Counting "Invisible" Containers

Industry analyst Dynamar says 124 carriers are acting as feeder container operators worldwide, deploying an annual trade capacity of 43 million TEUs. Generally, feeder containers do not appear in trade statistics, although they count double in port statistics.

Dynamar says 20 dominant transhipment ports handle 24 million TEUs of these “invisible” containers, in the 2018 edition of: Transhipment and Feedering 2018 - Trades and Operators - Ships and Hubs.

Feedering is the first or last maritime leg of an ocean borne container transport where the ports of loading or discharge of the mainline container ship are not the same as the ultimate origin or destination port of the container. Feedering is a short haul trade between a deepsea hub and regional ports that do not have sufficient cargo to warrant a direct call from a mainline service, or are lacking the infrastructure to handle larger vessels. As the regional part of the global container transport system, feedering is an integrated part of the door-to-door transport chain.

Why is feedering an invisible trade? It is “commercial” full containers that are being counted to assess the world container trade, which reached around 168 million TEUs in 2017. Commercial full containers are shipped on a Bill of Lading issued by the shipping company to the shipper. This Bill of Lading covers the carriage of the boxes from their first port of loading until the ultimate port of destination.

In contrast, a feeder move constitutes an operational port-to-port activity, arranged by the mainline carrier using the services of a feeder company. Feeder containers usually travel on a Service Bill of Lading issued by the feeder operator to his principal, the mainline carrier. In the case of feedering, the container, full or empty, is the cargo. Relevant statistics do no exists, but the total number of feedered containers could be estimated at 65 million TEUs worldwide.

Feeder boxes count double in port-handled container statistics, as both the move from the mainline vessel and the handling into the feeder are counted. Feedering involves transhipment: containers are discharged at a direct port of call, the hub, for on-carriage to their final destination, the feeder port. The direct mainline port of call serving as a hub can either be a gateway, a port serving its direct hinterland, or a port specifically built for processing transhipment. If used for transhipment, they are both referred to as a hub. A port handling more than 50 percent transhipment is considered a dominant transhipment port.

In 2017, around 25 ports could be considered dominant transhipment ports. The Mediterranean accommodates the largest number of such hubs: nine with an average transhipment share of 79 percent, followed by the Far East: five dominant transhipment ports, average 71 percent. The hub port with the highest transhipment shares are Freeport (Bahamas, 99 percent) and Marsaxlokk (Malta, 95 percent). Singapore is, undisputed, the one with the highest transhipment volume: 28.5 million TEUs in 2017. Only two such ports can be found in North Europe: Bremerhaven (57 percent) and Wilhelmshaven/ JadeWeserPort (70 percent).

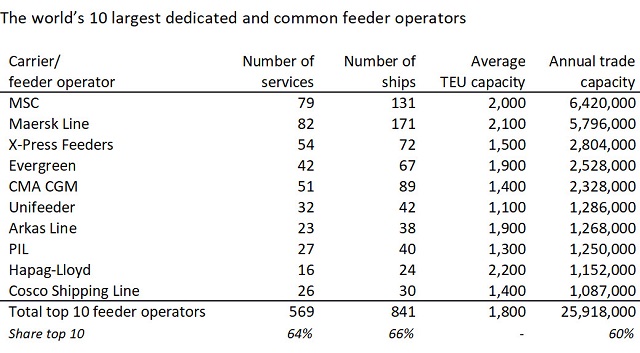

Dynamar has identified 124 shipping companies worldwide,offering feeder services. 13 dedicated carriers deploy the largest ships serving as a feeder. Another four, CMA CGM, Maersk Line, PIL and ZIM, operate their feedering business under separate brands also active as common carriers.

Most, if not nearly all, companies carrying feeder containers are also taking regional cargo. It is believed that only X-Press Feeders, present in all trades, is the only pure feeder operator. It is also the world’s third largest feeder operator.

Do feeder ships exist? Feeder is basically a vessel classification used in the chartering industry, comprising four different capacity categories of between 1,000 TEUs and 2,750 TEUs. Essentially, any container ship can carry any container. Equally, feeder containers are similar to any other container. That said, in North Europe, container vessels have been designed and built with the specific purpose of feedering in mind. A famous ship in this respect is the Sietas “type 168,” a partly hatchcoverless vessel. More than forty “type 168” units have been built with a capacity of 670 TEUs, plus another few of 1,010 TEUs each. Many of them are Ice-class A1, a requirement to serve the Baltic trades during the winter season.

As intra-Europe containers come in a large variety of types, this, in particular, is there where often non-cellular, i.e. multipurpose feeder vessels are being deployed. However, in general, cellular container ships on the intra-Europe routes also require a flexible stowage configuration. This is an absolute need to carry, next to the common 20’ and 40’ units, such odd sizes as 30’ boxes, 40’ high cubes, 45’ pallet-wides and half height tanks.

The adage that, rather than the size of the mainline ship, the capability of a port decides upon the size of the feeder ship is unchanged. As many feeder ports have become more capable over time, they have allowed the feeder ship to grow larger too. However, it is 1,300 TEUs on average today against 700 TEUs 10 years ago for the common feeder ship. And 2,000 TEUs average against 1,200 TEUs for those employed by the dedicated operator. There are always exceptions: recently MSC used a 10,000-TEU ship on to Antwerp-Eastern Baltic feeder route.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

The size of the mainline vessel too plays a role. Their much larger call sizes require either more or larger, feeder vessels to distribute the cargo. As of early June 2018, the North Europe-Far East trade counted 18 weekly services, operated by nine different carriers organized in three Alliances (2M/6 services, Ocean Alliance/6, THE Alliance/5), plus Hyundai operating standalone. The average capacity of all 205 ships employed was 15,000 TEUs, and total shipboard space was 3,183,000 TEUs. The largest vessel was 21,400-TEU (CoscoLS/OOCL); the smallest one 4,100-TEU (Hyundai). The average number of North European mainline port calls is four; any cargo on board for other ports has to be feedered.