Is the Canadian Arctic More Secure Now?

Although there is no perceived military threat to the Canadian Arctic at the moment, a number of sovereignty issues have yet to be resolved: the maritime boundary in the Lincoln Sea between Denmark and Canada, Hans Island, the Alaska-Yukon border extension into the ocean, the extension of continental shelves, and more importantly, the recognition of the strait baseline method to define the internal waters of Canada in the Arctic. The latter affects the status of the Northwest Passage. The government must make sure that it exercises its full sovereignty over these waters. That requires the ability to monitor increasing human activities on and below the surface and to enforce our regulations and laws.

Strong Secure Engaged, Canada’s Defence Policy of 2017 clearly highlights the Arctic as a sector of priority. The word Arctic appears 77 times in the document. The policy provides the cornerstone document that will guide the Canadian Forces’ efforts to monitor the Canadian Arctic and act as required.

2017 was the second warmest year on record. The ice in the Canadian Arctic was also at its second-lowest point since satellite tracking began in the 1970s. The shipping season in the Arctic is getting longer and is allowing greater and easier access throughout the Arctic Archipelago. During the summer of 2017, over 178 ships made more than 400 trips in the Arctic.

There are more mineral exploration and exploitation taking place now that access all year around is made easier. The Baffinland Iron Mines Corporation’s Mary River mine on Baffin Island is a prime example. In 2017, 55 trips of bulk carriers shipped over four million tons of iron ore from the northern tip of Baffin Island to Europe.

Arctic tourism is becoming more popular. Several cruise ship companies are in the process of building an additional 22 ice-capable cruise ships. Silversea Cruises Ltd is even planning an Arctic circumpolar voyage for 2019.

The number of polar flights over the Arctic has also increased. These are flights that connect New York to New Delhi directly over the North Pole for example. Those flights are possible today because aircraft have longer legs and Russia has opened its airspace to commercial traffic. Although the airlines find these routes more convenient and economical, they represent both a risk and a responsibility in terms of air traffic management and search and rescue. Canada did commit to improving its capability to execute search and rescue missions under the Arctic Council’s Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic.

Present strategic assets

In 2000, Canadian Forces Northern Area (CFNA), the precursor of Joint Task Force North (JTFN), raised the alarm about the future security impact of global warming and the increasing access to transportation routes and natural resources at a time when the limited Canadian Forces assets were being reduced.

Much has changed since then, and there is more change on the way. First, let us review the major strategic assets that the Canadian government presently has to meet its sovereignty responsibilities in terms of security. These assets are not limited to those of the Canadian Forces.

The Canadian Forces has improved its ability to better monitor activities in the Arctic through its headquarters based in Yellowknife. The JTFN headquarters is responsible for the coordination of many military activities in the Arctic. Headquarter detachments in Whitehorse and Iqaluit, the Area Support Unit (North), the reserve company of the Loyal Edmonton Regiment in Yellowknife, the 1st Canadian Ranger Patrol Group and 440 Squadron provide JTFN a permanent physical presence in the Arctic. The Arctic Security Working Group, which was formed in 2000 by CFNA, continues to provide an excellent vehicle to share information and coordinate some of the efforts of the federal departments in the true fashion of the “whole of government” approach, which is essential in the Arctic given the cost of operation and the paucity of federal infrastructure.

Over the years, the JTFN headquarters has seen a solid growth in its ability to monitor activities in its area of responsibility, coordinate operations and support training of southern units such as the Army’s Arctic Response Company Groups. Through various annual exercises under the umbrella of Operation NANOOK, JTFN maintains its planning and command and control capabilities, while at the same time contributing to the federal government’s presence throughout the Arctic Archipelago.

There is also the Canadian Armed Forces Arctic Training Centre in Resolute Bay that provides a good support base for operations in the High Arctic, the Canadian Forces Station Alert which provides weather data and signals intelligence, and the North Warning System which provides alert to the Canadian Air Defence Sector and forms part of NORAD. There are three Forward Operation Locations (FOL) for the CF-18 in Yellowknife, Inuvik and Iqaluit. These FOLs support air defense operations by CF-18 based in Canadian Forces bases Cold Lake and Bagotville.

