South Korea, an Unlikely Polar Pioneer, Hosts Arctic Conference

Over the weekend, as the temperature in Seoul plunged to -12°C, Koreans bundled up in the long puffy black parkas that seem to be this year’s signature winter wear in Asia’s capital of style. In the shopping district of Myeongdong, young people took to the streets to go shopping and enjoy the latest innovations in Korean street food like Oreo churros and egg bread (an entire egg cracked on top of a soft, pillowy oval cake). With the unusually cold weather caused by frigid Arctic air rushing down across Eurasia, Seoul didn’t feel all that far away from the world’s northernmost region, where South Korea is increasingly making its presence felt.

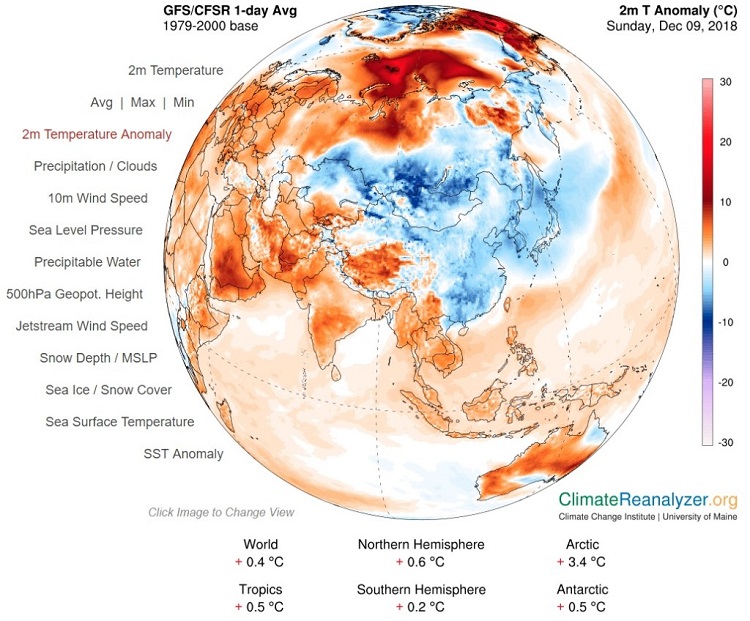

As the Arctic warms, northeast Asian winters may get colder through a phenomenon known as “weather whiplash.” This season, a transfer of energy from an unusually warm Arctic is leading northeast Asia to brace for what may be one of its coldest winters in recent memory. The below temperature anomaly map from the University of Maine illustrates that while the Arctic is unusually warm right now – in some cases up to 20°C hotter than average – the Korean peninsula is 10°C cooler. Under the new normal, countries like Korea, Japan, and China aren’t just researching the Arctic from afar. In winter, these countries may even resemble the Arctic just as the region’s own environment becomes increasingly unrecognizable due in no small part to greenhouse gases originating in Asia.

A temperature anomaly map for December 9, 2018 from the University of Maine’s Climate Reanalyzer.

The bitter cold snap came just in time for the meeting of the first-ever Arctic Circle Forum held in East Asia, which took place over the weekend across the street from bustling Myeongdong in the Lotte Hotel. Approximately 200 delegates, mostly from Asia but with some coming from as far as Canada and Iceland, gathered in South Korea’s capital to learn about the country’s vision for the Arctic. Officials from the two other East Asian countries that are Arctic Council observers, China and Japan, also participated. Notably, Singapore did not send any delegates despite the city-state’s interest in northern affairs and climate change. Throughout the conference, speakers’ faces were broadcast on two enormous screens that felt uncomfortably like the telescreens in 1984, even though the discussions about the Arctic were highly future-oriented.

Ban Ki-Moon rings the climate change alarm bells

Former UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, the first and only recipient of the Arctic Circle’s Arctic Prize, kicked things off on a frosty Friday morning. As delegates gathered in the Lotte Hotel’s opulent Crystal Ballroom, he drew attention to how his successor at the UN, Antonio Guterres, had opened the UN Climate Change Conference (COP 24) in Katowice, Poland just a few days prior with the proclamation, “We are in deep trouble.” Echoing this worry, the South Korean statesmen poignantly recounted his visits to Greenland and Svalbard in 2014: “All the beautiful ice will be melted down, and all the roaring sounds of this ice, just gathered together – it was like the roaring sound of Niagara falls. I was so much surprised and alarmed by all this rapidly changing nature.”

Poetry aside, Ban forcefully underscored: “I spoke out that President Trump’s decision was a political issue… economically irresponsible, and scientifically dead wrong. And he will be standing on the wrong side of history.”

