First Modern Ship Was Considered Dangerous Fad

Launched 170 years ago, the SS Great Britain was an innovation showcase that introduced a number of operational and technical innovations that became building blocks of the modern maritime world.

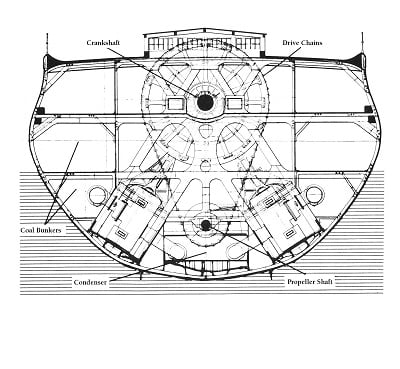

Brainchild of one of the 19th century’s greatest engineers, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Great Britain was a ship unlike any other. The first large ship with an all-iron hull, it introduced the world to such futuristic design elements as: a flat double-bottom without a standard center keel and built of cellular construction; five watertight bulkheads; a balanced rudder; a clipper bow; a hydrodynamically designed hullform; and, as its principal form of power, a large, six-bladed propeller. In 1845, Great Britain became the first ship to cross an ocean driven by propeller.

A sail-assisted steamship, the vessel was also a pioneer in the use of wire rope rigging, and the first vessel ever built with six masts (although one was removed early on). Nautical terminology having no established nomenclature for them, the masts were named for the days of the week. With an overall length of 322 feet and a breadth of 51 feet, Great Britain was the largest ship in the world and part of a radical new vision for international commerce: an intermodal transportation network.

In 1835, Brunel proposed to the UK’s Great Western Railway Company (for which he was a consulting engineer) the novel idea that the railroad line could be ‘extended’ across the Atlantic by means of a regularly scheduled steamship service. Passengers could buy a ticket at London’s Paddington Station (also a Brunel design) straight through to New York City. He insisted the ship for this service be large, putting forth the then-controversial concept of economies of scale: that a large steamship could carry its own fuel and still haul a sufficient amount of cargo and passengers to operate economically.

He supported his case by drawing on an even more controversial technology, the barely accepted science of hydrodynamics. “The resistance of vessels on the water does not increase in direct proportion to the tonnage,” Brunel argued. “The tonnage increases with the cubes of their dimensions while the resistance increases at about their squares, so that a vessel of double the tonnage of another capable of containing an engine of twice the power does not really meet with twice the resistance. Speed, therefore, would be greater with the larger vessel, or the proportion of power in the engine and the consumption of fuel may be reduced.”

%20at%20a%20launching%20%20by%20Robert%20Howlett_crop.jpg) He eventually made his case and built the paddlewheeler Great Western, an oak-hulled vessel strengthened by iron bands. Operated by the Great Western Steamship Company, the ship was 236 feet long – the biggest of the day – and its eight years of successful sailing made it the conceptual cornerstone of all oceangoing steamship service that followed. The vessel proved so profitable that the company’s board quickly authorized construction of a second ship for the service. Advancing the same concerns, Brunel succeeded in building Great Britain, which at 2,936 gross tons was more than twice the capacity of its companion. Breaking completely with tradition, the ship abandoned wood and paddlewheel for the two hotly debated new technologies of iron hull plate and screw propulsion.

He eventually made his case and built the paddlewheeler Great Western, an oak-hulled vessel strengthened by iron bands. Operated by the Great Western Steamship Company, the ship was 236 feet long – the biggest of the day – and its eight years of successful sailing made it the conceptual cornerstone of all oceangoing steamship service that followed. The vessel proved so profitable that the company’s board quickly authorized construction of a second ship for the service. Advancing the same concerns, Brunel succeeded in building Great Britain, which at 2,936 gross tons was more than twice the capacity of its companion. Breaking completely with tradition, the ship abandoned wood and paddlewheel for the two hotly debated new technologies of iron hull plate and screw propulsion.

Although iron had been used to some extent in small vessel construction for about 20 years, its use for the entire hull was considered faddish and dangerous – in fact, it would be almost another three decades before iron achieved worldwide acceptance. Meanwhile, common wisdom about propellers was reflected in the pages of Scientific American, the first issue of which coincided with Great Britain’s maiden voyage to New York:

“The steamship Great Britain, the mammoth of the ocean, which has recently arrived from Liverpool, has created much excitement here as well as in Europe; being in fact the greatest maritime curiosity ever seen in our harbor,” the magazine’s editors wrote. “If there is anything objectionable in the construction or machinery of this noble ship, it is the mode or propelling her by the screw propeller; and we should not be surprised if it should be, ere long, superseded by paddle wheels at the sides.”

The ship’s power plant was also unusual: an inverted V4-cylinder steam engine with a chain-driven propeller shaft and pistons that were 88 inches in diameter, among the largest ever put to sea. At 18 rpm it produced 1,870 horsepower and could drive the vessel reliably at 14 knots, although average cruising speed was more like 10 knots. In 1984, this amazing engine was honored as an international historic engineering landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

The ship’s power plant was also unusual: an inverted V4-cylinder steam engine with a chain-driven propeller shaft and pistons that were 88 inches in diameter, among the largest ever put to sea. At 18 rpm it produced 1,870 horsepower and could drive the vessel reliably at 14 knots, although average cruising speed was more like 10 knots. In 1984, this amazing engine was honored as an international historic engineering landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

Unfortunately, after a spectacular start Great Britain was beset by problems, including an incompetent captain who grounded the vessel. Although the incident proved the wisdom of its double bottom, the vessel was underinsured and ultimately led to the company selling its two ships. Under new owners, the vessel spent 19 years carrying passengers and freight from England to Australia and was arguably the world’s fastest and most profitable long-haul carrier.

The beginning of the end came when new owners pulled the engines, covered the hull in pitch pine and removed the passenger cabins, using it as the kind of vessel it had been built to obviate. Finally, losing most of its masts to an 1886 hurricane, Great Britain was abandoned in the Falkland Islands, where for more than 50 years it served as a floating warehouse in Stanley Harbor. When that job ended, the former ship of the future was beached ostensibly forever, the residents being too fond of the old vessel to scrap it.

Generous ship aficionados brought Great Britain home to Bristol in 1970 and, with some heavyweight patronage, began a long restoration campaign. The ship now rests in its original graving dock, which has been modified with an innovative moisture-controlling glass enclosure that protects the ship’s lower hull from further corrosion – the hull is still all-original, and in a fairly delicate condition.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Great Britain gave the world a window into the future of commercial shipping by proving the superiority of steam over sail, screw over paddlewheel and metal construction over wood, and by demonstrating the power of economies of scale. Its dramatic and successful break with the slow, evolutionary pace of maritime design provided an archetype in form and spirit for the generations of new and better ships that followed. Today again beautiful, restored as far as possible to its original specifications, the proud old ship welcomes about 150,000 visitors each year, providing a monument both to the triumphs of the past and to the possibilities of the future.

This article first appeared in ABS Surveyor magazine Summer 2014.