Electrifying Europe’s Ports: Municipal Ownership Demands New Business Model

[by Mikael Lind, Christina Argelius, Ellinor Forsström, Sandra Haraldson, Monika Przedpelska Öström, Bart Steijaert, and Henrik Åkerström]

Ports as Public Stewards of the Green Transition

Across Europe, ports are being recast not only as gateways of trade but as critical enablers of the continent’s decarbonization agenda. The EU’s Fit for 55 package mandates a 55% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. Globally, shipping accounts for around 3% of CO2 emissions, while within the EU maritime transport contributes a similar share — about 3–4% of total EU emissions.

Yet shipping’s climate impact is not limited to the high seas. Port operations and port stays themselves account for a significant share of emissions. An OECD/ITF study estimated about 18 million tonnes of CO? globally in 2011 came from shipping emissions in ports, roughly 2% of total shipping emissions. More recent analyses suggest that in certain corridors, port-related activities — from maneuvering and berthing to waiting and cargo handling — can contribute 12–20% of total transport emissions. Some studies even estimate that 10–25% of a ship’s emissions may occur during port-related phases, depending on vessel type and congestion.

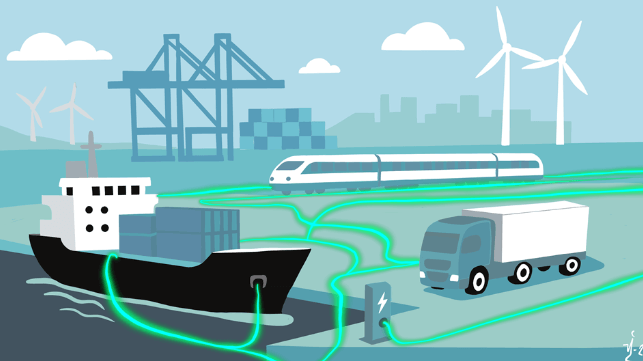

These figures underscore why electrification of port operations and provision of shore power are vital components of maritime decarbonization. Ports also sit at the interface of maritime, road, and rail transport, making them indispensable to the wider transition of Europe’s logistics system. This also connects to the emerging concept of the sustainable port, which highlights the port’s role not just as a transport node but also as an energy node — integrating renewable energy, charging solutions, and grid interaction into daily operations.

Helsingborg, Sweden’s second-largest container hub, is already home to battery-powered ferries and an all-electric tug. The port has also simulated smart charging and battery storage to investigate how to manage peak loads. Helsingborg illustrates both the potential and the strain of port electrification: while innovation is advancing, financing models and governance structures remain misaligned with the scale of the challenge.

Sweden as a Case Study: Many Ports, Many Responsibilities

Sweden’s geography makes maritime infrastructure essential. With its long coastline and dispersed population, the country relies on a large number of mid-sized ports — many governed by municipalities. These ports are central to the national strategy of shifting cargo from road to rail and sea, a move critical for both emissions reduction and infrastructure efficiency.

But ports are also facing new regulatory obligations. The EU’s Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation (AFIR) and FuelEU Maritime Regulation require widespread Onshore Power Supply (OPS) availability for container, cruise, and RoPax vessels. According to the Swedish Ports Association, meeting the electrification requirements in Swedish ports will demand an estimated capital investment of SEK 1.4–1.9 billion (€120–165 million), plus ongoing annual operating costs of SEK 150–250 million (€13–22 million). For municipally governed ports, these figures represent not only a daunting upfront challenge but also a long-term financial burden. Private ports face the same electrification challenges — and in some cases even greater ones — since they operate as stand-alone entities without the possibility to rely on capital or cross-subsidies from other parts of the municipality where they are located.

The implication is clear: no single municipality can absorb this burden alone. The only realistic path forward is to pool efforts so that funding criteria can be shaped, and project pipelines built, in ways that unlock national and EU support. But above all, what is needed is not more planning, but money for execution.

The Financing Dilemma

Electrification is not optional but a regulatory requirement—though its scope varies with vessel size and port call frequency. But the question of how it should be financed remains unresolved.

