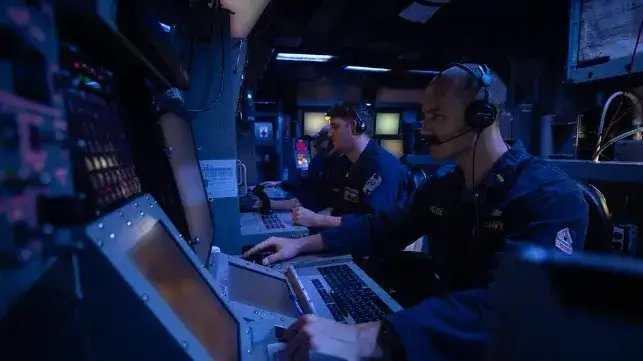

Op-Ed: US Navy's Networks Aren't Ready for a Contested Comms Environment

Recent acquisitions have focused on bandwidth-heavy, compute-intensive, headquarters-focused systems that are doomed to fail in contested communication environments

[By Nicholas A. Kristof]

In his remarks at his assumption of office ceremony, Admiral Caudle stated that, “Great power competition is sharpening, threats and capabilities are proliferating, technological disruption is accelerating, the maritime domain is increasingly contested and the margin for error is shrinking. To prevail in this environment, we must build and sustain a Navy that is resilient, agile, globally present, and credible in combat.”

To accomplish this, the Navy must ruthlessly pursue two seemingly disparate capabilities – technical interoperability and the capability to operate in contested communications environments. The need for interoperability in naval operations has never been more critical. However, these operations will increasingly be forced to occur in contested communication environments, where data access and connectivity cannot be guaranteed. Balancing these two imperatives—interoperability and resilience in contested conditions—will be vital to successful maritime operations.

Interoperability enables coalition and joint forces to share information, coordinate actions, and execute missions with speed and precision. In a security environment where no single nation can address threats alone, it allows navies from different countries to communicate and share situational awareness and use common data standards and communication protocols. It also allows forces to integrate sensors and weapons systems for combined lethality and efficiency. Naval operations today—conducted with NATO partners, regional partnerships, or ad-hoc coalitions—depend on interoperability for command and control, intelligence sharing, and battle management.

Despite advances in networking and communications, contested conditions remain a harsh reality. Adversaries will employ electronic warfare, cyberattacks, and other anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) strategies to disrupt communications and links. Operating effectively in these conditions requires resilient systems that degrade gracefully, continue core functions autonomously, and then reconstitute automatically. It also requires bandwidth efficient communications protocols that send only the minimum number of bits required to accomplish the mission. Forces also need data prioritization and edge processing, enabling platforms to process and act on information locally when disconnected from the network.

Systems that possess these capabilities exist today. But these principles have not served as first-order design considerations for many systems, and the Navy acquisition enterprise is not well-organized to test novel solutions from industry.

The challenge is to design and field systems that support improved interoperability yet can still remain effective in communications-degraded environments. This demands modular, open architectures that allow systems to plug and play across nations while still functioning independently when disconnected. It also requires distributed C2 models to ensure that no single point of failure can collapse operational effectiveness. Zero-trust cybersecurity frameworks will help maintain data integrity even when network control is lost.

Despite “interoperability” being a buzzword for years, the Navy and Marine Corps team, and the wider Joint force, has been extremely slow to improve. Stovepiped acquisitions, lip service instead of ruthless prioritization, and institutional inertia all stand in the way of much-needed change. Worse still, recent acquisitions have focused on bandwidth-heavy, compute-intensive, headquarters-focused systems that are doomed to fail in contested communication environments and leave commanders blind and unable to communicate with their forces. In some of these cases, Navy leadership has been won over by fancy and buzzworthy pitches for capabilities that do not actually operate as marketed.

Admiral Caudle must provide forceful and clear direction to the naval acquisition enterprise that he ultimately oversees. That enterprise must prioritize systems that maximize interoperability when conditions permit, and the ability to operate alone and unafraid when necessary.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Nicholas A. Kristof is a 1996 graduate of the United States Naval Academy and a retired submarine officer. The views expressed are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the official views of any organization with which he is affiliated.

This article appears courtesy of CIMSEC and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.