Ships' Emissions Used to Estimate Cloud Seeding Impact

A container ship leaves a trail of white cloud in its wake that can linger in the air for hours, and a new study has, for the first time, measured this phenomenon’s effect over years and at a regional scale to ultimately estimate the impact of industrialization on global warming.

Small particles in exhaust from burning fossil fuels creates “seeds” on which water vapor in the air can condense into cloud droplets. More particles of airborne sulfate or other material leads to clouds with more small droplets, compared to the same amount of water condensed into fewer, bigger droplets. This makes the clouds brighter, or more reflective.

Satellite data over a shipping lane in the south Atlantic show that the ships modify clouds to block an additional two Watts of solar energy, on average, from reaching each square meter of ocean surface near the shipping lane.

The result implies that, globally, cloud changes caused by particles from all forms of industrial pollution block one Watt of solar energy per square meter of Earth’s surface, masking almost a third of the present-day warming from greenhouse gases. Roughly three Watts per square meter trapped is today by the greenhouse gases also emitted by industrial activities.

Without the cooling effect of pollution-seeded clouds, Earth might have already warmed by 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit), a change that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projects would have significant societal impacts. For comparison, today the Earth is estimated to have warmed by approximately one degree Celsius (1.8 Fahrenheit) since the late 1800s.

“In climate models, if you simulate the world with sulfur emissions from shipping, and you simulate the world without these emissions, there is a pretty sizable cooling effect from changes in the model clouds due to shipping,” said first author Michael Diamond, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Washington. “But because there’s so much natural variability it’s been hard to see this effect in observations of the real world.”

The new study uses observations from 2003 to 2015 in spring, the cloudiest season, over the shipping route between Europe and South Africa.

Past attempts to measure the effect of ships have focused on places where the wind blows across the shipping lane in order to compare the “clean” area upwind with the “polluted” area downstream. But in this study researchers focused on a place where the wind blows along the shipping lane, keeping pollution concentrated in that small area.

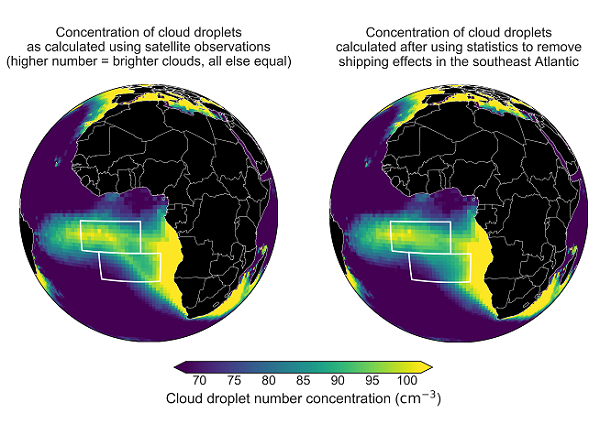

(Left) Cloud droplet concentrations from 2003 to 2015 averaged over the months of September, October and November, as observed by NASA satellites. (Right) The expected concentration of cloud droplets without emissions along the shipping route (yellow line) calculated by the new study. The difference helps explain how much industrial pollution influences clouds. Credit: Michael Diamond/University of Washington

The study analyzed cloud properties detected over 12 years by the MODIS instrument on NASA satellites and the amount of reflected sunlight at the top of the atmosphere from the CERES group of satellite instruments. The authors compared cloud properties inside the shipping route with an estimate of what those cloud properties would have been in the absence of shipping based on statistics from nearby, unpolluted areas.

“The difference inside the shipping lane is small enough that we need about six years of data to confirm that it is real,” said co-author Hannah Director, a statistician at the University of Washington. “However, if this small change occurred worldwide, it would be enough to affect global temperatures.”

The results also suggest that strategies to temporarily slow global warming by spraying salt particles to make low-level marine clouds more reflective, known as marine cloud brightening, might be effective. But they also imply these changes could take years to be easily observed.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

“What this study doesn’t tell us at all is: Is marine cloud brightening a good idea? Should we do it? There’s a lot more research that needs to go into that, including from the social sciences and humanities,” Diamond said. “It does tell us that these effects are possible — and on a more cautionary note, that these effects might be difficult to confidently detect.”

Other co-authors are Ryan Eastman, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Washington, and Anna Possner at Goethe University in Frankfurt. The research was funded by NASA and the National Science Foundation.