He also pointed directly to Poland’s hypocrisy, which was visible in plain sight at COP24. The Eastern European country’s president, which continues to rely heavily on coal, told delegates, “We have supplies for 200 years, and it would be difficult for us to give up coal — thanks to which we have energy sovereignty.”

Yet the same accusations could be lobbied at the leaders of several Arctic countries and their Asian neighbors, which are trying to combat climate change at the same time as they exploit newly accessible oil and gas reserves. In many ways, then, it was business as usual at the Arctic Circle Korea Forum. Calls for for sustainable development and respect for northern peoples and environments were made at the same time as the latest and greatest in Korean icebreaking LNG tankers was shown off, without anyone much batting an eye. Case in point, the Deputy Ministry for Economic Affairs from Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Yun Kang-hyeon, explained, “The challenges of climate change also ironically present us with some opportunities as a shipbuilder and IT provider.”

South Korea is taking full advantage of those opportunities by winterizing its cutting-edge maritime and telecommunications technologies. Over the conference’s two days, the industrial and technical might of this nation of 51 million people was on full display. Lest anyone be uncertain about what was on offer, Yun closed his speech by stating to the audience: “I urge you to explore the full potential of Korea as an Arctic partner.”

Korean icebreakers combine high-tech propulsion with karaoke machines

A representative from Korea’s Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries described that Korea made its “polar debut” 40 years ago “by catching krill in the Arctic Ocean.” Now, however, the industrial powerhouse is going far beyond fishing. The aptly named Odin Kwon, executive vice president of the Maritime Research Center at Daewoo Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering (DSME), rapidly ran through his company’s impressive achievements in Arctic shipbuilding.

DSME has more than 171 LNG vessels on order as of December 2018, of which several are ice-class tankers. One of the shipbuilder’s most famous recent outputs in this category was Christophe de Margerie, the tanker that carried the first shipment of LNG from Russia’s Yamal project. The tanker is nearly as long as the Eiffel Tower and can carry an amount of LNG equivalent to Korea’s average daily consumption. The vessel is winterized up to -52°C and has 70-mm thick steel plates. The vessel also boasts a 15Mw class Arc7 Azipod system, a propulsion system which enables ships to operate either stern or bow first thanks to the propellers’ ability to turn 360°. As a result, ships equipped with the Arc7 Azipod system can sail through thick ice (here’s a slightly unnerving clip of a ship using the same propulsion system as Christophe de Margerie. China’s forthcoming research icebreaker will also use the same technology).

Despite all this state-of-the-art technology, which has gone into a total of up to 15 LNG tankers DSME is building to service Yamal LNG, Kwon emphasized that construction was “very easy.” So far, 10 tankers have been completed. More studies are going ahead now for how to improve the ships to support Russia’s Arctic LNG II Project, which will take place not far from Yamal LNG.

After Kwon finished his presentation, Kim Jong-deog, Director-General of the Korea Maritime Institute, previewed some potentially groundbreaking innovations that Korean research institutes are pursuing. One is an immediate port facility concept being developed by the Korea Maritime and Ocean University and the Korea Maritime Institute. Researchers are trying to create what would amount to an “instant port” that could accommodate ships of 6,000-92,000 dead weight tons while being capable of generating electricity, desalination, and storing resources like potable water, oil and cereals. Classrooms, a hospital, and small agricultural garden are even being included in the design.

Deploying such a movable facility could be useful in the Arctic. As Michael Perkinson of Guggeinheim Partners, an investment firm, noted, the region still has no deep water port – partly because it doesn’t make financial sense, at least right now, for any specific location. What the Koreans are pitching as a “prompt port facility” that could sail in and sail out on demand might be a solution that wouldn’t saddle any one place with the sizable economic or environmental costs involved in building a permanent port. Think of it as a maritime infrastructure equivalent to “fly in, fly out” labor.

Korea is also pursuing two other maritime innovations. The first is a second research icebreaker to complement Araon, launched nearly a decade ago in 2009. I’m guessing this second ship will also have tasty Korean food, a sauna and a karaoke machine.

The second is a promising ballast-free vessel being designed by Hyundai Mipo Dockyard. When ships discharge ballast water, which they use to enhance vessel stability, sucked up in one ocean into another thousands of miles away, this can introduce invasive species. While international regulations require ships to treat ballast water before discharge, they may not be stringent enough for the Arctic. Although the relatively inconsequential levels of ship traffic to date mean that the number of invasive species in the Arctic is currently low, the region’s general lack of biodiversity compared to more temperate places like the Amazon or Southeast Asia means that its ecology may not be well suited to warding off what will likely be greater threats of invasive species in the future as the number of vessels sailing in the region rises.

Already, Korea has invented the first ballast-free LNG bunkering vessel, an ice-class ship that can sail in the Baltic and North Seas. If such maritime technology could be extended to the LNG tankers sailing the Northern Sea Route to Yamal, this could help safeguard the Arctic’s marine ecosystem.

