China's Navy is Using Quantity to Build Quality

[By Matthew Hipple]

The United States Navy holds up quality as the firebreak against the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) dominant fleet size and overwhelming industrial capacity. But the development and maintenance of professional skills to fight wars, build ships, and maintain fleets requires material, time, and people – in a word, quantity, for which the PLAN holds the undeniable advantage.

The cliché that “quantity has a quality all its own” improperly frames the advantages conferred upon America’s PLAN adversary by the size of its navy and its various supporting enterprises. Quantity is not merely an attribute with which to bury one’s opponent; quantity pragmatically applied provides individuals and entire professional classes the opportunity to cultivate and cement quality. Without the opportunity afforded by scale, the U.S. Navy will fall behind an adversary with a world of opportunity to explore new skills, new systems, and grow its force-wide professionalism. The potential qualitative impact of quantity shows at every level – from the shipyards to fleet training for individual sailors.

The Maritime Industry and a Nation’s Maritime Character

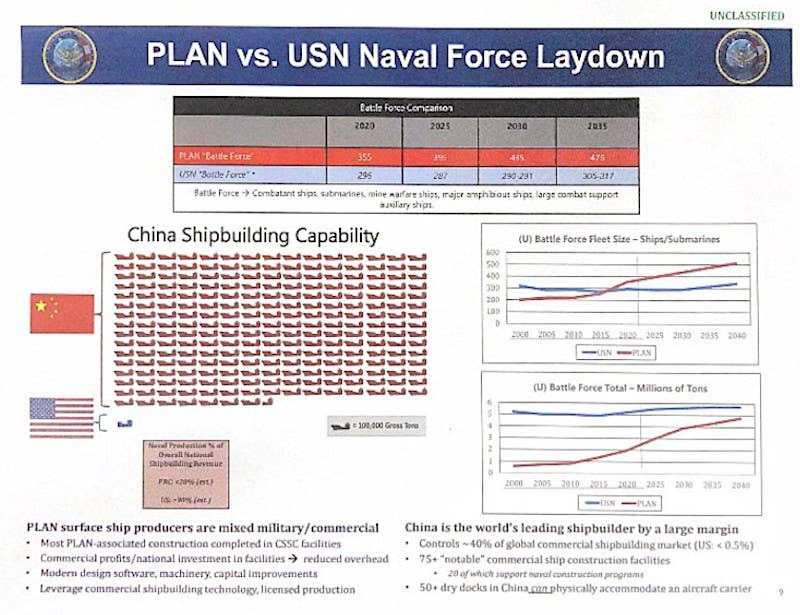

The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) recently assessed that the China’s shipbuilding industry fields 232 times the shipbuilding capacity of the United States, representing almost 50% of total global shipbuilding capacity. To stark quantitative differences like these, the U.S. Navy responds, “in many ways our shipbuilders are better shipbuilders, that’s why we have a more modern, more capable, more lethal Navy.”

An unclassified slide from the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) highlighting differences between U.S. Navy and PLA Navy shipbuilding capacity, ship count, and overall tonnage. (U.S. Navy graphic)

Unfortunately, these snapshots of quantitative position fail to account for the rate of qualitative improvement required for China to achieve this feat of material and professional development – from backwater to backbone.

China’s modern shipbuilding behemoth is only 20 years old, the result of a deliberate Chinese Communist Party (CCP) campaign of maritime expansion begun in response to the US Navy’s Summer Pulse 2004 exercise when China represented only around 10% of global ship production. In the time between LCS program initiation in 2004 and the final mission package reaching initial operating capability in 2023, the CCP revolutionized an entire industry and supporting professional class. Meanwhile, 20 years of mismanaged shipbuilding plans – have left American shipbuilders without the demand needed to sustain itself, its professional community, or meet naval demand.

John Konrad of GCaptain estimates that making “an American shipyard professional takes about 3-5 years.” Although the communal professional improvement of China’s shipyard workers will take longer due to their extreme individual specialization compared to more broadly skilled Western shipyard workers – the China’s shipbuilding cadre have that opportunity to improve with the scale of their enterprise. And ultimately, specialized workers who exist are superior to theoretically higher quality generalists who do not.

But shipbuilding is just a piece of that qualitative puzzle solved by the scale of China’s maritime industry. There is a maritime quality to China’s population that America has left behind. As Mahan notes, “in point of population, it is not only the grand total, but the number following the sea, or at least readily available for employment on ship-board and for the creation of naval material, that must be counted.” Mahan goes on to say that this is a quality of,

“staying power… which is even greater than appears on the surface; for a great shipping afloat necessarily employs, besides the crews, a large number of people engaged in the various handicrafts which facilitate the making and repairing of naval material, or following other callings more or less closely connected with the water and with craft of all kinds.”

