The Rise and Rise and Rise of Polar Cruising

Polar cruising commenced in the late 19th century when a German industrialist chartered ships that accompanied whale catchers to Spitsbergen in the Svalbard Archipelago. There they could join the whaler to watch the action. This tourism activity was part of a multifaceted enterprise encompassing coal mining and fishing. It wasn’t financially successful, but no doubt adventurous travelers took advantage of northern Norwegian marine activity out of Tromso, as cruises to the Svalbard Islands continued into the early 20th Century.

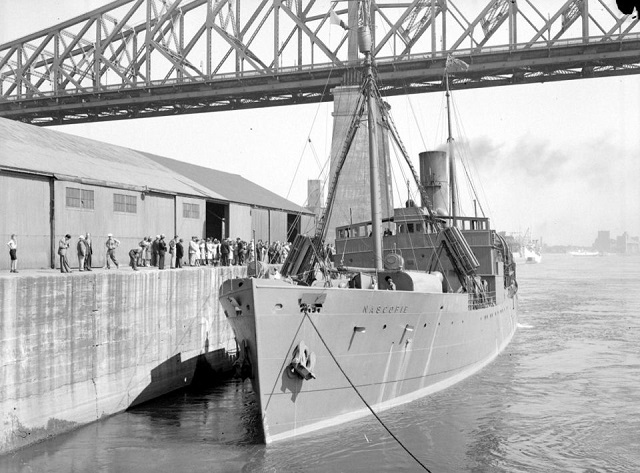

The Hudson’s Bay Company tried, unsuccessfully, to mount a cruise to Hudson Bay in 1923, using the Canadian Pacific Liner Montreal. Regrettably, insufficient tourists signed up, and deposits had to be returned. In 1933, the company started offering limited cruise passenger accommodation on their re-supply vessel ss Nascopie, and cruises were offered from Montreal to Churchill, or vice versa or round trip until 1941.

Modern day Polar cruising is generally considered to have commenced in 1969 when Lars Erik Lindblad built the 2,398-grt 104-passenger Lindblad Explorer, and began offering specialist expedition cruises. The ship visited the Canadian Arctic in 1974 when it called at Cape Sherard in late July, probably as part of a Greenland cruise as she then came back to Canada with calls at Clyde River and Pond Inlet in early August. The ship returned to the Canadian Arctic in 1982 and 1983. Then on August 20, 1984, the ship left St John’s, Newfoundland, bound for a 43-day voyage through the Northwest Passage that would take her to Yokohama on September 29, thus becoming the first passenger ship to transit the Northwest Passage.

Marine tourism to polar regions is expanding rapidly, although Canada has perhaps the smallest number at about 3,000 marine visitors per year. By comparison, the Antarctic had some 45,000 marine visitors in 34 cruise ships over the 2016 - 2017 season, while there were 41,000 marine cruise visitors to the Svalbard Islands in 2016. Many of the air arrival passengers to Longyearben then took four-five day local cruises around the archipelago.

In Greenland, 26,000 cruise tourists visited on 41 cruises by 31 cruise ships. As with Svalbard many air visitors were going elsewhere, embarking on cruises to the Canadian Arctic. Greenland has excellent air uplift capabilities compared with Canadian Arctic communities, added to which cruising in Canadian waters requires a reported 35 permits of one sort or another, while Greenland only requires five.

In 2016, the cruising event that captured considerable attention was the Northwest passage by the non ice classed Crystal Serenity. Their planning was impeccable, but the use of the British Antarctic re-supply vessel Ernest Shackleton as an escort, coupled with generous community donations, has set a very high bar for other operators of large cruise ships seeking to emulate their success. Even Crystal has decided not to offer another Northwest Passage until their first expedition ship – Crystal Endeavour - is available. Originally scheduled for 2019, delivery has slipped to 2020; it is not known whether the three ship program has slipped by a year.

The switch to a smaller ice classed, but just as luxurious ship, was perhaps encouraged by the fact that the 2017 cruise did not sell out. With about 740 guest in 2017 compared with around 969 in 2016, margins would have been much reduced and the Shackleton charter must be quite costly. Thus future polar cruises with a ship that does not require an escort would be more attractive. However, it should be noted that the Crystal Serenity also undertook an Antarctic cruise in 2016/17 without an escort, although with only 734 passengers.