“Why are the Asian states interested in the Arctic? Go and visit their polar research institutes, and then you will see the scale of their ambitions in the Arctic. It’s truly eye-opening.”

So noted former Icelandic President Olafur Ragnar Grimssón. Following the conclusion of presentations, conference participants did just that.

It was a long drive out to Incheon, where the Korea Polar Research Institute (KOPRI) is located near the country’s main international airport. When we arrived on the clear winter day, the institute’s towering building resembled an iceberg glimmering in the waning sunlight. We walked inside and, while nibbling on complementary Korean biscuits and silver pouches of Capri-Sun (strawberry-kiwi flavored memories of summer camp, anyone?), watched a slick seven-minute video about what Korea is doing “as a nation” to prepare for the “polar age” and the “inevitable race for resources,” as a female voice calmly intoned over videos of crashing icebergs and thundering waterfalls. The video might have been a little bit over-the-top, but the rest of the institute had a certain understated, high-tech elegance redolent of the 1990s sci-fi film Gattaca.

There was a polar library, outside of which hung beautiful glass prints of photographs taken in the Arctic and Antarctic by Korean scientists. The light wooden stairs led down to a lobby with maps of the Arctic and Antarctic laid out in smooth black and gray granite. Across was the entrance to a set of exhibits on the world’s polar regions, including a set of stuffed dead penguins staring forlornly ahead, a mock hull of the Araon icebreaker, and examples of the bright, warm clothing Korean scientists wear in extreme temperatures.

Appropriately for a country trying to raise national awareness about the Arctic (just look at KOPRI’s Facebook page to get an idea of the admittedly very cute PR campaigns they run), several exhibits were geared at public engagement. Visitors could sign a big piece of paper that would be sent to scientists stationed at one of Korea’s three Antarctic or Arctic research stations, stand on top of Araon to have their picture taken, and try out the interactive photo booth, with penguin themes and stickers to the max (I did, but unfortunately never received the email with the photo). In addition, a mock situation room meant as a “tourist attraction” incorporated live feeds from six locations in the polar regions to show visitors how emergencies might be handled.

Finally, we toured the satellite monitoring room. With screens stretching the length of the wall, I felt like we were preparing to either count down for a space shuttle launch or attempt shut down Skynet à la Terminator. Unlike the situation room, this area was not just for show. Korea has become a serious player in the world of satellites. Just a few days ago, the Korea Aerospace Research Institute launched its first fully self-developed geostationary weather satellite from French Guiana. Named Chollian-2A, the satellite joins another Korean endeavor, KOMPSAT-5, up in space. Launched in 2014, the latter is the first satellite equipped with high-resolution synthetic aperture radar, or SAR, which can penetrate clouds to take pictures of the Earth. KOMPSAT-5 can take images twice a day and can help missions related to navigation, ice and snow observation, and search and rescue.

Thus, Korea’s Arctic innovations aren’t just at sea. They’re also in the sky. You can also take them home with you, with each of us visiting KOPRI – an institute that declares it is “opening a better future from the ends of the world” – receiving a build-at-home model Araon icebreaker.

Promoting Arctic cooperation with Indigenous peoples, Japan and China

Korea is working hard to build up its foundations to be an involved player in the Arctic. Korea’s Arctic Ambassador, Park Heung-kyeong, explained, “The Korean government plans to develop domestic institutional foundations and plans to pursue the enactment of legal grounds for cooperation in the Arctic region.” Soon, the Korean government will release its boldly named “Second Arctic Master Plan for 2018-2022,” which will set out the directions for the country’s Arctic policy over the next half-decade.

Despite Korea’s national Arctic ambitions, the country’s representatives were keen to position themselves as partners eager to cooperate in bilateral and multilateral settings rather than attempting everything alone. Early on the conference’s first day, Yun, Korea’s Deputy Minister for Economic Affairs, mentioned cooperation between Arctic states and “non-Arctic states like Korea.” This drew a subtle semantic contrast with how Chinese officials have called their country a “near-Arctic state,” a phrase that makes some northerners bristle.

The Korean government is pursuing Arctic cooperation in two important ways. First, at a people-to-people level, the government provides scholarships to students from the Arctic countries, with priority given to those of Indigenous heritage, to attend the Korea Maritime Institute’s Arctic Academy, held each summer, and the Arctic Partnership Week, which is taking place in the Korean port city of Busan from today through Friday. The Korea Maritime Institute has also partnered with the Aleut International Association (AIA) under the auspices of the Arctic Council to carry out an Indigenous-led mapping project around Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. AIA’s former director, Jim Gamble, emphasized at the Arctic Circle Forum on Friday,

“Indigenous peoples in the Arctic know how to adapt. All we have to do is listen to them.” To at least a certain degree, it seems that Korea has been doing so.

