Flashback: Roosevelt's Man in the Arena

The following words of former U.S President Theodore Roosevelt are engraved in a plaque on display in the Rotunda of the Panama Canal’s Administration Building conveying his personal philosophy and the spirit of his thinking about the achievement of completing the Panama Canal:

It is not the critic who counts, not the man who points out how the strong man stumbled, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena; whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly, who errs and comes short again and again; who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, and spends himself in a worthy cause; who, at the best, knows in the end the triumph of high achievement; and who, at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who know neither victory nor defeat.

Roosevelt is widely given credit for building the Panama Canal even though three presidents’ terms coincided with U.S. Canal construction efforts – Roosevelt, Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson.

Roosevelt saw the canal as indispensable to the U.S. destiny as a global power with supremacy over both its coastal oceans. A timely incident clearly demonstrated this truth to Roosevelt and the world. A naval base had been established in Cuba as a result of the Spanish-American War. The battleship Maine, which was stationed there, was blown up on February 15, 1898, with 260 lives lost. At the time, another battleship, the Oregon had been stationed in San Francisco. To save the day, the Oregon was ordered to proceed at once to the Atlantic, a 12,000-mile course around the Horn. Sixty-seven days later, but fortunately, still in time, the vessel arrived off Florida to join in the Battle of Santiago Bay. The experience clearly showed the military significance of an Isthmian canal.

The Arena

The Isthmus of Panama, only about 50 miles wide at its narrowest point, was characterized by impenetrable jungle, deep swamp, torrential rains, hot sun, debilitating humidity and some of the most geologically complex land formations in the world. Both malaria and yellow fever were endemic to the Isthmus.

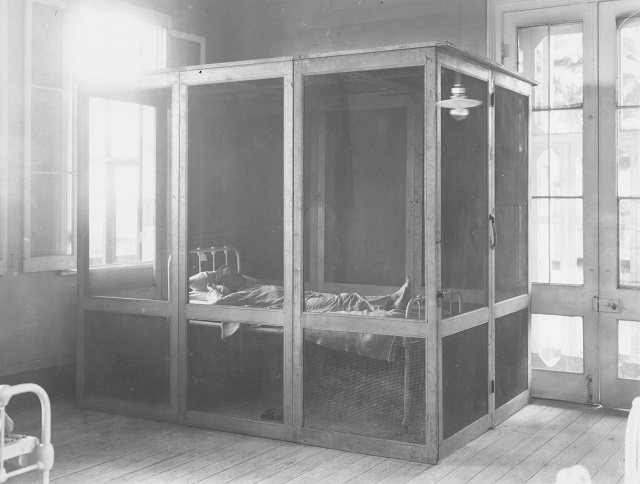

Yellow fever cage

Yellow fever cage

Panama's tropical climate, with a temperature averaging 80 degrees and an annual rainfall of 105 inches, creates ideal conditions for jungle growth similar to that of Brazil's Amazon jungle. The Panama jungle was used as a training ground for U.S. troops sent to Vietnam, as well as for survival training for astronauts going to the moon.

Flooding, especially of the Chagres River, was another very serious problem. Because of the terrain's precipitous slopes, the heavy rainfall gathers quickly into streamlets that flow quickly into the river, causing it to swell at a rapid rate, thus creating floods.

On July 19 and 20, 1903, for example, following two days of heavy rains, the Chagres River (normally some forty feet above sea level at Gamboa) rose to sixty feet above sea level, and its normal discharge rate of 3,000 cubic feet per second had increased to more than 31,000 cubic feet per second.

The French Attempt

The French attempted a canal prior to U.S. involvement and finalized plans for a canal in 1879. Fourteen proposals for sea level canals at Panama were presented before the congress. One, proposed by engineer was Baron Godin de Lépinay, included building dams, one across the Chagres River near its mouth on the Atlantic and another on the Rio Grande near the Pacific. The approximately 80-foot height of the artificial lake thus created would be accessed by locks.

The de Lépinay design contained all of the basic elements ultimately designed into the current Panama Canal. The French would use these concepts as a basis for the lock canal they would eventually adopt in 1887 following the failure of their first sea-level attempt. Had this plan been originally approved, France might well have prevailed in their canal construction effort.

.jpg) Culebra looking north from Point South of Empire (1898)

Culebra looking north from Point South of Empire (1898)

However, French works were abandoned in 1888, and the U.S. purchase of the French-held land for $40 million was authorized by the Spooner Act of June 28, 1902. The beginning of the U.S. canal construction effort dates from May 4, 1904. The U.S. made use of the earlier work achieved by the French and completed the present Panama Canal in 1913.

.jpg) Gatun Dam Looking East from West Wing Wall, Upstream Side (1913)

Gatun Dam Looking East from West Wing Wall, Upstream Side (1913)

The First Transit

The first complete Panama Canal passage by a self-propelled, oceangoing vessel took place on January 7, 1914. The Alexandre La Valley, an old French crane boat that had previously been brought from the Atlantic side now came through the Pacific locks.

Plans were made for a grand celebration to appropriately mark the official opening of the Panama Canal on August 15, 1914. A fleet of international warships was to assemble off Hampton Roads on New Year’s Day 1915, then sail to San Francisco through the Panama Canal, arriving in time for the opening of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, a world’s-fair type celebration.

However, World War I forced cancellation of planned festivities at the Canal. The grand opening was a modest affair with the Canal cement boat Ancon, piloted by Captain John A. Constantine, the Canal’s first pilot, making the first official transit. There were no international dignitaries in attendance.

.jpg) Ancon passing Cucaracha Slide (1914)

Ancon passing Cucaracha Slide (1914)

A Most Expensive Project

The Panama Canal cost Americans around $375,000,000, including the $10,000,000 paid to Panama and the $40,000,000 paid to the French company. It was the single most expensive construction project in United States history to that time. Fortifications cost extra, about $12,000,000.

Unlike any other such project on record, the American canal had cost less in dollars than estimated, with the final figure some $23,000,000 below a 1907 estimate, in spite of landslides and a design change to a wider canal.

.jpg) Culebra cut looking north, steam shovel buried, Las Cascadas (1912)

Culebra cut looking north, steam shovel buried, Las Cascadas (1912)

According to hospital records, 5,609 lives were lost from disease and accidents during the American construction era. Adding the deaths during the French era would likely bring the total deaths to some 25,000 based on one estimate. However, the true number will never be known, since the French only recorded the deaths that occurred in hospital.

.jpg)

Images courtesy of the Panama Canal Authority.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.