TSB: Barge Stability Drops Off Dangerously When Overloaded

Canada's Transportation Safety Board is advising mariners to keep in mind the differences in stability between flatbottomed barges and seagoing hull shapes. A properly-loaded barge is highly stable at low angles of heel, but its righting moment tails off sooner and more abruptly than a ship's, leaving it vulnerable to capsizing once tipped - as experienced by the crew of the Arctic sealift ship Sivumut at Iqaluit, Nunavut two years ago.

The Sivumut is a geared freighter used to serve outposts in the Canadian Arctic. It carries two deck barges, Tasijuaq I and II, which are used for lightering off cargo for delivery to coastal villages. Upon deployment, the two barges are lashed together into a single unit with rods, hooks and cleats, and used as a single vessel throughout the operating season. The cargo is loaded towards the center of the barge and is not secured before making a gentle tow to shore, where the barges are beached and the cargo removed.

On October 27, Sivumut's crew were offloading cargo in Frobisher Bay, a sheltered inlet near Iqaluit. The shipowning company's CEO was on board for a visit.

At about 1430, in a routine evolution, they laid down 12 containers on the barge Tasijuaq's deck alongside the ship, then another tier of 12 on top. At this point, the barge was carrying about 340 tonnes and listing slightly to port. When the tug came alongside and took the barge on the hip for transit to shore, the tug's bow bumped into the barge's starboard side. Tasijuaq heeled to port; swayed back; then slowly heeled to port again and kept going.

As the unsecured cargo on deck slid to port, the barge began to capsize. The lines connecting it to the tug parted, and 23 out of 24 containers went into the water, along with a deckhand from the tug. As the barge's load lightened, it righted itself and returned to upright.

The tug master cast off the remains of the lines and went searching for the deckhand, who was drifting in ice-cold water along with the containers. He was found unconscious within about five minutes, floating with his PFD inflated. The tug master jumped atop a floating container to reach and retrieve him, and with the assistance of other crewmembers, he hauled the deckhand up onto the container. The victim was injured and suffering from hypothermia, and was treated by local physicians before a medevac to Ottawa for higher care.

The barge was retrieved promptly after the deckhand was recovered, and the crew immediately went after the lost cargo. Ultimately 10 boxes were recovered in a dynamic operation over several days; the remainder had to be left because the navigation season was ending and winter conditions were coming.

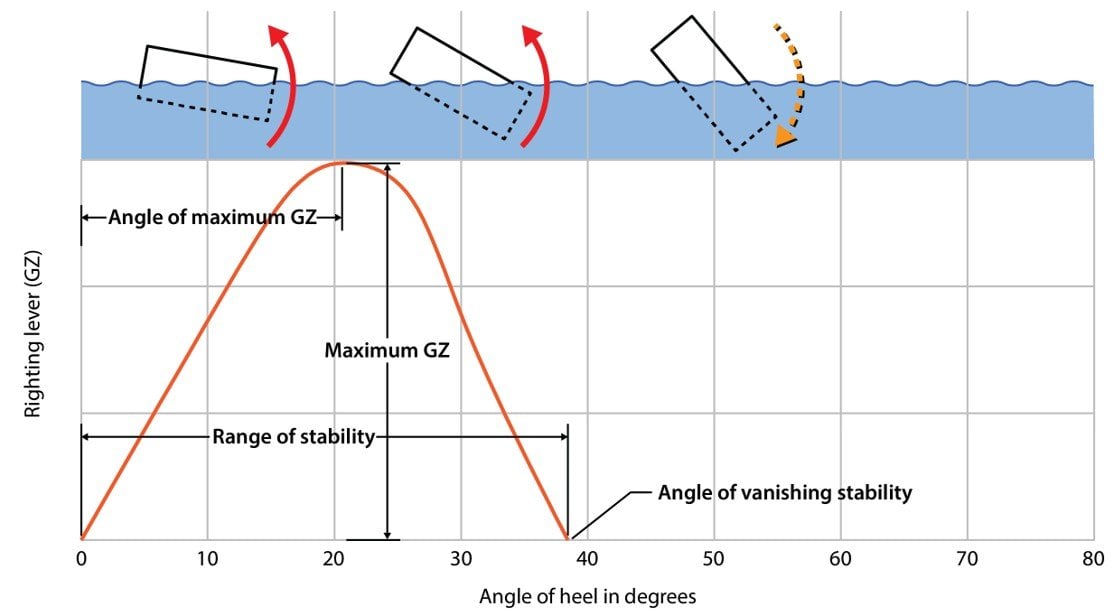

After the casualty, TSB calculated that the barge (as laden) had a positive GM of about two feet, and an angle of vanishing stability of less than three degrees of heel - after which it would likely capsize. This is a fraction of the 20-degree international code requirement for small barges, even if the barge's GM was positive.

Tasijuaq was carrying about 130 tonnes more than it was rated for in its structural arrangement plan, a copy of which was not carried aboard (carriage is not required by Canadian law). The crew and the master were not aware of the barge's limitations as described in the plan.

"Vessels with relatively wide hulls and flat bottoms, such as barges, typically have a higher initial GM and a steep righting lever (GZ) curve (peaks at smaller angles), and the range of stability is much less than a traditionally shaped vessel," TSB cautioned. "It is therefore important to ensure that the stability characteristics and loading limits are established and that the cargo crew are familiar with them."

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

GZ versus angle of heel for a typical flat-bottomed barge (TSB)