GAO: To Grow Fleet, U.S. Navy Should Reform Shipbuilding

In a new report published Wednesday, the U.S. Government Accountability Office asserts that the Navy's shipbuilding program has produced a smaller and less capable fleet than planned - and that the service needs to review lessons learned as it embarks on a historic push for a larger force structure.

Compared with a 2007 shipbuilding strategy, the Navy has spent $11 billion more and seen its fleet shrink by 50 ships more than expected over ten years, according to GAO. The office asserts that the shortfalls are due to cost growth, construction delays and quality problems post-delivery, which have all reduced the service's buying power.

Going forward, the Navy expects to spend $200 billion over ten years to sustain a 300-ship fleet. Ultimately, it seeks to build to a 355-ship force, which would require a 60 percent increase in production. To examine past challenges and inform future procurement strategy, GAO outlined twelve lessons-learned from a set of vessels built over the past decade, from merchant-classed fleet auxiliaries like the T-AKE and T-ESD to the world's most expensive vessel, the carrier USS Gerald R. Ford.

First, almost all lead ships in each class ran over budget - notably the first ships in the two LCS classes, the destroyer Zumwalt (DDG-1000), the first San Antonio-class amphib (LPD-17) and the USS Ford. Over half saw their delivery schedule slip by two years or more. In addition, the follow-on ships often cost more than expected as well, and many saw additional delays - like the two LCS classes, which are both more than a year behind schedule.

Once delivered, many of the lead vessels demonstrated extensive deficiencies - notably the LCS classes, the LPD-17 and the Ford - leading to additional cost overruns. "We have found that the Navy routinely accepts delivery of ships with large numbers of uncorrected deficiencies, including starred deficiencies, which are the most serious deficiencies for operational or safety reasons," GAO wrote. "In 2017, we found that 90 percent of acceptance trial starred deficiencies were not corrected prior to delivery for the eight ships we reviewed."

These quality and performance issues follow new vessels into the fleet. GAO highlighted in particular the well-reported issues with the two LCS variants, which have had challenges meeting survivability and warfighting requirements, and with the LPD-17 class, which have experienced multiple issues related to their main propulsion, control systems and electrical systems.

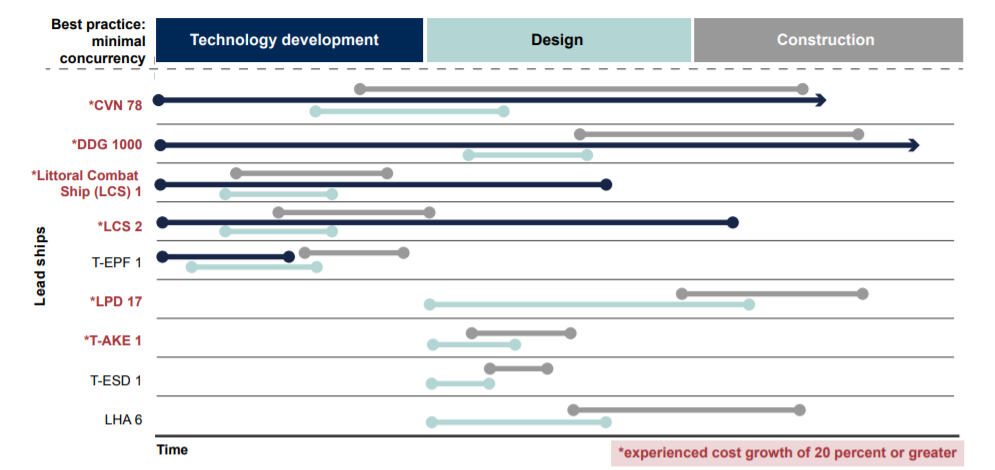

GAO claims that these patterns are the result of a procurement process that rewards overstating ship capability and understating price to win congressional funding authorization. When this results in problems in mid-construction, the service is forced to alter its plans (and its hulls) at high cost, eroding its buying power. Defeating these procurement risks requires expertise, GAO asserts. "We found that successful shipbuilding programs have sound business cases, starting with the lead ship, built on attaining critical levels of knowledge at key points in the shipbuilding process before significant investments are made," the office wrote. Knowledge includes thorough management of risk by conduction R&D and design early in the development process. Without testing and developing immature technologies and finalizing a design before construction begins, GAO said, problems may be expected.

Overlap between design, R&D and construction for recent lead vessels (GAO)

As a primary case study, the office used the example of the USS Ford, which was designed and built concurrently under the Defense Department's "transformation" policy. Construction on the Ford began well before her design and the R&D on her core systems were complete. "In August 2007, we found that, at its inception, the business case for CVN 78 [USS Ford] was predicated on unrealistic cost and schedule estimates that did not sufficiently account for risks," GAO wrote. "The Navy took delivery of CVN 78 in May 2017, but the carrier will not be ready to deploy until 2022 as significant development, construction, and testing continues."

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

At the end of construction, GAO asserts, the Navy often accepts delivery of incomplete ships in order to "alleviate some of the pressures caused by unrealistic cost and schedule estimates" and to avoid cascading delays for other hulls in the yard's orderbook. These issues persist post-delivery: the Navy structures its contracts in a manner that leaves it holding most of the risk for cost overruns, not the shipbuilder - including the risk of paying for repairs for shipbuilder-caused deficiencies. According to GAO, these contracting terms leave the government with 96 percent of the financial responsibility for fixing issues with new ships.

If the government is to move away from accepting these problems as the cost of doing business, it will have to build a sound business case for each class, not just reform specific policies, GAO asserts. "The key to overcoming the cycle of cost growth, schedule delays, and capability shortfalls in shipbuilding programs is for decision makers within the Department of Defense, the Navy, and Congress to demand that programs be supported by executable business cases. Only when decision makers embrace this more disciplined approach to buying ships will acquisition outcomes improve and the needs of the fleet be consistently met," the office concluded.