NTSB Reminds Mariners of Risk of Complacency

On April Fool's Day, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) issued a reminder to vessel operators of the risk of basic human error. According to NTSB, a "lack of procedural compliance and complacency" were key factors in several of the marine casualty investigations it has completed over the course of the year to date.

Manual flooding

In the sinking of the towboat Alton St. Amant in New Orleans last May, NTSB determined that a yard pipefitter sent the boat down with a water hose. After turning the hose on to fill and flush the potable water tanks, the worker left for the day, not knowing that the tank access hatches had been left open. When the tanks filled to the brim, the water flooded the engine room and the St. Amant sank to the bottom. (The bottom wasn't very far, and she was quickly refloated and returned to service.)

NTSB found that the root cause was "the absence of shipyard pre-inspection and monitoring procedures for water transfer, which resulted in potable water tanks overflowing through their open access hatches during an unmonitored transfer." NTSB investigators cautioned that crew and shipyard workers who conduct liquid transfers must check the status of a vessel’s tanks, including access hatches and piping systems, whether ashore or at sea.

Positioning error

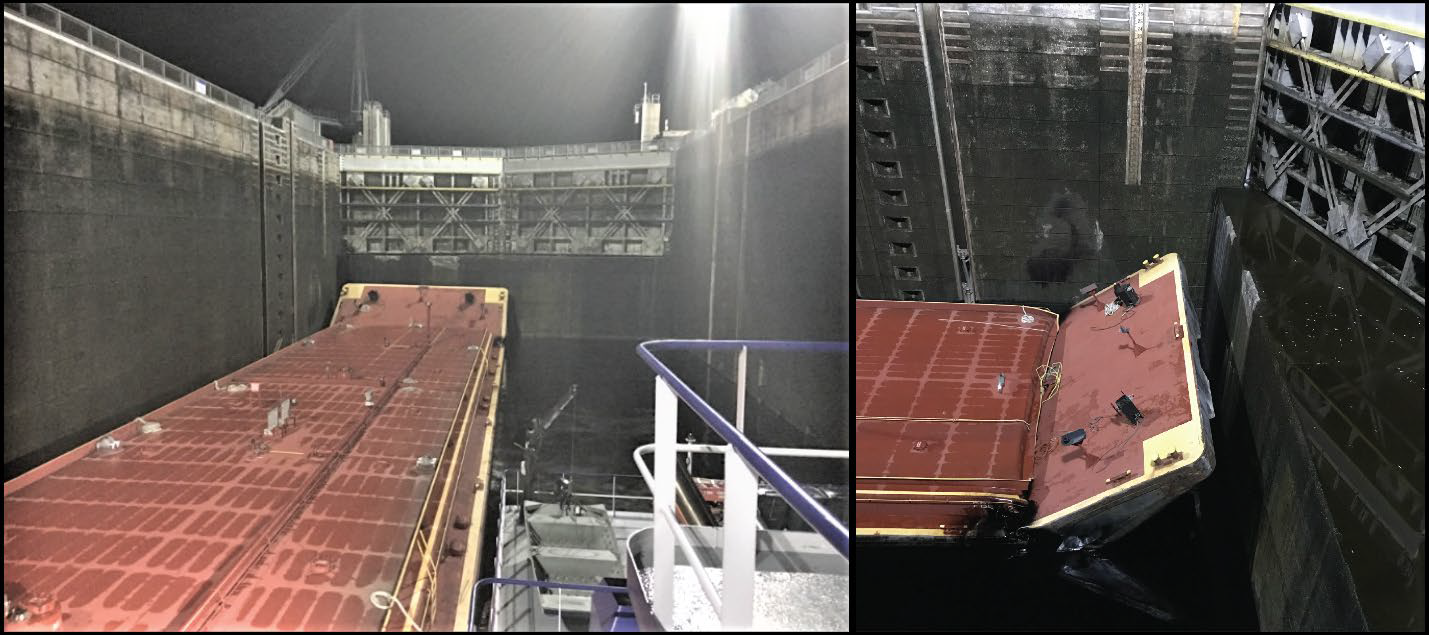

In the barge spill in the Jamie Whitten Lock & Dam complex at Dennis, Mississippi in 2019, the NTSB found that the towboat crew had not paid enough attention to the location of their tow during locking.

On the night of September 8, 2019, the crew entered the lock chamber to head downbound and made their two-barge tow fast to mooring bitts for a routine locking evolution. The 595-foot tow just barely fit inside of the 600-foot chamber.

As the process started, one of the barges drifted into a danger zone at the upper lock end of the chamber. The deckhand didn't see that the barge's rake was positioned where it would hang up on a large concrete ledge when the water level fell.

When the lock operator thought all was ready, he opened the drain valves and began the process of lowering the barges. The rake came to rest on the concrete ledge and stuck there as the rest of the barge continued down with the water.

Courtesy Savage Inland Marine (Left) and USACE (Right)

When the deckhand figured out what was happening, he called on the towboat pilot to take action, but the barge was already caught on the concrete. By the time that the lock operator learned of the situation and completed the process of shutting the valves, the water level had fallen 13 feet below the ledge.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

The barge's rake bent upwards at 45 degrees under the strain, rupturing the hull and releasing about 2,800 barrels of crude oil cargo into the lock. It took weeks to clean out the chamber, and the total cost came to about $4 million (plus another $400,000 in damage to the barge).

"Had the deck crew been vigilantly monitoring the vessel’s position, they would have noticed the barge was out of position before it became stuck on the sill and could have alerted the pilot," concluded NTSB. "Although locking operations can seem routine, the margins for safety are frequently low. Maintaining vessel position and communication with the lock operator are critical practices to ensure safe lockage. Crews should avoid complacency and vigilantly monitor lines at all times to prevent 'running' in a lock."