Grounding: Helmsman Confuses Port and Starboard

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) has attributed the grounding of the general cargo ship Bosphorus to team pilotage failures as a result of the helmsman confusing port and starboard.

The vessel grounded at Lytton Rocks Reach in the Brisbane River in October 2013 after the ship’s helmsman unintentionally put the helm the wrong way. By the time that the Brisbane Marine Pilot on board the ship realized that the helm had gone the wrong way, it was too late to prevent the ship from grounding in the narrow section of the river. There were no reported injuries, damage or pollution as a result of the grounding.

The ATSB’s investigation found that the application of incorrect helm was not identified by the ship’s crew and that the ship’s safety management system documentation provided no guidance in relation to the allocation of function based roles and responsibilities to members of the bridge team during pilotage.

The investigation also found that the navigational watch was handed over at a critical point of the pilotage and the risks associated with this change were not considered. Furthermore, neither the ship’s safety management system nor the Brisbane Marine Pilots’ passage plan detailed any guidance or instructions relating to handing over the watch or helmsman during high risk areas of the pilotage.

While functional roles and responsibilities should always be clearly assigned to each bridge team member, the pilot, the master and the officer of the watch should all check the rudder angle indicator before and after each helm order, reports ATSB.

The incident in detail

At the time of the accident, the bridge team consisted of the master, chief mate, as officer of the watch (OOW), and a seaman acting as the helmsman. At 1609, a Brisbane marine pilot was embarked for the inbound transit of Moreton Bay, the Brisbane River and to the berth. The master and pilot exchanged information regarding the ship, the inward passage and the berthing manoeuvre and they agreed on the passage plan.

At the time of the accident, the bridge team consisted of the master, chief mate, as officer of the watch (OOW), and a seaman acting as the helmsman. At 1609, a Brisbane marine pilot was embarked for the inbound transit of Moreton Bay, the Brisbane River and to the berth. The master and pilot exchanged information regarding the ship, the inward passage and the berthing manoeuvre and they agreed on the passage plan.

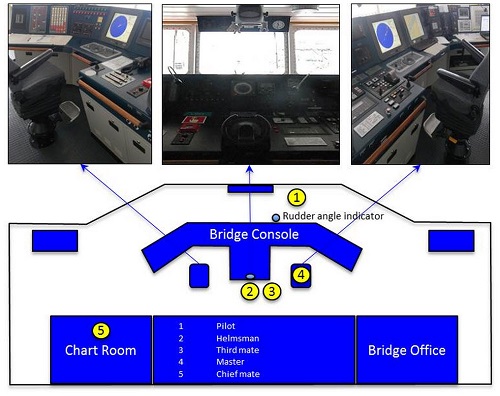

The pilot took the conduct of the ship and then completed setting up his portable pilot unit (PPU). The master moved to the bridge office on the starboard side of the bridge to undertake other administrative duties. The passage proceeded in hand steering with the chief mate monitoring the ship’s position from his seat in front of the port radar. The ship transited the bay without incident.

On approach to the Brisbane River, the master assumed his seat in the chair in front of the starboard radar. The pilot was standing to the starboard side, in between the bridge control console and the table on which his PPU was located. At 1934, as Bosphorus was transiting the entrance channel and approaching the Outer Bar Reach the helmsman was relieved by another seaman. The new helmsman confirmed the ship’s course with the pilot.

About a minute later, the ship began to veer to starboard. The pilot immediately noticed the change in heading and issued a number of helm orders to bring the ship back onto course. At about 1950, the third mate came to the bridge to familiarize himself with the situation prior to proceeding to the forward mooring station in about 30 minutes for the ship’s berthing.

Shortly after, the pilot requested a reduction of speed to 6 knots for the river transit. As the ship approached the swing basin off Fisherman Islands, the pilot gave a number of helm orders to bring the ship onto the next course of 185°T. The helmsman repeated each order and applied the helm until the ship’s heading was 185°.

