Hormuz and Malacca Remain Top Oil Chokepoints

The U.S. Energy Information Administration has released its 2017 World Oil Transit Chokepoints report highlighting that, by volume of oil transit, the Strait of Hormuz and the Strait of Malacca are the world's most important chokepoints.

.png)

Chokepoints are narrow channels along widely used global sea routes for oil transport, with some so narrow that restrictions are placed on the size of the vessel that can navigate through them.

The inability of oil tankers to transit a major chokepoint, even temporarily, can lead to substantial supply delays and higher shipping costs, resulting in higher world energy prices. While most chokepoints can be circumvented by using other routes that add significantly to transit time, no practical alternatives are available in some cases. Chokepoints may also expose oil tankers to theft from pirates, terrorist attacks, political unrest and shipping accidents.

.png)

Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz, between Oman and Iran, is the world's most important chokepoint, with an oil flow of 17 million b/d in 2015, about 30 percent of all seaborne-traded crude oil and other liquids during the year. In 2016, total flows through the Strait of Hormuz increased to a record high of 18.5 million b/d.

EIA estimates that about 80 percent of the crude oil that moved through this chokepoint went to Asian markets, mainly China, Japan, India, South Korea and Singapore. Qatar exported about 3.7 trillion cubic feet per year of LNG through the Strait of Hormuz in 2016, according to BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy 2017. This volume accounts for more than 30 percent of global LNG trade.

At its narrowest point, the Strait of Hormuz is 21 miles wide, but the width of the shipping lane in either direction is only two miles wide, separated by a two-mile buffer zone. It is deep enough and wide enough to handle the world's largest crude oil tankers, with about two-thirds of oil shipments carried by tankers in excess of 150,000 deadweight tons.

Strait of Malacca

The Strait of Malacca is located between Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore and links the Indian Ocean to the South China Sea and to the Pacific Ocean. It is the shortest sea route between Persian Gulf suppliers and Asian markets, notably China, Japan, South Korea and the Pacific Rim. Flows through the Strait of Malacca rose to 16 million b/d in 2016, making it the second busiest transit chokepoint.

The Strait of Malacca is also an important transit route for LNG from Persian Gulf and African suppliers, particularly Qatar, to East Asian countries with growing LNG demand. The biggest importers of LNG in the region are Japan and South Korea.

At its narrowest point in the Phillips Channel of the Singapore Strait, the Strait of Malacca is only about 1.7 miles wide, creating a natural bottleneck with the potential for piracy, collisions, grounding or oil spills. If the Strait of Malacca were blocked, nearly half of the world's fleet would be required to reroute around the Indonesian archipelago, such as through the Lombok Strait between the Indonesian islands of Bali and Lombok, or through the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra.

Several proposals have been made to build bypass options and reduce tanker traffic through the Strait of Malacca. In particular, China and Myanmar commissioned the Myanmar-China natural gas pipeline in 2013 that stretches from Myanmar's ports in the Bay of Bengal to the Yunnan province of China. The pipeline has a capacity of 424 billion cubic feet per year. The oil portion of the pipeline was completed in August 2014 and it is now operational at full capacity since the 260,000 b/d refinery in Yunnan, China, began operating in June 2017. The Myanmar-China oil line transports Middle Eastern oil.

Tanker Sizing

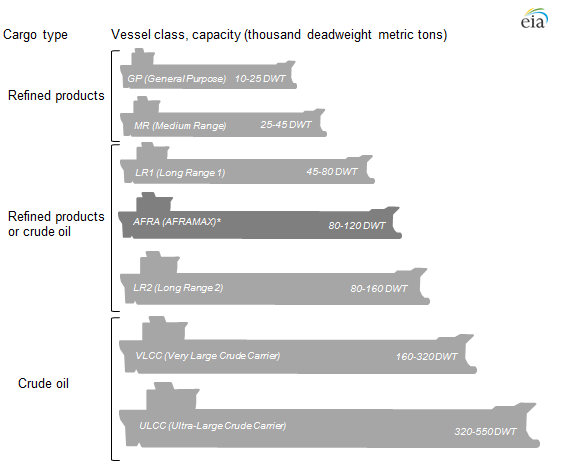

Ships carrying crude oil and petroleum products transiting certain chokepoints are in some cases limited by size restrictions. The global crude oil and refined product tanker fleet is typically classified using the Average Freight Rate Assessment (AFRA) system that was first established by Royal Dutch Shell many years ago and is now overseen by an independent group of shipping brokers.

The AFRA system classifies tanker vessels according to deadweight tons—a measure of a ship's capacity to carry cargo. The approximate capacity of a ship in barrels is determined using an estimated 90 percent of a ship's deadweight tonnage, which is multiplied by a barrel-per-metric-ton conversion factor specific to each type of petroleum product and crude oil, because liquid fuel densities vary by type and grade.

Long Range (LR) class ships are the most common ships in the global tanker fleet, as they are used to carry both refined petroleum products and crude oil. These ships can access most large ports that ship crude oil and petroleum products. An LR1 tanker can carry between 345,000 barrels and 615,000 barrels of gasoline (14.5–25.8 million gallons) or between 310,000 barrels and 550,000 barrels of light sweet crude oil. An LR2 tankers can carry 600,000 to 900,000 barrels of a petroleum product like gasoline, diesel or light sweet crude oil.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Additional ship categories, including the Very Large Crude Carrier (VLCC) and the Ultra-Large Crude Carrier (ULCC), were added to the AFRA classification system as larger vessels with better economics for crude oil shipments were deployed to serve expanded global oil trade. VLCCs are responsible for most crude oil shipments around the globe and can carry between 1.9 million and 2.2 million barrels of a West Texas Intermediate-type crude oil.

The chokepoints report is available here.