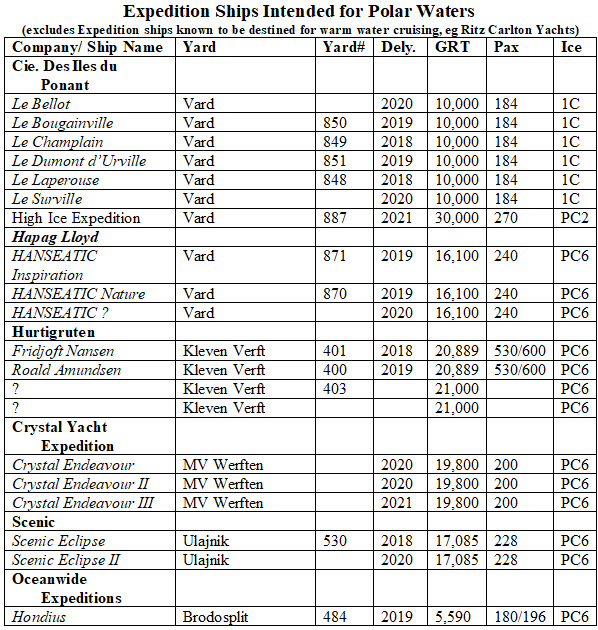

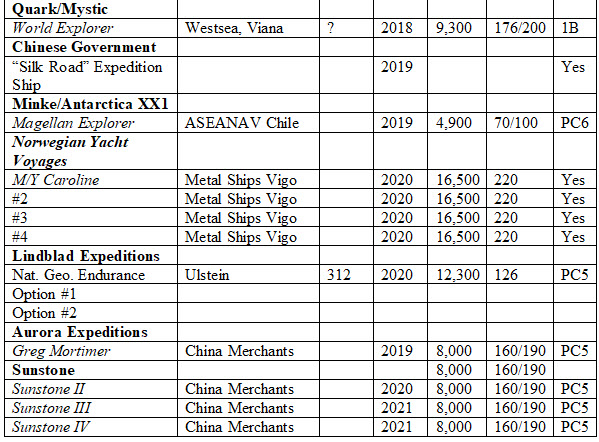

Polar expedition vessels seem to be the current fad for the cruise industry with established operators, like Crystal, seeking multiple vessels. There are also many new operators seeking to get into the business, as the following table shows.

As will be seen, there are a remarkable 32 polar expedition style cruise ships on order, most are targeted at an ultra luxury experience, and it is interesting to use the Hapag-Lloyd ships as an example of how the market is changing; with 67grt/passenger for the HANSEATIC Inspiration compared with their earlier flagship expedition vessel Hanseatic at 46grt per passenger; Hanseatic moves to the OneOcean fleet as RCGS Resolute.

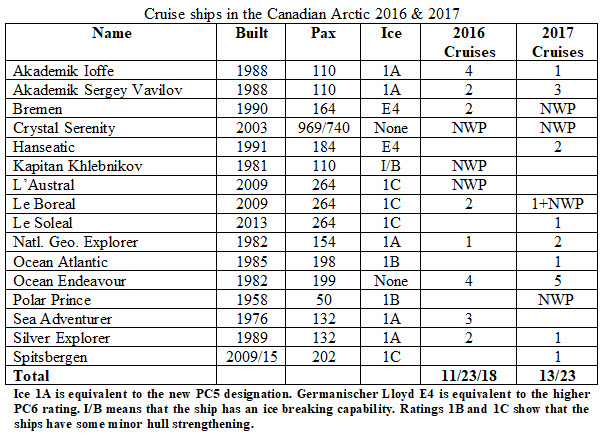

While there are a ton of new ships coming into the expedition fleet, the old ones aren’t going away any time soon. The list of ships in the Canadian Arctic for 2016 and 2017 gives a good idea as to how many old stalwarts there are. As long as the owners can justify the upgrades to keep the ships current, they will continue to be available for cruises.

While the focus is on cruise ships, there are many others who cruise in polar waters, adventurers, mainly small sailing or motor assisted vessels under 30 meters in length and also mega yachts which are sometimes the size of small cruise ships. For example Paul Allen’s Octopus, which has a PC 6 ice rating has been a frequent user of the Northwest Passage.

In Canada, a remarkable 23 adventurers, mainly in craft under 15 meters in length made a Northwest Passage in 2017. Also not counted in the numerous ships are very small expedition vessels with up to 12 passenger accommodation. There were 15 such vessels in Antarctica in 2016-2017.

About the Author

Christopher Wright is the retired principal of The Mariport Group Ltd., and has been involved in Arctic studies since 1973. In the late 1990’s he successfully worked to bring luxury overnight cruising back to the Great Lakes of North America. He currently works with the consulting group Advisian as a Marine Logistics Specialist. He is also the author of Arctic Cargo: A History of Marine Transportation in Canada’s North. He maintains a web site concerned with Canadian Arctic History and recently posted a paper on the History of Cruising in Canada’s Arctic at www.arcticcargo.ca.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.