China Quietly Annexes Northeast Corner of Gulf of Tonkin

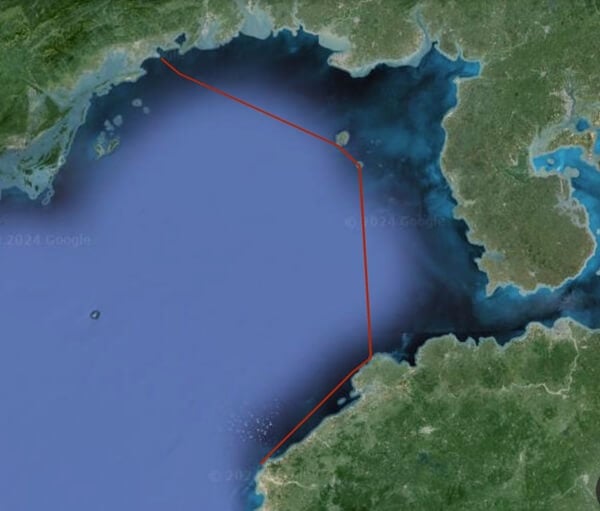

Earlier this month, China quietly turned a swathe of the Gulf of Tonkin into an extension of Chinese internal waters, simply by declaring a new baseline across the gulf's northeastern end. If Beijing's unilateral declaration stands, a crescent-shaped area extending up to 50 nautical miles from the Chinese coast will be fully subject to China's domestic laws.

Per UNCLOS, a normal baseline is the edge of the shoreline, and it is the starting point for measuring a nation's territorial sea. China has moved that starting line far offshore using UNCLOS' straight-baseline clause, which was designed to simplify maritime demarcation for complex coastlines - for example, western Norway, which is a maze of islands and fjords. Using straight baselines to "smooth" the legal shape of a rugged coastline, a nation with a fringe of islands or inlets can delineate rational maritime boundaries.

In keeping with this purpose, UNCLOS requires that straight baselines must follow the general direction of the coast, and any sea area on the landward side of the baseline must be closely linked to the nation's jurisdiction.

"It's very clear from the maps . . . that China's new baselines depart considerably from the general direction of the coast," Chatham House associate fellow Bill Hayton told Newsweek.

China's new baseline claim in the Gulf of Tonkin extends up to 50 nm from shore. The claim treats areas to the east of the line as internal waters, subject to unfettered sovereign control. (Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs / Google Earth)

The move could have the greatest effect on China's neighbor to the south, Vietnam. While the new baseline does not cross the Vietnamese-Chinese maritime demarcation line, which was negotiated and settled in 2000, some analysts warn that it could form a basis for future claims to Vietnam's waters. It would also allow China to exercise full administrative control over all navigation in the northeastern end of the gulf and the Hainan Strait, with potential effects on Vietnamese shipping interests.

"Vietnam believes that coastal countries need to abide by the UNCLOS when establishing the territorial baseline used to calculate the width of the territorial waters and to ensure that it does not affect the lawful rights and interests of other countries, including the freedom of navigation, and the freedom of passage through straits used for international maritime activities in accordance with UNCLOS," said Vietnamese foreign ministry spokesperson Pham Thu Hang last week.

China's foreign ministry has been unapologetic. "It's China's legitimate and lawful right to determine the territorial sea baseline in [the Gulf of Tonkin]," foreign ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin said last week.

Vietnam and China have a long history of confrontation in the South China Sea, but relations have recently been warming. Vietnam signed a joint maritime patrol agreement with Beijing last year, and the first formal arrangements for joint Vietamese and Chinese coast guard operations were discussed just last month.

Vietnam's response to the new Chinese baseline has been muted so far, but Western analysts warn that the changes to the chart could cost Hanoi down the line.

"It gives reasons for China to question the agreement that Beijing and Hanoi signed off in 2000 and push the boundary closer to the Vietnamese coast," said Alexander Vuving of the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, speaking to RFA.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

The baseline declaration could also be an early test of a much larger enclosure. In 2022, the Chinese government announced that it has the right to encircle the waters of four Chinese-occupied island groups across the South China Sea with straight baselines, thereby expanding the extent of its internal waters hundreds of nautical miles offshore. The U.S. government disputes this "Four Sha" straight-baseline claim and has conducted freedom of navigation operations to challenge it.

UNCLOS' rules for baseline demarcation allow the coastal state to draw around low-tide reefs and shoals as though they were real islands, if they have been artificially built up to support a lighthouse. China's controversial campaign of expansion in the Spratly and Paracel archipelagos has turned multiple low-tide elevations into island military bases; many of these megaprojects started with a public emphasis on lighthouse construction.