Report: Pangolin Exports from South Africa Increasing

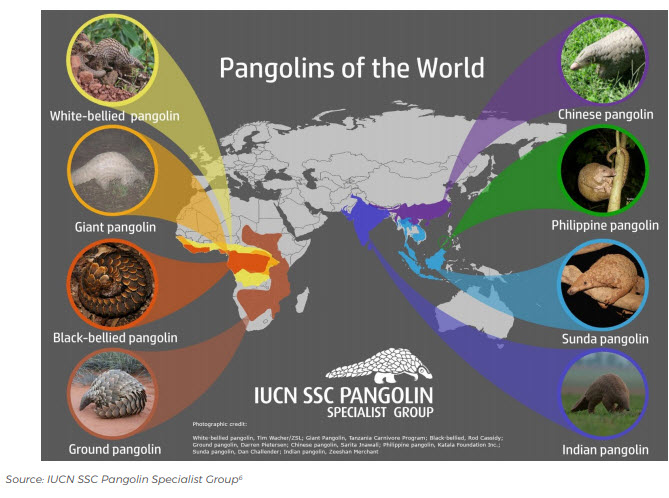

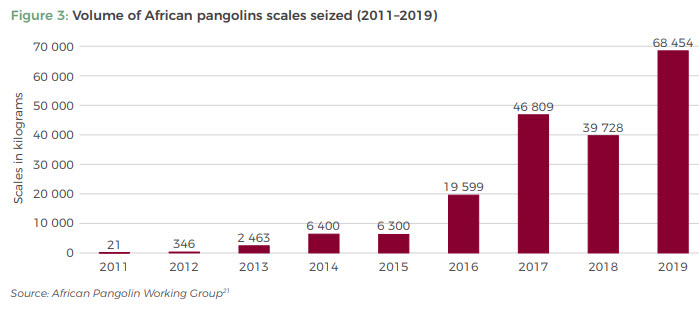

South Africa and neighboring states must act urgently to save what is already the world’s most smuggled mammal, according to a new report. The conservation NGO WildAid estimates that 100,000 pangolins are taken from the wild each year in Africa and Asia. Scales from more than a million pangolins have been traded globally in the past decade, with seizures by law enforcement surging from 21kg in 2011 to more than 68,000kg in 2019.

The decline in Asian pangolins has now seen organized criminal networks turning their attention to African species. The illegal trade has steadily moved south with gangs using South Africa to export animal products from across Africa, aided by good transport infrastructure and border controls eroded by corruption.

Profits from the illicit trade help finance terrorism, while smugglers are linked to criminal syndicates who also traffic people, guns and drugs, says Richard Chelin, author and Researcher at the ENACT organized crime program at the Institute for Security Studies (ISS). ENACT is funded by the E.U. and implemented by the ISS, INTERPOL and the Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime.

Strategies to combat illegal wildlife trafficking focus on iconic species such as rhino and elephant at the expense of lesser-known animals, Chelin said. The illicit harvest and trafficking of pangolins is not the prime focus of any specific South African government plan.

“We have to act now,” he says. “It is vital that we understand and prevent the illicit trade in pangolins before it is too late. The threat to the rhino shows that early interventions are better than reactive measures at the height of a crisis.”

In parts of Asia, pangolin meat is consumed as a symbol of wealth, and the scales and blood are used in traditional medicine.

Southern Africa is the last region with a reasonably healthy pangolin population. But the local species of Temminck’s ground pangolin is now extremely vulnerable. Failure to take decisive and coordinated action could see it become extinct in the wild in two decades.

Frontline government conservationists say bigger fines and longer sentences would help to protect endangered wildlife. Provincial legislation, such as the Gauteng Nature Conservation Ordinance of 1983, is outdated and not aligned with the National Environmental Management Biodiversity Act (NEMBA).

In the Gauteng legislation the fine for hunting a pangolin ranges from just R1 500 – R2,000, with prison sentences between 18 – 24 months. By contrast, the penalty for hunting an elephant or a rhino is a fine of R100,000, 10 years in prison or both. NEMBA allows for a maximum prison sentence of 10 years and a fine of R10 million.

“A small fine or a few days in jail is not a deterrent for organized criminals in a high-value industry,” says Fanie Masango, a specialised biodiversity officer and environmental management inspector working for Gauteng’s Green Scorpions. “The poachers are laughing at us.”

He says prosecutors, judges and magistrates need educating on the severity of wildlife crime and its impact and should be encouraged to impose hefty sentences. Masango also called for better coordination between crime intelligence, police, the Hawks and conservation officers, with standard operating procedures to ensure they share intelligence and work together.

Global agreements to combat the illegal trade in pangolins and other wildlife include the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), the UN Convention against Corruption and the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. The African Union and the Southern African Development Community have strategies to combat illegal wildlife trade, but implementation lacks funding and is not coordinated across borders.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Professor Ray Jansen, founder and chair of the African Pangolin Working Group says the pangolin is at risk of extinction in 20 years at the current rate of poaching and trade. He proposes a “chiefs and children” strategy that would see government and conservationists working with traditional leaders to protect pangolins and with schools to raise awareness of the value of wildlife to future generations.

The report is available here.