In a significant decision reinforcing our sovereignty, the Royal Canadian Air Force has recently modified the Canadian Air Defence Sector Identification Zone to include that portion of the Arctic Archipelago above the line of radars of the North Warning System. Until now, the northern tip of the Arctic Archipelago had received little attention in terms of monitoring air activity north of the North Warning System. Our capability to monitor such activity is still limited, but this is about to change through the modernization of the North Warning System.

MacDonald Dettwiler and Associates Ltd. (MDA) RADARSAT 2 provides a reasonable capability to monitor maritime activity. It’s synthetic aperture radar, day and night, and through cloud capabilities make it a powerful system. The data it provides, when cross-referenced with the information provided using space-based Automatic Identification System, the Northern Canada Vessel Traffic Services (NORDREG) and other sources, assists with the identification of targets of interest.

Access to ship Automatic Identification System (AIS) data from commercial suppliers such as exactEarth and ORBCOMM allows the government departments to tap into this resource. The AIS requires certain categories of ships to transmit data such as speed and direction to improve marine safety. Those signals can be picked up from space and provide a degree of maritime situational awareness. This is especially useful in the Arctic. The fleet of CP-140 Aurora aircraft, with their upgraded sensors and mission systems, provides another layer of maritime surveillance when deployed to the Arctic.

The establishment of the Canadian High Arctic Research Station (CHARS) in Cambridge Bay furthers the federal presence in the Arctic and will provide better science to guide stewardship decisions in the Arctic. It will complement the operations of the Polar Continental Shelf Project operated by Environment Canada in Resolute Bay. In Eureka, there is a Natural Resources Canada weather station as well as a Canadian Forces support facility for the maintenance of the High Arctic Data Communications System on Ellesmere Island.

The new road from Inuvik to Tuktoyaktuk will allow supplies, equipment, and personnel to be moved by road all the way to the Arctic Ocean in case of an emergency. It provides one more option for federal agencies to deploy assets and resources to the western Arctic.

There is a new fiber optic communication line to Inuvik. It allows a high capacity communication link to the south. It provides the RCAF FOL in Inuvik with access to high-speed internet connection. It has also allowed greater support to the Inuvik satellite antenna farm supporting federal government services, as well as other international operations.

There are a number of airports and airfields throughout the Arctic to support operations. However, many of those are small and made of gravel.

The present assets provide a limited capability to deal with security situations or emergencies.

Approved future assets

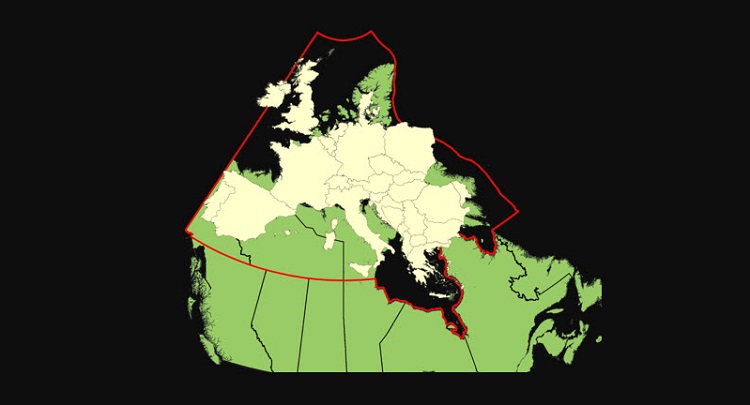

Although the present assets are important, one must take into consideration the fact that the Canadian Arctic is immense (as shown on the following map).

Continental Europe over the Arctic (Image: Taken from CFNA presentation)

Most Canadians are unaware that the center of mass of Canada is actually in the Arctic near the Nunavut community of Baker Lake.

The MDA RADARSAT Constellation Mission, led by the Canadian Space Agency, will eventually replace RADARSAT 2. The satellites’ launch is planned for November 2018. This set of three modern satellites should ensure data continuity, reliability and enhanced operational use of their all-weather synthetic aperture radars. The Constellation will provide daily revisits of Canada’s Arctic. It will provide a high-resolution capability of 3 meters in the spot mode.