But even in front-facing maritime industries, America falls behind, as evidenced by the Maritime Administration (MARAD) finally sounding the alarm on mariners available for the ready reserve fleet in a war against a thoroughly maritime nation with a maritime militia and weaponized commercial fleet.

These maritime qualities expand beyond mariners and their supporting maritime industry. From commercial electronics to drone manufacturing, China fields vast and ever-improving professional communities in pursuits related to the development, sustainment, and operation of a modern Navy. Mahan recognized that “such kindred callings give an undoubted aptitude for the sea from the outset.”

Even industries unassociated with naval warfare provide those with the character and skill needed to support the fleet. Mahan notes a particularly canny English mariner, Sir Edward Pellew, who, “when the war broke out in 1793… Eager to get to sea and unable to fill his complement otherwise than with landsmen, he instructed his officers to seek for Cornish miners; reasoning from the conditions and dangers of their calling… would quickly fit into the demands of sea life. The result showed his sagacity… he was fortunate enough to capture the first frigate taken in the war in single combat.” China’s multitude of industries provides such individuals experienced in the conditions and wielding the skills sufficient to make useful mariners.

The U.S. Navy highlighting contemporary quality recalls Mahan’s unnamed French officer, who after “extolling the high state of efficiency of the French fleet… goes on to say: ‘Behind the squadron of 21 ships-of-the-line which we could then assemble, there was no reserve.’”

China certainly displays Mahan’s qualities for a maritime nation’s industrial character and its relation to the sea. The CCP’s groundwork of capacity is now well laid to improve the qualitative muscles at sea, opportunities well in excess of the U.S. Navy’s.

Practice Makes Perfect – But How, When, and With What?

When faced with the ever-growing size of the PLAN, a common U.S. Navy response is that, “they script their people to fight, we actually train our people to think.” While valid, the United States Navy has had its own past struggles with training quality and scripting. Meanwhile, the PLAN pursues improvements in the quality and accurate assessment of its combat exercises.

Only nine years ago the surface fleet founded the Surface and Mine Warfare Development Center (SMWDC) to repair decades of atrophy in tactical and operational training and expertise. Still, scripts and constraints continued to erode junior officers’ desire to command while early command opportunities decrease. From my own experience, experienced, post-command mentors wondered aloud if seeking command at sea was and is worth the ever-shrinking margin of actual command exercised against a sea of requirements.

Ship for ship, the U.S. Navy is still better than America’s PLAN adversaries. U.S. Navy waterfront leadership’s resentment of administrative leashes indicates they still strive for independence and know what right looks like. However, institutionally the U.S. Navy fails to detect the diminishing opportunities for excellence that its size and those leashes provide, and how the opposite opportunity is now offered to America’s principal adversary. The diminished size of the U.S. fleet against growing operational requirements requires leadership to impose ever greater oversight and ever smaller margins of independence, while the PLAN’s mere size allows broad new opportunities for autonomy and professional growth if they want to pursue it.

To demonstrate these narrow margins, during the roll-out of the 36-month Optimized Fleet Response Plan, my officemates and I at the Surface Forces Atlantic Commander’s Action Group did a loose internal analysis projecting the cycle over time. We determined that scenarios existed in which the margins imposed by the historically low fleet size in 2014-2015 were such that major exercises would suffer. Our limited quantity imposed clear potential limitations on our ability to generate quality – highlighting how a lack of capacity can force greater invasive or disruptive acts to ensure the fleet-level schedule meets basic requirements.

Those invasive acts further limit a commanding officer’s ability to exercise their own judgment and build trust with their crew, as exercised during “CO’s time” – the time underway free of outside direction where a ship’s captain independently sets the agenda and priorities for training or testing.

There is no data I know of tracking the availability and use of “CO’s time,” but over the past decade I have heard its absence lamented in greater volume every year. As an operations officer (OPS), my CO tasked me with clawing back what little time I could for us to set our own destiny. Even after triple-stacking requirements just to meet our timetable, I cannot recall ever having succeeded. I have yet to meet a CO or a fellow OPS with a success story on this front. The fleet’s limited numbers often force condensation and scripting of training by necessity, precluding greater independent opportunities for teams to develop and exercise their tactical creativity.