Second, at an international level, Korean officials are promoting the formation of a working group to regularize the efforts of the Trilateral High Level Dialogue on the Arctic, which China, Japan and Korea have convened over each of the past three years. Kim, the Director-General of the Korea Maritime Institute, noted, “We have an annual meeting, but we don’t have any subsidiary body to discuss further cooperation. I think it’s a good idea.” A subsidiary body would help facilitate cooperation between the three countries, all of which have icebreakers and run expeditions each year to the Arctic, in the areas of shipping and shipping regulations, climate and science.

In terms of formal cooperation, the private sector from these three countries may have a leg up on the public sector, as they’re already working together behind the scenes. For instance, the Korean-built ice-class LNG tankers that transported gas from the Yamal LNG Project to China for the first time this summer are jointly owned by Japan’s Mitsui O.S.K and China’s COSCO.

In an accidental but revealing slip of the tongue, Gao Feng, China’s Arctic Ambassador, described Yamal LNG as being located “in Asia, I mean Russia.” It was not a mistake, however, when he declared, “Asia means Arctic.” He added, “The participation of Asian countries in Arctic governance is indispensable,” drawing attention to their involvement in the agreement signed between nine countries and the EU last December to put a 16-year precautionary moratorium on fishing in the Central Arctic Ocean. The fact that the signatories comprised the five Arctic coastal states, the EU, China, Japan and Korea confirms the growing importance of Asian states in polar governance.

Positive reactions to Asian participation in the Arctic, and some skepticism

Even the representative at the Arctic Circle Forum from Greenland, where Chinese investment has elicited negative attention in the Western media, welcomed Asian participation in his country’s development. Jacob Isbosethsen, Greenland’s first representative to Iceland and a former foreign policy minister, expressed, “We are inviting countries from Asia and other places to be a part of this development, because international cooperation is a key part of this.” Subtly referring to the media brouhaha over possible Chinese investment in several Greenlandic airports, Isbosethsen criticized alarmist representations. He argued, “Some medias, some others are putting fear or militarization in place instead of the dialogue that we have. That’s also why we contribute to inviting Asian partners and international partners to Greenland to have a dialogue on a firm basis.”

Marie-Anne Coninsx, European Union Ambassador at Large for the Arctic, noted that the EU welcomes Asian states and appreciates their cooperation, including the regional cooperation that has developed among the three northeast Asia countries. She reminded, “We advocate for more responsible approaches, including a more robust and orderly rules-based approach,” and called for an ambitious, science-based, sustainable and inclusive approach.

On this last point, some in the Arctic might see her inclusivity as going a step too far by extending far south of the Arctic Circle. She described an inclusive approach as meaning “inclusive for the people of the Arctic and inclusive for all those who contribute in addressing the challenges of the Arctic within and outside the Arctic.”

Are the Asian countries doing enough to combat climate change?

Whether the Asian counties are actually doing enough to combat Arctic climate change, however, was the elephant in the room. That is, until one audience member originally from the Russian Arctic pointedly asked, “Asian countries are the biggest contributors ofCO2. What real actions are taken to reduce CO2?

At first, there was radio silence. Then, China’s Arctic Ambassador stepped up and responded, “I’d like to take this question although it was not necessarily addressed to me. Climate change – we all know it’s a fundamental problem for not only the Arctic, but also for the whole planet…Climate change at the end is an economic and technological problem. Only at that level are we able to solve the problem.”

Yet climate change is also an ethical problem. It involves trade-offs between developed and developing countries, between our species and others, between vulnerable frontiers like the Arctic and wealthy cities that can fortify themselves against changing environments, and between our generation and future ones. Stephen Gardiner, a philosopher at the University of Washington, contends that “the more important dimension of climate change may be its intergenerational aspect.” By burning fossil fuels today, humans now benefit at the cost of humans tomorrow, a cycle which repeat itself and leads to climate change’s “seriously tragic structure.”

It may indeed be possible, as China’s Arctic Ambassador noted, to solve climate change through economic measure like determining how to appropriately tax carbon. But such a solution would be tantamount to paying countries to stop from cutting down their forests. It is a bandaid that fails to encourage people to genuinely realize the problem for the future caused by acting out of self-interest in the present.

The sound of climate change, as former UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon described, is deafening. Where ice once stood silently, glaciers now crash down and water rushes steadily. The silence, too, of the developed world – Asian countries among them – as they invent ever more tankers, propellers and platforms to extract Arctic oil and gas at the expense of future generations is deafening, too.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Source: Cryopolitics

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.