The Arctic and Offshore Patrol Ship (AOPS) project, which is under construction now, will shortly deliver the first of five ice-capable ships, with an option for a sixth ship. The ships are designated as the Harry DeWolf Class. These ships, with a capability to deal with new-year ice of up to one meter, will be able to increase the federal government’s presence as well as improve its situational awareness in the Arctic during the active shipping season. They will vastly increase the capability of the government to deal with search and rescue, scientific research and support to other federal government departments in the Arctic. They will provide outstanding platforms to manage a crisis in their arctic area of operation.

Canada is looking at acquiring three icebreakers and converting them for their ice-breaking needs, which will improve the Canadian Coast Guard’s ability to maintain its presence in the Arctic Archipelago. The red and white ships with the large maple leaf on their sides are the most visible federal presence from a sovereignty point of view up to now. The Canadian Coast Guard has also established a number of Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary stations in the Arctic which will improve Canada’s ability to do marine search and rescue as committed under the Arctic Council’s Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic. The Inuvik Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary is receiving two search and rescue Sea-Doos.

Under the Ocean Protection Plan, the federal government will be seen to be better governing the Arctic Ocean in line with its sovereign responsibility. Transport Canada and the Canadian Coast Guard are developing a series of shipping corridors through the Arctic. Such corridors, if made compulsory, would minimize the risks to marine life and the Inuit communities. They would also allow the concentration of limited resources, such as mapping of the seabed for safer navigation, in this vast area. In April 2016, the Pew Charitable Trusts produced a report titled “The Integrated Arctic Corridors Framework: planning for responsible shipping in Canada’s Arctic waters”. It produced a number of charts that suggested corridors to minimize such impacts.

A new port in Iqaluit will begin construction in July 2018, and it should be completed by November 2019. It will be the first and only port in the Canadian Arctic. This asset will augment the federal capabilities significantly. The port of Churchill in Manitoba is not located in the Arctic and, at the moment, is lacking a reliable rail line with the south. The Canadian Forces are in the process of finalizing the development of a refueling capability at Nanisivik.

Future potential systems

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF)’s Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS) project, formerly known as the Joint Unmanned Surveillance and Target Acquisition System (JUSTAS) project, has moved into the options analysis phase. That system would bring a cost-effective way to patrol the vast expanses of the Arctic and provide another layer of surveillance capability to add to the other systems in place.

Communications in the Arctic have been a significant challenge over the years. This is mainly due to the lack of land base connectivity through fiber optics or microwave links. Communications to support military operations and the Canadian Coast Guard have traditionally been provided through geostationary satellite links, which are expensive. As one progresses further north, communications through those links with geostationary satellites become increasingly unreliable. Other satellite communications providers like Inmarsat or Iridium do not have the high bandwidth capabilities required by modern networks and sensors.

But this is about to change when Telesat, a Canadian company headquartered in Ottawa, completes the development of a constellation of 100+ low-earth-orbit satellites with an in-service date of 2022. “The global network will deliver fiber quality throughput (Gbps links; low latency) anywhere on earth.” In addition to providing better communications anywhere in the Arctic to support security operations, the control of the system will be in Canadian hands, and it will provide a degree of communication redundancy through the large number of satellites. Geostationary satellites are vulnerable to various forms of attack. They would likely be targeted early in a conflict. The Canadian Forces Enhanced Satellite Communications Project – Polar (ESCP-P) has just completed its Request for Information (RFI). It has an in-service date in the 2028-2029 timeframe.

The Qikiqtaaluk Corporation is hoping to build a port in Qikiqtarjuaq. This addition would augment the facilities that can be used for refueling, repairs, search and rescue and dealing with an environmental emergency in the eastern part of the Arctic.

The proper monitoring of underwater activities has long been a gap in our all domain situational awareness. As far back as the 1987 White Paper on Defence, there have been efforts to deploy sensors to monitor submarine activity in the Arctic. Recent efforts were done under the Northern Watch Technology Demonstration Project run by Defence Research and Development Canada (DRDC). For a number of years, various combinations of systems which included surface radar and remote weather monitoring were tested at the Gascoyne Inlet of Nunavut. That project ended in 2016. In 2015, a new program was stood up: the All Domain Situational Awareness Science & Technology Program with funding over $100 million. The program counts several initiatives to explore various elements of surveillance technologies and knowledge required to monitor sub-surface activity like autonomous underwater vehicles with towed arrays and the investigation of how sound propagates through Arctic waters.

