U.S. Navy Wants Sub Suppliers to Accept 3D Printing to Speed Up Output

The U.S. Navy says that its suppliers are falling behind on parts deliveries for two critical programs, the Columbia-class nuclear ballistic missile submarine and the Virginia-class attack sub. Both newbuild programs are essential for deterrence, especially the can't-fail Columbia-class, which the Navy has pledged to deliver by 2030 despite extended delays. Because of the urgency of this multibillion-dollar problem, commercial suppliers need to let the Navy examine their production lines and insert faster methods like 3D printing, and they need to start cooperating right away, a top procurement officer said at a sub industry symposium last week.

"If you are a supplier, and your lead time is too long, and you refuse to work with us to give us your tech and help us figure out how to reverse-engineer it and how to manufacture it . . . we’re going to figure it out," said Rear Adm. Jonathan Rucker, head of the Virginia-class program office, in comments reported by Breaking Defense. "Not a threat - a fact of life."

Rucker told an industry audience at the Naval Submarine League conference that the Navy was going to find ways to get needed parts faster, and it's time to adopt nontraditional methods like 3D printing. "Time is not on our side," he said, while pledging that the Navy was not interested in taking intellectual property from suppliers who cooperate.

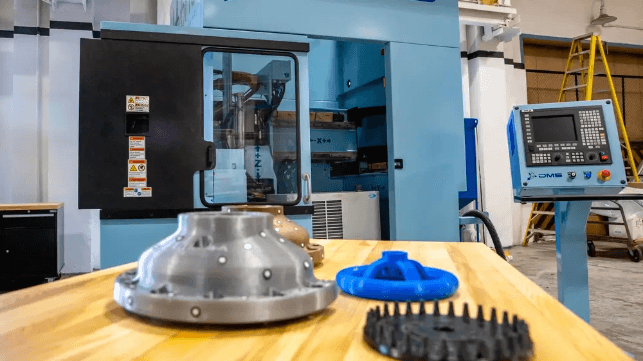

3D metal printing is a fast but expensive manufacturing method for complex parts, and in the Navy's supply base, it has historically been relegated to trial-scale projects and noncritical parts. That is beginning to change, though: Vice Adm. Robert Gaucher told the conference that the service is working on three dozen 3D-printed parts for the Virginia-class subs.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

To get to technical maturity, the Navy set up its own Additive Manufacturing Center of Excellence, which has a mission to create workable 3D printing methods and help suppliers implement them in production. Priority targets include castings, even very large parts that are usually made using sand casting. (Plastic 3D printing also helps, since printed patterns are a fast and cheap way to speed up traditional sand-cast methods.)

The need is urgent: the sub manufacturing base has shrunk by two-thirds since the end of the Cold War, and it needs to ramp up for a once-in-a-generation recapitalization program for the ballistic-missile sub fleet. Since the workforce for this massive expansion does not currently exist, the sector critically needs a robotic edge. "It's a manufacturing capacity imperative," strategic submarines program director Matt Sermon told Defense News last year.