Drought in Texas Reveals History of America's WWI Shipbuilding Surge

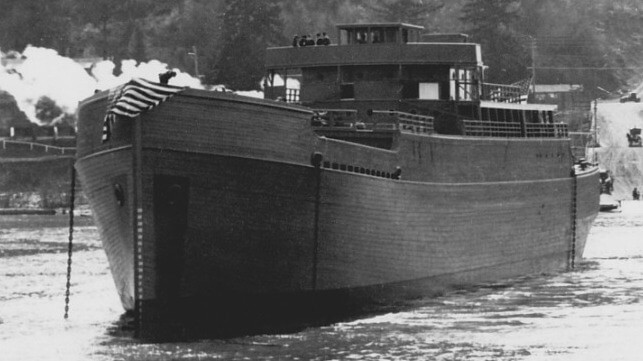

Texas' prolonged drought has revealed a long-lost relic of the early 20th century on the Neches River. Local resident Bill Milner spotted the wreckage of a ship in the shoals while on a Jet-Ski outing near the town of Evadale, and he reported the find to a local museum. The vessel was large, and made of wood, suggesting a much earlier era. His first thought was that it was a wooden barge or riverboat - but it turned out to be something much more unusual.

According to the Texas Historical Commission, the wreck is one of many on the Neches that came from a World War I shipbuilding program run by the Emergency Fleet Corporation. When the United States joined the war in 1917, it was badly short of merchant tonnage to carry troops and equipment across the Atlantic. British shipping provided much of the transport capacity for U.S. forces until the end of the war, but loss rates were extreme. Germany's U-boats took a severe toll on shipping in the North Atlantic, and at one point British shipping could expect to lose one out of four vessels on any given round trip voyage.

The Emergency Fleet Corporation attempted to catch up with innovative strategies - including wooden shipbuilding. In that era, a wooden-hulled ship was not unusual, and it offered some advantages. With steel in short supply for the war effort, some of the EFC's leaders believed that wood would be an effective alternative for ships that only had to make a one-way voyage across the Atlantic to justify their cost. "The Germans were sinking vessels so fast that it became apparent we must adopt extraordinary methods," explained former Shipping Board chairman Edward N. Hurley after the war.

The program called for the construction of over 1,000 of these wooden ships with a total capacity of three million deadweight tonnes. The skills and materials to produce wooden ships at scale were available on the Gulf Coast, and many were built along the Neches.

These ships were never intended to be commercially useful in peacetime, and they were designed solely to offset wartime losses. About 320 were completed at the war's end, and though more than 260 had successfully carried cargo overseas, they were immediately obsolete. These hulks were widely criticized as a visible example of government waste. Hundreds were laid up and sold for scrap; in one prominent example, a recycler burned 30 of them at a time on the Potomac to salvage the metal components.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Over one dozen hulls were in various stages of construction at yards near Beaumont when the war ended, and they were left unfinished. In the 1920s, they were pushed off into the Neches and Sabine Rivers, where they slowly deteriorated over the span of a century.

The program's creators defended the wooden fleet as a legitimate wartime expense. "Although the wood ships never could compete with fast steel cargo carriers in the trans-Atlantic trade, they made more than enough voyages to convince us that our policy in building them was not mistaken," Hurley wrote in his history of the war effort.