Options for the replacement of the North Warning System are now being explored. The present line of radars which was installed in the late 1980s is largely obsolete, especially when considering Russian supersonic cruise missiles. There is presently a Request for Proposal for the installation of a polar over-the-horizon radar somewhere in the High Arctic. It is probably one of the various options being considered by NORAD to improve long-range detection of threats.

The Coast Guard fleet of icebreakers is 39-years old on average, and ships are reaching the end of their design life. Although there is a refurbishment and life extension program in place and the recently announced intention to purchase three modified icebreakers, there is a need for a fully funded program to replace those vessels. We are aware that there is a plan for the replacement of the CCG Louis St-Laurent with the CCG Diefenbaker, but this ship will only likely see service in 2023, and the plan for the replacement of the rest of the fleet is not entirely clear. “At this time, with the exception of the new polar icebreaker CCGS John G. Diefenbaker, no new building plans have been approved for the replacement of these icebreakers.”

In 2000, I recommended the deployment of high-frequency surface wave radars (HFSWR) to monitor the approaches to the choke points in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. We need to know what is coming into our waters before they reach them. Such a system was developed and deployed by the Department of National Defence to monitor Canada’s East coast in 2003. It can monitor maritime traffic to long distances depending on conditions. In 2011, Defence Research and Development Canada (DRDC) contracted for the development of a 3rd generation HFSWR capable of operating 24/7 without causing interference to other users. This system was tested in Nova Scotia in 2013. It is my understanding that DRDC is exploring the possibility of such a system in the Arctic.

The Army for its part has a project to improve its mobility in the Arctic. The Domestic Arctic Mobility Enhancement project will be a combination of tracked, articulated and amphibious all-terrain carriers, as well as snowmobiles and all-terrain vehicles for tactical and operational mobility and to support logistical resupply.

It is fine to have multiple layers of surveillance in the Arctic, but there is also a need for a capability for opposed boarding of ships in the Arctic. Given the increase in maritime traffic, it is only a matter of time before an unscrupulous player enters the Arctic Archipelago or does something in our exclusive economic zone that requires the ability to do an opposed boarding of that ship. The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) has a great deal of experience in doing such boarding given their experience in the Persian Gulf. However, until the AOPS are fully deployed, doing the same in the Arctic will be more challenging given the vast distances involved, weather and the lack of infrastructure.

A Canadian Forces boarding party or Royal Canadian Mounted Police assigned to a Marine Security Emergency Response Team and their equipment would have to be flown to the airfield closest to the offender. From there the team would have to sail some distance to the ship in uncertain weather. It is a capability that needs to be planned for and exercised.

A demonstration of this capability took place during one of the summer Arctic visits of Prime Minister Harper. That demonstration was planned months in advance and the required assets were prepositioned ahead of time. What is required is a capability that can be deployed at 24 hours’ notice. That capability would need to be exercised at least yearly. It could be done under the umbrella of the NANOOK series of exercises.

A paved runway in Resolute Bay to support RCAF surveillance and operations and the mandate of various federal departments would go a long way to increase the capabilities of the federal government, as Resolute is central to the Arctic Archipelago and sits squarely on the Northwest Passage. A port in Resolute Bay would be a tremendous strategic asset that would support Coast Guard and Royal Canadian Navy operations in the Arctic.

Although the Canadian Forces will receive new fixed-wing search and rescue aircraft, none of them will be based in the Arctic. Their slower speed compared to the present CC-130 means longer response times in the Arctic where time is usually critical. Deploying some in the Arctic would make them more responsive.

Only ships of 300 tons and above are required by regulations to report on NORDREG. Reducing the threshold to 30 tons would increase the maritime situational awareness.

Conclusion

Although more is being added to the present capabilities and even more could be done, the security of the Canadian Arctic has improved over the last few years and will continue to do so for some years to come as more and more strategic assets become operational to cope with the disappearing ice and increasing levels of human activities.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Colonel (Retired) Pierre Leblanc is a former Commander of the Canadian Forces in the Canadian Arctic. www.arcticsecurity.ca

Reprinted with permission, Vanguard August/September 2018

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.