At about 1958, the chief mate instructed the third mate to watch the helmsman. The chief mate then went to fill in the log book and the third mate took up a position to the right of the helmsman. The next course, through Lytton Rocks Reach, was 199°. The pilot ordered ‘starboard 5’ and then ‘starboard 10’. When the vessel was swinging to starboard, he ordered ‘midships’. He then ordered the helmsman to steady on a course of 199°. At about 1959, the helmsman informed the pilot the course was steady on 199°.

Shortly after, at about 2000, the pilot observed that the ship was not steady, but still swinging to starboard towards shallow water. He ordered ‘midships’ immediately followed by ‘port 10’. The helmsman responded verbally with ‘port 10’ but instead applied 10° of starboard helm. The pilot then ordered ‘port 20’ and then ‘hard to port’. Each time the helmsman repeated the order but applied starboard helm.

Within 9 seconds, the pilot noticed that the wheel was still to starboard and then shouted ‘you’re going to starboard’. The third mate then intervened and swung the wheel hard to port. The pilot then ordered ‘half astern’, ‘full astern’ and then for a tug to ‘come and assist’.

According to ATSB, human performance is by its nature highly variable and subject to a range of influencing factors. A person’s focus of attention on tasks can fluctuate depending on both individual and situational factors. The helmsman’s error in applying starboard helm when the pilot had requested port can be explained by examination of attentional factors.

People can become unintentionally inattentive to their primary tasks without necessarily being distracted by another external event or object. This can be seen when the helmsman initially took over the helm and the ship veered to starboard. The chief mate stated he thought the helmsman was distracted during this period.

Attentional disengagement, or mind wandering, occurs when attention which is normally directed toward the primary task momentarily shifts away from the external environment, even though the individual continues to show well practiced automatic responding. A person’s attention is unconsciously divided between internal thoughts and the task at hand, meaning the performance on the primary task may well continue at a skill based level, but without focused, conscious attention. Mind wandering or ‘zoning out’ can occur in situations where tasks are protracted, unvarying, familiar, repetitive or undemanding.

It is likely that, in the absence of any distracting or competing tasks, the helmsman’s focus of attention briefly shifted to internal thoughts. He continued to respond to the pilot’s orders, even correctly confirming the orders verbally, but without focused conscious attention. Despite there being a pilot and three deck officers on the bridge at the time, a normal variation in attentional focus on the part of a single crew member, the helmsman, over a period lasting just 35 seconds led to the grounding of the ship.

Helm orders and monitoring

Shortly after the new helmsman took helm, Bosphorus veered to starboard and the pilot had to issue a number of helm orders to bring the ship back onto course. The master and chief mate assessed the situation and, while they considered the helmsman may not have had his mind on the job, decided that he could remain on the helm if they closely monitored his actions.

On each occasion that the pilot issued an order to the helmsman, he used closed loop communication techniques to avoid misunderstandings. This was a requirement of the BMP pilotage risk management guidelines which also stated that before giving a helm order; … the pilot needs to check the rudder angle for any permanent helm that is being used to maintain course. They are to use a hand signal to indicate the direction of helm to be used not only to give a visual confirmation to the helmsman but as a cross check between the verbal order and the actual direction you wish to alter to. It is therefore appropriate to use hand signals even at night.

On 29 October, the pilot did not use hand signals during this stage of the pilotage. In addition, the rudder angle indicator could not be easily referenced from the conning position he had assumed. While the pilot could have selected a different conning position, he felt that the position he chose was dictated by the bridge design, layout and position of the available power point for his PPU.

The BMP ‘Port of Brisbane Passage Plan’, as agreed between the pilot and the master, required the OOW to monitor the helm orders and rudder angle indicator during course alterations. In addition, the other members of the bridge team had other visual indicators to monitor the situation such a chart pilot and an Electronic Charting Display and Information System (ECDIS).

In the critical phase of the pilotage, effective monitoring of the application of the helm orders by the bridge team may have enabled an early intervention to prevent the ship from grounding. However, the helm orders and their application by the helmsman was not being effectively monitored by the bridge team. Had the pilot used the phrase ‘midships’ to return the helm to a neutral position as soon as he identified it had been put the wrong way, this may have drawn the helmsman’s attention back to his primary task. However, by the time the helm was at hard to starboard and the pilot called out ‘you are going the wrong way’, it was too late to prevent the ship from grounding.