Ports operate under thin margins, and the prevailing model for OPS is to charge vessels a basic connection fee and pass through the cost of electricity. While this ensures cost recovery on a per-call basis, it rarely generates sufficient revenue to justify the multimillion-euro investments required. In practice, OPS is often treated as an environmental or reputational commitment rather than a profitable business line.

Swedish law compounds the challenge: ports are not permitted to profit from electricity sales, since only licensed energy companies may sell electricity with a margin. Even if OPS demand were to increase sharply, ports cannot develop a business case around energy provision.

Public subsidies can provide partial relief, but these too have limitations. Sweden’s Klimatklivet program, for example, explicitly excludes funding for measures that ports are legally obliged to implement. Because OPS is now mandated under EU law and transposed into Swedish regulation, Klimatklivet cannot be used to finance these investments.

The result is a significant financing gap. National and EU mechanisms — such as Klimatklivet and the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) — exist, but they are competitive, fragmented, and insufficient to match the scale of investment required.

This makes the real task not just to design frameworks, but to channel predictable, large-scale funding into execution. Without direct investment streams — not only competitive calls — OPS deployment risks stalling before it starts.

Risks of an Uneven Playing Field

If each municipality is left to finance electrification alone, competitive imbalances will emerge. Wealthier municipalities may be able to fund their ports’ transition; smaller or poorer ones may fall behind.

This not only undermines the fairness of the market but also risks fragmenting Europe’s decarbonization strategy. Vessels will naturally gravitate to ports with better infrastructure and lower fees, distorting cargo flows and slowing the modal shift.

Collective action is therefore not about abstract cooperation — it is about ensuring that ports of different sizes can access real money for projects on equal terms, and that incentives align with regulatory mandates.

Rethinking Business Models

The situation calls for new thinking about port business models for energy provision. Several avenues are emerging:

1) Network Fees for Internal Grids: Helsingborg, together with its local energy company, is exploring whether the port can charge a network usage fee for its internal electricity grid. The model would allow the port to recoup some infrastructure costs while the energy company continues to sell electricity.

2) Joint Procurement and Shared Investments: Groups of ports could pool procurement for OPS technology and even share access to funding. This would create economies of scale and reduce disparities.

3) Utility-Based Models: Ports and energy providers can work together in deeper structural ways. One path is for ports to co-own or operate public utilities directly, as seen in the Port of Oakland and Seattle, where the port authority plays a role in energy distribution. Another approach is to create joint port–utility companies that are licensed to provide electricity, enabling ports to share in revenues and ensure cost recovery while utilities remain compliant with energy regulations. In Europe, Hamburg’s municipal model shows how shared ownership between ports and energy companies can integrate port electrification into wider energy strategies.

4) Expanded Role for National Governments and the EU: Since ports are delivering on obligations arising from EU legislation, national governments and the EU should shoulder a greater share of the financial burden.

These ideas align with the broader sustainable port concept, which positions the port as an energy node at the intersection of maritime, road, and rail systems. By combining logistics with energy distribution, ports can become both decarbonization enablers and system integrators.

But business models alone are not enough. They must be backed by hard funding: direct public investment, EU co-funding, or green bonds. Industry moves when the incentives are right — and today the incentive must be money for execution.

Helsingborg as a Prime Mover in Sweden’s Port Ecosystem

Having set the stage, it is worth returning to Helsingborg — a port already charting a way forward.

- The port today: Sweden’s second-largest container port, handling over 250,000 TEUs per year, and the main entry point for fresh fruit imports.

- Electrification already underway: two battery ferries on the Helsingør route, electrified yard equipment, and an all-electric tug has arrived in September 2025.

- System challenges: simulations show peak loads of nearly 3 MW when OPS, reefer containers, cranes, and EVs demand electricity simultaneously. Without buffers, the local grid cannot cope.

- Solutions tested: battery storage (2–4 MWh) as a buffer, smart charging systems, and new charging concepts to spread loads.

Reported in a recent study financed by Vinnova, Helsingborg’s Sustainable Port initiative has concluded with valuable insights on how climate-neutral and electrified port operations can be realized in practice. Beyond Helsingborg, the study underlines how these innovations can be scaled and applied in other ports globally, making the project a reference point for the broader port ecosystem.

