South Africa Trade Returns to Growth, But East Africa Rising

Industry analyst Dynamar has released its East and Southern Africa (worldwide) Container Trades 2019 by Darron Wadey, noting South Africa struggled in 2017 but has now seen a return to growth.

The East Africa, Southern Africa and Indian Ocean Islands trade, abbreviated as ESAf, has a coastline stretching some 21,000 kilometers, with fronts on the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Only part of South Africa and all of Namibia possess South Atlantic coastlines.

In 2017, the total value of the ESAf economies reached $737 billion, less than one percent of the global economy. Southern Africa is dominant in the region regularly accounting for around 60 percent of the total. East Africa is however growing quickly and has seen its share rise from 34 percent in 2013 to 40 percent in 2017.

South Africa experienced a five percent drop in GDP from $367 billion in 2013 to $349 billion in 2017. This is as much an issue of a weak South African currency against the U.S. Dollar than anything else, says Wadey. However, in the five-year period to 2022, Dynamar expects the ESAf region’s economy to grow by $268 billion to $1,006 billion, with South Africa set to return to sustained growth but at a lower rate.

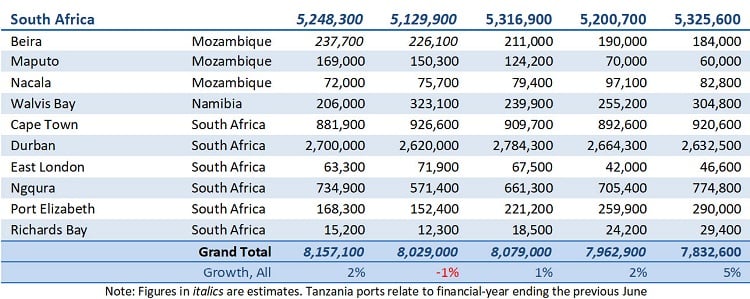

22 ports are called at by intercontinental liner services. Five are located along the East African coast, 10 in Southern Africa, with the rest being located on Indian Ocean Islands. The two largest ports continue to be Durban (2,700,000 TEU) in South Africa and Mombasa (1,190,000 TEU) in Kenya. This latter port took second spot from Cape Town in 2011 and broke the million TEU mark in 2014. Combined, Durban and Mombasa handled 48 percent of total throughput in 2017.

There are few private terminal operators in the region, but the construction of the multipurpose facility DP World Berbera is underway. DP World (51 percent), Somaliland (30 percent) and Ethiopia (19 percent) own what could be a new gateway to landlocked Ethiopia.

At the start of 2019, there were 18 different carriers offering container shipping services to and from the ESAf region. This is two fewer than in 2017 and is the lowest number noted by Dynamar in over a decade of review.

Singapore headquartered ONE encompasses former participants “K” Line and MOL, Hamburg Süd and Simatech have exited altogether. ZIM via Gold Star Line has made a return to the trade.

The Far East, Middle East/Indian Subcontinent and Europe/Mediterranean are the main trade areas connecting with ESAf. Over the five-year period to 2017, carryiers have struggled, experiencing declines between 2014 and 2016. Dynamar estimates carryings for the whole of ESAf to have reached over five million TEU in 2017 compared to 4.7 million TEU in 2016. The containerized trade is forecast to reach seven million TEU in 2022 as South Africa recovers from a difficult period.

Figures from 20 ports in the region show that combined port throughput totalled 8.2 million TEU, representing four percent growth since 2013. The shares of containers handled reflect a slow drift away from Southern Africa towards East Africa and the Indian Ocean Islands.

East Africa is growing and expanding its influence. In the period from 2013 to 2017, GDP rose by 25 percent at the expense of Southern Africa. It is the landlocked countries pushing GDP growth and not so much their coastal neighbors, says Wadey. “Indeed, Mombasa and Dar es Salaam compete for hinterland cargoes to Burundi, Rwanda, Democratic Republic of Congo and Uganda in particular. State-controlled ports are under increasing pressure to improve and develop their strained infrastructure.

“Further north on the Kenyan coast stands Lamu port and associated corridor named the Lamu Port-Southern Sudan-Ethiopia Corridor (LAPSSET). In the kindest terms, this ambitious project is renowned for delays. However, the first three berths are nearing completion.

“It would seem that the race is on to capture the largest share of growing gateway throughput,” says Wadey.

The East African coastline provides a perfect example of the differences between export and import commodities. Exports are dominated by agricultural items and imports by materials used for development, equipment and machinery and vehicles. Southern Africa, especially South Africa and Mozambique, plus Zimbabwe to a degree, is known for mining including precious stones and metals, and related bulk exports.

Djibouti has strategic significance being bordered by Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia, and offering access to the state of South Sudan. Prior to 1991, the vast majority of Ethiopian trade passed through the ports of Assab and Massawa. Both are located in Eritrea, and when it gained independence in 1991, Ethiopia lost its direct access to the sea.

Next to transhipment, the vessels calling at Djibouti deliver domestic cargo for Djibouti and gateway cargoes for Ethiopia or South Sudan. Around 95 percent of Ethiopian seaborne trade is moving through Djibouti.

This leaves Ethiopia quite vulnerable to the “Djibouti Dilemma,” says Wadey. But, since taking office in April 2018, the new Prime Minister has introduced reforms at home, improved relations with neighboring countries and signed the outstanding peace agreement between Ethiopia and Eritrea. Port and infrastructure projects are also being agreed and developed, but these require time, he says.

“Djibouti has not stood idly by.” The government has invested heavily to improve the existing gateway to Ethiopia. At the start of 2017 the 750-kilometer (466-mile) long, $4 billion electric railway to Addis Ababa was opened and later this year, is due to start moving containers. Also, the Doraleh Multipurpose Port, an extension of the Port of Djibouti, hosts six berths totalling 1,200 meters (3,900 feet). It opened in mid-2017 and offers an extra 200,000 TEU in container handling capacity and other cargo throughput capability.

“However, taking the shine off these moves, the government of Djibouti and DP World have been engaged in a contractual dispute involving the Doraleh Container Terminal. European Courts have sided with DP World, but the government of Djibouti simply nationalized the port’s stake in the venture instead. Come what may, what is certain is that DP World is no longer in Djibouti,” says Wadey. “And, for the time being, Djibouti is still key to Ethiopia’s overseas trade.”