Can We Scale Up Offshore Wind? America Has Done Far More Before

From Liberty Ships to the New Deal's electrification push to offshore oil and gas development, the U.S. has tackled far bigger projects

Fifteen years ago, I founded a company that developed high-temperature superconducting generators for offshore wind. Our customers' premise was simple: Increasing turbines lengths to reach greater power meant increasing weight at the nacelle. They needed not just efficiency, but compact size and weight beyond what permanent magnet generators could deliver to be competitive. Today, that has not yet occurred. Perhaps it's not needed.

Fifteen years ago, I founded a company that developed high-temperature superconducting generators for offshore wind. Our customers' premise was simple: Increasing turbines lengths to reach greater power meant increasing weight at the nacelle. They needed not just efficiency, but compact size and weight beyond what permanent magnet generators could deliver to be competitive. Today, that has not yet occurred. Perhaps it's not needed.

This may sound odd, but offshore wind is pretty easy technically. Big and capital intensive: yes. But the technical challenges of scaling systems of this type are well known, even offshore. We built 50,000-ton ships almost 100 years ago and can build ships ten times larger today. We were drilling offshore in 1897 and now drill into two miles of water. That's technically hard. When working with a major oil and gas company in the 2000s, we developed a technology to build an all-electric refinery entirely underground. That's technically hard.

In onshore wind and photovoltaic solar, it wasn't new fundamental technology that drove costs down – it was high volume manufacturing scale. But in marine construction, we don't generally do volume manufacturing. We do big, custom-engineered projects, with one notable exception.

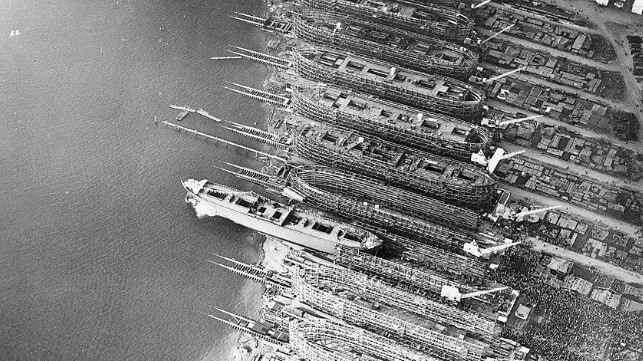

Let's take some analogies from history. More than a decade ago, I visited the fabrication yard of one of the first movers in offshore wind platform fabrication in Scotland. They had made offshore jackets for the North Sea oil industry, and the last jacket had been completed. The owners had given the company to the employees because there was no business. The company would design and assemble one massive custom-engineered jacket every 18 months for the oil industry. The nascent offshore wind business represented a vast opportunity, but it did not need custom one-offs, that big a jacket, nor could it uphold the cost to produce these jackets. For wind, the team needed to roll three identical jackets a week into the water for a year – for one small 150 MW wind farm. Nobody in the marine industry had done that since the U.S. Liberty Ships in World War II. Nobody.

Liberty Ships may be the coolest manufacturing scale-up story of all time. 2,751 Liberty Ships were built within less than four years, from 1941 to 1945. The first ones took 150 days to build, and the fastest took four days and fifteen hours to complete. By 1944, they were averaging 45 days from keel to splash. They were 441 feet long, not too dissimilar to the physical scale of an offshore wind turbine, and about the same level of engineering and manufacturing complexity, with similar supply chains. Logistics and supply chain processes had to be changed to roll Liberty Ships out at that clip, with new steel cold rolling processes to save weight, prefab component manufacturing, and even the first all-welded ships. These were rated as five-year ships but often served for two decades. Two of them are still operational today. These ships were done in 48 months at a dramatically cheaper cost than previous ships.

For perspective, if every Liberty Ship were a 7.5 MW offshore turbine, that same 48-month exercise equates to 20 GW, about four times the current annual capacity of offshore wind.

But we're not done yet. The economics and timing of renewables onshore generally depend on two site-specific variables: quality of the resource and availability of transmission capacity. Offshore has awesome wind resource quality. Transmission, not so much. And without it, offshore wind cannot be built and cannot be competitive. But we've done that at scale in short order before, too.

We run much more complicated subsea pipelines systems today all over the Gulf of Mexico in waters as deep as two miles. We've rolled out power line orders of magnitude bigger from scratch before in the Rural Electrification Act of 1936 (REA) and the Tennessee Valley Authority Act of 1933 (TVA) in the first electrification of America. Between TVA and REA, the US laid out the transmission and distribution that continue to power half of America in less than two decades. Offshore wind needs to lay a handful of transmission spines and tie-ins, by comparison, a task the offshore industry can do in its sleep. The work effort is not even in the same ballpark as we did 80 years ago.

My great-grandfather, Dean Willis Woolrich, later Dean of the University of Texas Engineering School, had started his career as an electrical and power engineer. He joined TVA as Director for Agricultural Industries in 1933. When it was formed, it was responsible for creating the demand for energy from scratch by getting electrical processes to farms and textile mills.

In his autobiography, he wrote a curious minor footnote about chairing the Grave Removal Project of TVA for Norris Dam, that first TVA hydroelectric project. Norris was built for combined flood control and power, 100 MW at the cost of $360/kW, including the dam - from scratch in 29 months. It is still operating 94 years later, with 25 percent more capacity. When the government flooded a valley for the dam and reservoir, all of the towns and their people, churches, even graveyards had to be moved within 29 months. Per his footnote, they met with committees to move 5,540 graves and 136 churches to complete this project. By comparison, offshore wind today doesn't have much to complain about regarding stakeholder management and development headaches.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

I was the Libertarian Senate Nominee for Texas in 2018, so I'm not a huge advocate of new government businesses. But rest assured, there is no question that offshore wind can scale and reduce costs if anyone cares to make it a priority. The U.S. government did not do offshore wind 100 years ago, but it showed that scaling up infrastructure of this type was doable on a fast timetable.

Neal Dikeman is a partner in Energy Transition Ventures, an early-stage venture capital firm investing in startups that drive or benefit from the energy transition, and formerly at Shell Technology Ventures. As chairman of Cleantech.org, he leads a network dedicated to bringing together scientists and entrepreneurs to commercialize cleantech and fight climate change. He was the Libertarian Party’s candidate for U.S. Senate from Texas in 2018.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.