Most importantly, the study demonstrates what “funding readiness” looks like: technical feasibility, stakeholder alignment, and financial planning combined. These are the kinds of structured projects that should guide real funding decisions — and be backed with money for implementation, not just planning.

Grid Capacity: A Growing Bottleneck

Even if ports secure financing, another obstacle looms large: grid capacity.

In many parts of Sweden, local electricity networks already operate close to their limits. Adding megawatts of new demand for OPS, reefer blocks, and electrified handling equipment risks overwhelming the infrastructure. For grid operators, ports represent highly concentrated, time-sensitive demand peaks — a “headache” that requires expensive upgrades and careful planning.

This means that electrification is not just a port challenge. It is a regional energy challenge. Ports like Norrköping, for example, are already working with their grid provider E.ON to ensure distribution capacity can match the port’s electrification plans — proof that OPS deployment cannot succeed without regional energy coordination backed by real investments in the grid.

Toward a Collective Path

The lessons are clear:

- Technology is not the bottleneck. OPS, batteries, and smart charging systems exist.

- Financing and governance are the bottlenecks. Municipal ownership structures make it difficult to fund investments that serve national and EU mandates.

- Grid capacity is the hidden constraint. Without parallel investments in local electricity networks, even well-funded OPS systems cannot deliver.

- Collaboration is key. Ports must not compete individually on OPS models; they must coordinate to present a unified position to regulators and financiers.

That coordination should not stop at associations — it must deliver concrete, funded projects. Europe has the mandates. The technology is ready. What is missing is money for execution.

Conclusion: A Call for Action

Electrification of ports is not a voluntary green initiative — it is a legal requirement and a societal necessity. The technology is ready, but municipal ownership and thin margins mean that ports cannot finance OPS alone nor the wider electrification of port operations and the transport modes they serve — from ships to trucks and trains. Without predictable, large-scale funding, Europe risks creating a two-tier system of ports: those that comply and attract cargo, and those that fall behind.

The way forward is collaboration with purpose: align funding with legal mandates, build project portfolios that qualify for support, and synchronize grid planning with OPS deployment. Above all, Europe must back its climate ambitions with real money for execution — or risk seeing port decarbonization remain a paper exercise instead of a climate solution.

Mikael Lind is the world’s first (adjunct) Professor of Maritime Informatics engaged at Chalmers and Research Institutes of Sweden (RISE). He is a well-known expert frequently published in international trade press, is co-editor of the first two books on Maritime Informatics and is co-editor of the book Maritime Decarbonization.

Christina Argelius is the CTO at the port of Helsingborg. Before that she has been working in the car industry in various positions within technical development and facility management. Christina has a mechanical engineering degree from University of Chalmers in Gothenburg (SE).

Ellinor Forsström is an engineer and project manager at RISE specialized in the subject of maritime energy systems. She has led the work in several research projects/initiatives concerning alternative fuels in shipping and increased energy efficiency onboards ships as well as similar projects in port areas.

Sandra Haraldson is Senior Researcher at Research Institutes of Sweden (RISE) and has driven several initiatives on digital collaboration, multi-business innovation, and sustainable transport hubs, such as the concept of Collaborative Decision Making (e.g. PortCDM, RailwayCDM, RRTCDM) enabling parties in transport ecosystems to become coordinated and synchronised by digital data sharing.

Monika Przedpelska Öström is the Head of the Ports of Sweden Association. Ports of Sweden is one of seven associations within Transportföretagen, the trade and employers’ organization for the transport industry. Today, Ports of Sweden has 60 member companies and approximately 4,000 employees in the port sector. Among its members are both port owners and port operators, as well as other companies that provide services in and around the ports.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Bart Steijaert is CEO at the port of Helsingborg and has been working internationally in the port and logistics business since 1996. Bart has logistics engineering degree from Universities in Vlissingen (NL) and Ghent (B).

Henrik Åkerström is the CEO of Port of Norrköping and has extensive experience in the transport and logistics industry across land, sea and rail.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.