Is the U.S. Really Committed to an Indo-Pacific Trade Agreement?

[By David Uren]

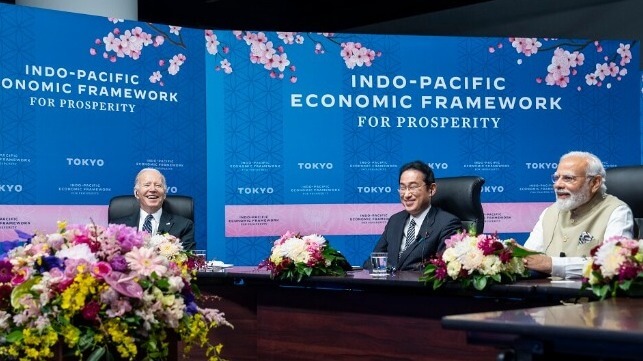

The Biden administration attracted a dozen nations to the launch of its Indo-Pacific Economic Framework but the lack of commitment to the plan from either the United States or the region suggests it’s unlikely to have much impact.

The framework is intended to balance the US security interests in the region with a more structured economic relationship. After former president Donald Trump pulled out of the US’s own creation, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the US has been sidelined as nations in the region struck far-reaching trade deals without it. The US strategy for dealing with the emerging Chinese regional dominance has been characterized as "all guns and no butter."

China has been a clear winner, joining the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and applying to join both the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the innovative Singaporean initiative, the Digital Economic Partnership Agreement (DEPA).

While the launch statement was signed by the seven leading ASEAN nations as well as India, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand and the US, last-minute wrangling over the language, which seeped into the public domain, highlighted the tenuous nature of the collective.

According to the Financial Times, the US draft wanted to declare the "launch of negotiations." Instead, it merely announced that "we launch collective discussions toward future negotiations." It is an agreement to talk about talking. It hasn’t been disclosed who was most reluctant, but it could have been India.

On the US side, the lack of commitment is evident in the apparent decision to implement the agreement by executive decree, rather than attempting to legislate it through Congress. US Trade Representative Katherine Tai says the IPEF design drew "a very, very strong lesson" from the failure of the TPP. She said it would be important to keep Congress "close" to the IPEF process but she would not commit to seeking its approval.

As nations across the region are only too well aware, executive decisions in the US can be overturned in an instant by the next administration.

When the Obama administration was negotiating the TPP, there were difficult compromises made by all parties to meet the US demands for increased intellectual property and copyright protection, opening services and agricultural markets, and independently arbitrated dispute settlement.

The essence of a trade agreement is that nations agree to supress domestic protectionist forces in the interests of advancing their internationally competitive industries.

Without a legislated market commitment from the United States, governments in the region cannot be expected to accept the political costs inherent in meaningful reforms, particularly because the US is offering nothing in return.

Because the Biden administration cannot get trade deals through congress, IPEF provides no improved access to the US market. There are no tariff concessions on offer.

Tai sought to make a virtue of this shortcoming. She argues that tariff deals are old fashioned. She says the average tariff for favored nations in the US is only 2.4 percent, so access to US markets is not a problem. "We’re offering a program relating to connectivity for our stakeholders. And that goes beyond tariffs."

While it’s true that US tariffs are low, this is not the case for many of the prospective members of IPEF. Malaysia’s average tariff is 21 percent, India’s is 17.1 percent, South Korea’s is 16.5 percent and even free-trading Singapore’s is 9.5 percent.

Both the CPTPP and RCEP offer reciprocal tariff cuts to their members and this favours intra-regional trade which includes China, as a member of RCEP but not the US (or India). Trade from US multinational subsidiaries in member nations can still benefit from these trade deals, but not exports from the US.

US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan argues that "the fact that this is not a traditional free-trade agreement is a feature of IPEF, not a bug."

The framework is a novel approach to trade regulation, inviting members to negotiate on trade standards, decarbonization, supply chain management and compliance with tax, anti-bribery and anti-money-laundering requirements.

Members can seek a binding agreement in any or all of these four areas. Traditional trade deals require all members to agree to all elements. A member seeking a binding agreement in one of the four "pillars" would still have to agree to all components of it. There is to be no enforcement mechanism, although members defaulting on commitments would not be entitled to the scheme’s benefits.

Sullivan says the incentive for members to negotiate would be "the opportunity to work closely with the US on rules and standards….The US is going to be a partner of choice on all of the elements of this framework, even setting aside the question of traditional tariff liberalization."

While this may be true, it still begs the question of what political costs members will be prepared to carry, particularly when the US is emphatic that it will bear none.

For example, the ‘fact sheet’ released by the White House emphasizes the importance of high standards for the digital economy, particularly cross-border data flows and data localization. Both are bugbears for US tech companies, particularly in China. However, there is reluctance in other Asian economies about giving the US tech companies carte blanche to deal with the personal data of their citizens. Even in Australia, there is concern about foreign ownership of data.

The fact sheet emphasized strong standards for labour, the environment and corporate accountability that would "promote a race to the top for workers through trade." However, US standards on these issues are radically different from those in prospective members such as Vietnam, India or the Philippines.

The sketchy documentation that has been released includes some intriguing possibilities. It talks about establishing an ‘early warning system’ for supply chain disruptions, mapping "critical mineral supply chains" and tackling the "discriminatory and unethical use of artificial intelligence." It is not clear just what these would involve. Although not in the documentation, US officials have also spoken about investment in regional infrastructure.

The US expects that the discussions about negotiations would be followed by a ministerial summit in the September quarter which would launch negotiations, with countries nominating which of the four "pillars" of the framework they wish to engage. The aim would be to reach final agreements within 12 to 18 months. Some parts could start sooner than others.

At least some of the initial 12 regional nations will go along with some of what the US is proposing, but the lack of a US legal mandate for the agreement means other members are unlikely to invest political capital in it. On top of this, the IPEF is also unlikely to constrain the choices member nations make in their dealings with China.

David Uren is a senior fellow at ASPI. This article appears courtesy of The Strategist and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.