How the Suez Canal Came to Be

For a little over a week the world’s attention zeroed in on the Suez Canal, an artificial channel connecting the Mediterranean and the Red seas across Egyptian territory. The canal offers the shortest sea route between Europe and Asia, funneling around 10 percent of global trade. And so it made the headlines when a massive container ship, “Ever Given”, became wedged diagonally across the canal, creating a huge, expensive backlog of other vessels.

I am a social and cultural historian who has studied the region and the people who live there. While the economic benefits of the canal are readily apparent, its history of technical mishaps and failed ambitions is mostly buried.

The idea for a canal between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea was a long time in the making. The ancients must have talked about it. And Napoleon Bonaparte, who invaded Egypt in 1798, dreamed about it. Eventually, it was a French diplomat, Ferdinand de Lesseps, who vehemently promoted the scheme and was given permission to start working on it in 1854.

In 1858 La Compagnie Universelle du Canal Maritime de Suez (Universal Company of the Maritime Suez Canal) was formed with the authority to cut a canal. The company was under the joint auspices of the Egyptian government and the French Canal Company.

Prior to the mid-19th century, the Isthmus of Suez – the 125-kilometer strip of land that lies between the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea – was a quiet spot. It was a hard and pebbly undulating plain intersected by ranges of hills. It was traversed by nomadic Bedouins and peripherally settled by a few fishermen.

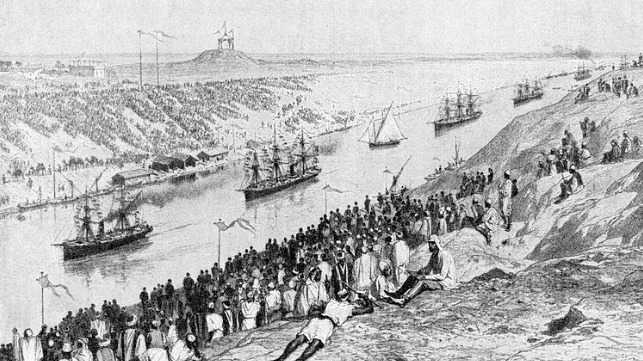

In April 1859, works under the company began cleaving the isthmus in a north-south direction. In the following decades, this desert-like region experienced a dramatic transformation as a string of construction sites popped up. People poured in, bringing with them earth-moving equipment and livestock.

Work begins

Work on the canal kicked off in 1859. Components of locomotives, barges and dredgers, among other equipment, began streaming in from Europe. Most went to the northernmost canal worksite at Port Said, where they were assembled.

The excavation of the channel proceeded southwards. As the digging took strides, supplies were transported farther, using land and water, into the isthmus. Along the new waterway, where scarcely a blade of grass was previously found, vegetation began to spring up. From about 1861, there was also an influx of working animals including donkeys, horses and camels.

The company vied tirelessly for control over settlements and workers. It had a system of forced labor and started to conscript thousands of Egyptian workers in 1862. The workers, theoretically paid and fed by the Egyptian government, came from both the north and south of Egypt. They toiled alongside “free” workers, including Arabs and Europeans.

The forced labour of Egyptians formally ended in 1864 when a new ruler – Isma'il Pasha – took over and eliminated the practice. This act stalled the project and forced the company to introduce more machinery and lure more foreign workers through enlistment campaigns.

Canal labourers came from all over the Mediterranean basin, North Africa and the rest of the Ottoman Empire. Some came from as far away as the British Isles. These labourers worked in the company’s payrolls, offered services to workers, and lived off expedients such as thieving, contraband and prostitution.

The cities that would outlive the comings and goings of this particularly transient population were Port Said (founded in 1859 on the northern Mediterranean shore), Ismailia (originating in a worksite in the middle of the isthmus that dated back to at least 1860), and Port Tewfiq (founded in 1867) facing the centuries-old Red Sea harbour town of Suez.

These cities still derive some of their economy from the canal. For instance, to this day, 9,000 workers toil in ship repairs and other maritime services for the seven subsidiary companies of the Suez Canal Authority in Suez, Ismailia and Port Said. But today there is a lot more to the local economy than the canal.

A rocky start

During the canal’s early days, life in these cities had its challenges. This was partly because of uneven infrastructural development. For instance, homes and sewers in the “Arab” quarters of Port Said and Ismailia were vulnerable to natural calamities, more so than those in “European” areas.

The canal, as a whole, was a haphazard project right until the end. My research in scattered archives found that just 10 days before the canal’s official inauguration date – on November 16, 1869 – 14 dredgers were still operating. They were meant to prepare the passage for festive vessels to pass through the first section near Port Said. But rocks were still being found along the waterbed and explosives were placed to set them off. Strong transverse winds, curves, sands and opposing currents also raised concerns for the ships trying to make it through.

What the canal brought in its wake

The canal changed global trade in dramatic ways. It brings $5 billion to Egyptian coffers each year, although it is unclear who exactly benefits from that boon.

It had geopolitical implications beyond the movement of goods. The canal cities experienced bombing and siege when British, French and Israeli forces attacked the canal in 1956, after Gamal Abdel Nasser proclaimed its nationalization.

The canal also precipitated seismic shifts in the composition of sea life. The opposite streams – one from the Mediterranean and the other from the Red Sea – merged some time in 1866. This allowed for the migration of different marine species along the waterway and the movement of numerous invading species – from water molluscs to cholera bacteria. This resulted in a pattern of invasions with long-term and large-scale damage to ecosystems.

For instance, Red Sea species – including fishes, crabs and prawns – successfully made their way up north. The pearl-oyster, previously unknown in the Mediterranean, became abundant on the northern coast of Egypt and reached as far as Tunisia’s coasts.

The Suez Canal’s history has been forged over a century by multiple entities and people. Despite its huge influence on the global scene today, its past has been marked by colossal stumbling blocks and wild dreams which, since its inception, re-directed the course of its story.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Lucia Carminati is an assistant professor at Texas Tech. She is a social and cultural historian of the modern Middle East, with a particular focus on nineteenth and early-twentieth-century Egypt.

This story appears courtesy of The Conversation and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.