Additionally, the U.S. Navy’s often minimalist approach to procurement shows how limited quantity limits development of quality in arenas like tactical and technical development. As an example, the 10-years-behind-schedule LCS Mine Counter-Measures (MCM) Mission Package (MP) has still yet to certify Full Operating Capability. When I was OPS with LCS Crew 206 in 2020, when the package was only seven years behind schedule, we could only field a single unmanned surface vessel (USV) for limited periods to conduct basic testing – let alone tactical development. This was after the disastrous attempt to base the MCM mission package off the Remote Multi Mission Vehicle (RMMV) – a corner-cutting approach that tried to repurpose a program from 1999 for DDGs into an LCS minehunting system into the 2020’s.

Among numerous other programmatic issues, the paucity of resources always limited the speed of development. The U.S. Navy is making strides learning from that failure on the unmanned front with CTF 59 in Bahrain, USV DIV One in San Diego, and a new approach for 4th Fleet. Nonetheless, the US Navy remains well short of needed manned surface vessels. As the qualitative lag in the MCM MP caused by a paucity of USV assets demonstrates, the same applies to manned surface vessels. But unlike the U.S. Navy, the PLAN has nothing if not extra ships, ordnance, and unmanned systems to train and experiment with.

Our Advantage Is Our People – If We Can Get Them To School

Finally, the ultimate advantage of the U.S. Navy against the PLAN is that its sailors are better on their feet. But to be better improvisers, they need training they can stand by – a lesson learned during the lost decade replacing in-person schools with CD-based SWOS-in-a-box and online GMTs.

While the U.S. Navy has greatly improve the availability and quality of training today, getting to this training demands adequate capacity: enough ships to fulfill fleet requirements while giving COs and crews the space to learn and enough sailors to cover the watch while shipmates are at school. The lack of the former is discussed above, and the 22,000 gapped at-sea billets underscore the continuing lack of the latter.

With overtasked, undermanned ships – a force cut to the bone against ever-increasing global demand for conventional maritime forces – ships are caught in a Catch-22: they need to send their sailors to school, but the persistent demands of security, engineering, maintenance, administration, domestic fleet tasking, and the like means there are very few sailors to spare.

Here, LCS shows a world that could have been, had the fleet not hamstrung its future manning with the ill-conceived Perform-to-Serve cuts. For a time, the Blue-Gold model showed what a properly manned command could do - with time for sailors to attend school, watchteams available for a month to fight entire virtual wars in the simulator, opportunity to focus on personal and family health, and opportunities to assist other crews as necessary while training along the way.

In our case, LCS Crew 206 sent 12 sailors to train on and test the USV with the prime contractor and Naval Sea Systems Command’s LCS Mission Modules program office (PMS-420) in Panama City. Properly resourced, these well-trained and well-practiced sailors achieve feats like USS Charleston’s 26-month deployment.

Unfortunately, contemporary manning gaps have made proper resourcing of any manning model a challenge. Geography also exacts an asymmetric toll: While a San Diego-based warship takes a month to cross to the Western Pacific and another month to return, a PLAN vessel can steam around Taiwan to conduct a Restriction of Navigation Operation (RONOP) on a whim. Across the roughly 425 combatants of the PLAN, that home field advantage grants years of extra operating time, which then provides the PLAN greater opportunity for professional development at every level. Whether that opportunity is properly utilized is another question – but its potential must be recognized.

Quality is Molded From Quantity

Quantity may be a quality all its own but quantity is, in jargon terms, a “force multiplier.” Quantity is opportunity – exposure to new skills, repetition and practice of old skills, and chance to develop both. Quantity is bandwidth – the capacity to cover requirements while still supporting schools, training, technical and tactical development, and innovation. The U.S. Navy may field a relative advantage in quality today but the main adversary fields capacity that enables an opportunity to overtake.

The U.S. Navy’s historically diminished size combined with the constraints necessary to maximize that diminished force’s availability paves a path to relative diminished quality against a PLAN which is growing and improving every day. If the U.S. Navy is truly serious about honing a cognitive combat edge against its numerically superior opponent, then it must recognize, advocate for, and invest in the quantity necessary to cultivate quality.

There are no silver bullets for the Navy’s most likely adversary; they are communists, not werewolves. The U.S. Navy is going to need, in laymen’s terms, “more” – not merely to fight the next war, but enough to keep cultivating in ourselves the skills and mindset to win it.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Matthew Hipple is an active duty naval officer and former President of the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC). These views are presented in a personal capacity and do not necessarily reflect the views of any U.S. government department or agency.

This article appears courtesy of CIMSEC and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.