advised the captain over the radio that the crew was mustering on the starboard side, and at 0729, the captain ordered the crew to abandon ship. He ordered the liferafts thrown overboard at 0731 and told everyone to get into their rafts and stay together.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

The recording ended at 0739.

About three minutes after El Faro’s VDR stopped recording, a reconnaissance aircraft estimated a 10-second average surface wind speed of 117 knots about 21 nautical miles south of El Faro’s last known position. At 0800, Joaquin’s center was estimated to be about 22 nautical miles south-southeast of El Faro’s last known position, according to an NHC post-storm assessment.