Russia's Waning Control of the Caspian Sea

Post-Soviet political geography isn’t working out well for Russia in the Caspian region

The Caspian Sea, the internal sea surrounded by Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Iran and Azerbaijan connected to the Black Sea only via the Volga-Don ship canal, has in history rarely seen open warfare, and has generally been seen as a Russian lake.

But Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has seen tensions surface, brought into focus by recent events. A Ukrainian drone attack on Russian naval vessels docked at Kaspiysk on November 6, which damaged missile ships Tatarstan (F691) and Dagestan (F693), among others. On November 21, a modified RS-26 Rubezh ballistic missile was fired from Astrakhan, the oblast on the northern Caspian shore, and its launch site at Kaspin Yar was immediately counter-attacked by Ukrainian drones. With these incidents placing the Caspian firmly in the Ukrainian war’s theatre of operations, there are broader strategic issues at stake.

The first of these is the use of the Caspian in the shipment of Iranian drones, missiles and ammunition to Russia by ships plying between Amirabadport in Iran and Olaya in Russia’s Astrakhan Oblast. These shipments are delivering munitions that are having decisive effect in the war, giving the Russian a winning advantage. Most notably, a consignment of 220 Fatah-360 ballistic missiles was shipped in September 2024, and Iran has delivered thousands of its Shahed-136 suicide drones.

Large-scale shipments of Iranian-made drones and Russian-compatible artillery ammunition continue, which the Ukrainian attacks are clearly designed to frustrate. Suffering increased barrage damage from Iranian-sourced weaponry, Ukraine is unlikely to give up such attacks, and following precedent may seek novel ways of attacking related targets in the Caspian area.

A second and emerging threat is posed by deteriorating relations between Kazakhstan and Russia. At the St. Petersburg Economic Forum in June, President Tokayev of Kazakhstan, on stage with President Putin, refused to recognize the Russian annexation of Luhansk and Donetsk in Ukraine (and of South Ossetia and Abkhazia in Georgia). He also stated his country would respect Western sanctions on Russia, and he turned down a request to provide Kazakh troops to fight in Ukraine. Temporary ‘technical’ closures of Kazakhstan’s oil export terminal at Novorossiysk thereafter have been attributed to Russian upset with the independent Kazakh position.

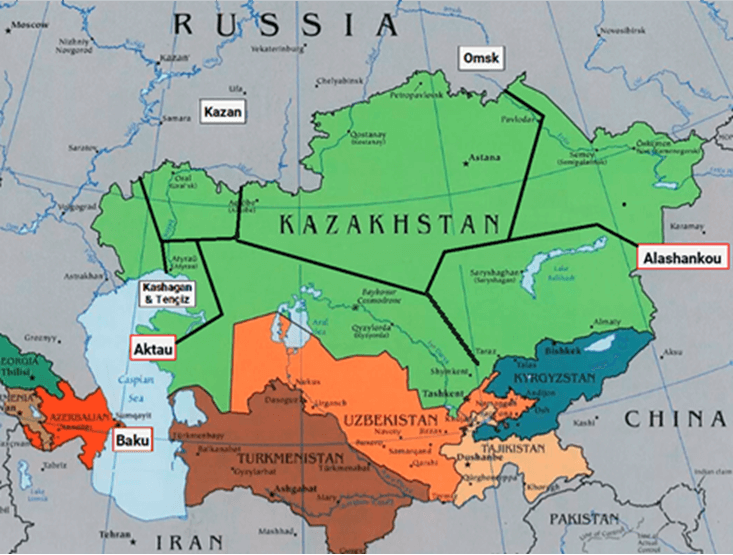

Most of Kazakhstan’s production comes from the Kashagan and Tengiz fields in the northeast Caspian. Exports are primarily dependent on the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) pipeline network, which takes the oil through Russia and terminates at Novorossiysk on the Black Sea. Europe is the destination for 80% of Kazakh oil. The remaining balance is exported to China through the pipeline’s eastern gateway at Alashankou, capacity which the China National Petroleum Corporation does not appear inclined to expand.

Main Kazakh oil pipelines (data from Kazakhstan-China Pipeline LLP)

This adds a third complication: Russia also uses the CPC pipeline network to export its Urals oil from Omsk and Kazan to China. Shippers and traders serving Kazkhstan are fearful of triggering sanctions by using facilities shared with Russia. Russia may want to disrupt Kazakh exports again and to create supply pressures for Kazakhstan’s European customers, but it can only do so by compromising the revenues it earns by using the Kazakh pipeline infrastructure. Such revenues have enabled Russia to maintain its war effort.

Nonetheless, President Tokayev has set in train projects to lessen dependency on Russia by expanding trade on the cross-Caspian Kazakhstan-Baku route, a policy objective synchronized with Azerbaijan.

Built by a joint venture between Emirati and Kazakh parastatals, two shallow draft tankers designed for Caspain operations, the Liwa and the Taraz, have already joined the fleet shuttling between Aktau and Baku, whence Kazakh oil can be loaded in the Mediterranean using the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline.

The capacity increase has contributed to a massive uplift in volumes shipped in 2024, and Kazakhstan hopes to have exported 30% of its oil ouput over this route in 2024, notwithstanding the higher cost of doing so. If a planned trans-Caspian pipeline is built, costs could be reduced and these volumes could rise further.

Other types of cross-Caspian traffic are also increasing, with China keen to develop land corridors to Europe which do not cross Russian territory. To guard against disruption to ship deliveries through the Volga-Don canal and to protectively reinforce the trade route, Azerbaijan intends to build three further tankers, two ferries, and two container ships in newly-established shipyards on the Caspian being set up with Abu Dhabi Ports. Dubai’s DP World is also engaged, having absorbed Topaz, the oil services shipping company dominant in the Caspian, which was previously owned by the Omani royal family.

In light of increased political tensions in the Caspian area, all the littoral countries have been strengthening their naval forces. The Russian Navy’s 28-strong Caspian Flotilla remains the largest, comprising the two Gepard Class frigates damaged in the attack on November 6, plus 16 corvettes and minesweepers. The Iranian Northern Fleet - forming its 4th Naval Region - is led by Moudge Class frigate IRINS Deylaman (F78) with four Sina Class fast attack craft each armed with a 76mm gun and C-802 anti-ship missiles. Both these flotillas are kept busy overseeing traffic between the two countries, which is still largely carried on sea channels rather than by road and rail routes through Azerbaijan. The fleets operated by Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan are smaller numerically and in terms of ship capability, but Azerbaijan notably operates Triton Class midget submarines, the only such craft stationed in the Caspian.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Kazakhstan’s land-locked geography has caused problems in the past - as it seems it will do so again in the future. When Chevron won the ‘Deal of the Century’ in 1993 and took charge of developing the Tengiz oilfield in the northeast Caspian, it discovered it had bought the oil - but not the pipeline needed to export it. The CPC at this time had majority sovereign shareholdings cannily owned by the Sultanate of Oman and the Russian government, interests with huge leverage value that needed to be bought out before the oil could be brought to market[1]. In those days, a trans-Caspian option avoiding Russia was not available.

[1] ‘The Oil and the Glory: The Pursuit of Empire and Glory on the Caspian Sea’, Steve LeVine (Random House October 2007)

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.