At WorkBoat 2025, Cost Control Takes Center Stage

American operators often get sticker shock when pricing out new vessel tonnage these days, and at WorkBoat 2025, vessel affordability was at the top of the agenda. How can yards bring down the cost of construction, and how can owners, naval architects and engineers write specs for value - not just perfection? TME asked around the show to find out, and came away with a few answers - some well-known, some less so.

Well-known solutions

First, there are a few often-discussed ways to shave down the price of a newbuild, all having to do with limiting customization and change. These were heard often at WorkBoat:

- Standardize and buy into series production. Off-the-shelf series builds are common at some European and Asian shipbuilders, and this allows the shipyad to leverage lessons-learned for assembly and greater buying power for components.This idea can be a hurdle for American owners: Many have strong and well-founded preferences for certain engine OEMs and equipment suppliers. It's a change in mindset to buy the same off-the-shelf vessel, but it's far cheaper, multiple panelists agreed at ABS' offshore forum.

- Get the design right with expert guidance, then leave it be. Concurrent design and construction speeds up production, but any major changes mid-build can have cascading effects and may force rework - with impacts on delivery timeline and cost.

- Build government ships with commercial methods. The Vessel Construction Manager (VCM) model pioneered by MARAD, Tote Services and Philly Shipyard is an often-cited way to do this. By putting an owner's representative in charge of the paperwork and the build, the government gets a good vessel at a good price, and the shipbuilder gets freedom to work. A VCM contract can also be structured to unlock government infrastructure support for the yard when key milestones are achieved, says Jeff Vogel, Vice President of Legal at Tote Services. This provides incentives for performance as well as investment in the long-term health of the shipbuilder.

Less-discussed solutions

There were also some less-often-heard ways to get about cost reduction too - some easier to execute than others, and some rather controversial:

- Cultural change brought by foreign investors. The Korean shipbuilding method emphasizes individual employee accountability for meeting schedule, down to the level of each panel, module, frontline worker and weekly target. This sets a new expectation: there will be long hours when needed to keep the project on track; there will be accountability up and down the line for schedule slip; and in turn, there will be more overtime wages and more opportunity for advancement, explains Tote Services' Vogel.

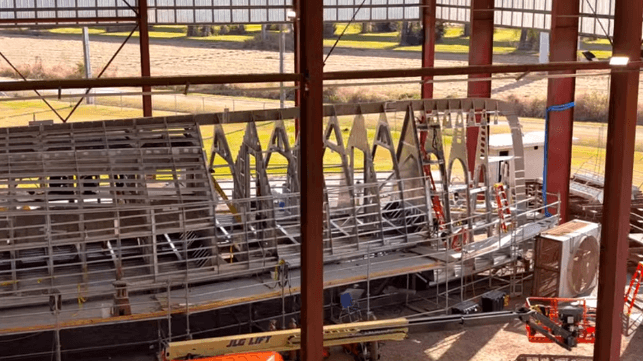

- Change the shipyard's physical plant to speed up production, with expert guidance. An optimized yard layout smooths material movements and workflows, making the most out of available space, capital and labor. This is an area where American yards could tap the experience of high-throughput overseas shipbuilders, says Miska Merikukka, Managing Director for Canada at Finnish engineering consultancy Elomatic.

- Rewrite shipyard order specs to allow equivalent parts for components. This is an administrative change in purchasing, and it happens far from the headlines. Joel Thiesen, VP Sales Global Accounts at leading distributor Wesco, says that simply allowing equivalent parts in the specs would open up competition, bring in new suppliers and radically reduce lead times for scarce items. Time is money in shipbuilding, and even the simplest, most basic missing component can hold up work - but if a yard's engineering and purchasing departments decided to allow substitution, another supplier could deliver the part, ending that time gap.

- Use an unmanned vessel. When there is no crew, the vessel shrinks radically in size and becomes much cheaper to build. It sounds like an option for the far future, but autonomy is already here for survey and defense applications, and is coming soon for others. Vessel-agnostic software companies like GreenRoom Robotics are able to fit autonomous control into hull forms of all kinds, and ABS is working on unified class standards for USV systems. Austal USA, Nichols Bros. and Conrad Shipyard have all won contracts to build unmanned vessels - so for American shipyards, the autonomous option is already a reality. And at least one well-capitalized autonomy firm is aiming its business model squarely at domestic cargo routes (mariners, take note).

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

"This is coming. If you're [moving] dry goods up the Intracoastal, and you're going to do it with an autonomous ship, you're going to drop the bottom out of that route price. Then all of a sudden the industry is going to have to follow, because when you affect the bottom line in the way that autonomy can, it's just inevitable," says Doug Lambert, COO of the vertically-integrated USV builder Saronic Technologies, which owns its own shipyard in Louisiana.

- Most controversial of all: foreign contributions. Adjusting the legal limits on the use of foreign steel forming, hull components, partially-built hulls or even fully foreign-built ships would bring down cost for American owners - but would disrupt a century of tradition and would be unacceptable for many stakeholders. This is the third rail of U.S. maritime policy, but it is now a real-world discussion: certain foreign partners are pushing at the political level to open up the U.S. shipbuilding market to foreign-yard competition, particularly in defense shipbuilding.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.