Coast Guardsmen Pioneered Flight with Wright Brothers

Story by Petty Officer 3rd Class David Weydert

U.S. Coast Guard aviators have patrolled the nation’s skies for nearly 100 years, but it wasn’t the pilots who first helped get the airplane off the ground.

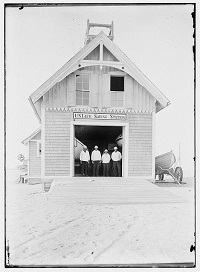

On a stretch of empty sand in the Outer Banks of North Carolina 111 years ago, a group of surfmen from Life-Saving Station Kill Devil Hills guarded the shore near the town of Kitty Hawk. The surfmen lived hidden away between the Atlantic Ocean and Albemarle Sound, within the sparsely populated lands of the Outer Banks.

Commanded by Capt. Jesse Etheridge Ward, the surfmen; Will S. Dough, Adam D. Etheridge, Bob L. Wescott, Tom Beacham, “Uncle Benny” O’Neal and John T. Daniels, patrolled the isolated stretch of sand between their own Kill Devil Hills Life-Saving Station and the four-miles north to Kitty Hawk Life-Saving Station.

Commanded by Capt. Jesse Etheridge Ward, the surfmen; Will S. Dough, Adam D. Etheridge, Bob L. Wescott, Tom Beacham, “Uncle Benny” O’Neal and John T. Daniels, patrolled the isolated stretch of sand between their own Kill Devil Hills Life-Saving Station and the four-miles north to Kitty Hawk Life-Saving Station.

Their life was that of routine, stability and endurance. The Atlantic was a treacherous neighbor, having claimed numerous wrecks along it’s shoreline throughout the years.

In 1901, two eccentric brothers from Dayton, Ohio, injected themselves into the surfmen’s quiet lives, bringing with them strange experiments and an even stranger belief.

The brothers built a small workshop just north of Big Kill Devil Hill, within a mile walking distance from the surfmen.

Surfman Adam Etheridge and his family were the first to make introductions and befriend the new arrivals, who identified themselves as Orville and Wilbur Wright and said they were there to fly.

During the next two years, the simple base-camp expanded. The original, small workshop grew in size, and a second building was built to house what would later be known as the Wright Flyer.

A casual friendship grew between the surfmen and the Wright brothers. The surfmen, fascinated with the brothers’ experiments in flight, would often volunteer by delivering the mail, assist in grocery shopping and help carry and assemble pieces of the gilders and flyers the brothers constructed and tested.

Eventually, with Capt. Ward’s permission, the brothers would fly a simple red flag from their base-camp when they needed volunteer assistance.

On Dec. 17, 1903, with wind coming from the north, the Life-Saving Station’s lookout reported to the crew the red flag was being flown.

In his diary, Orville Wright wrote:

“When we got up a wind of between 20 and 25 miles was blowing from the north. We got the machine out early and put out signal for the men at the station. Before we were quite ready John T. Daniels, W.S. Dough, A. D. Etheridge, W.C. Brinkley of Manteo and Johnny Moore of Nag's Head arrived.”

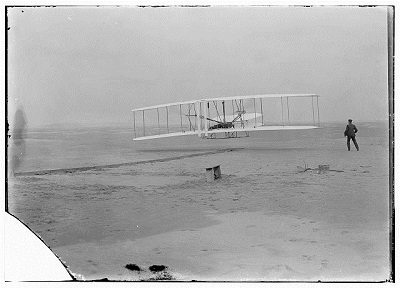

With the assistance of the surfmen and other watchers, the brothers moved the Wright Flyer to its starting position atop a simple monorail guide and trolley. Off to the side, Wilbur set up his Korona-V glass-plate box camera, focusing on a spot he believed would show the flyer’s first flight. Surfman Daniels was enlisted by Wilbur to be the camera operator and instructed in its use. It was the first time Daniels had ever operated a camera.

At 10:35, with Orville piloting, the flyer started down the monorail track and after traveling forty feet, broke free from earth’s gravity and flew.

Daniels later said that he was so excited he nearly forgot to squeeze the camera bulb, which would trigger the shutter. Fortunately, Daniels remembered to take the picture, and the photo is now known world-wide.

Daniels later said that he was so excited he nearly forgot to squeeze the camera bulb, which would trigger the shutter. Fortunately, Daniels remembered to take the picture, and the photo is now known world-wide.

The flyer’s first flight lasted 12 seconds and flew approximately 120 feet.

The men watching were ecstatic, wildly cheering and clapping, and the brothers were eager to try again. The flyer was carried by the volunteers back to the start of the rail.

The brothers took turns flying the contraption. The second and third flights were marked with small increases of time and distance, but the fourth flight, with Wilbur piloting, really took off.

As written in his diary, Orville Wright said:

“At just 12 o'clock Will started on the fourth and last trip. The machine started off with its ups and downs as it had before, but by the time he had gone over three or four hundred feet he had it under much better control, and was traveling on a fairly even course. It proceeded in this manner till it reached a small hummock out about 800 feet from the starting ways, when it began its pitching again and suddenly darted into the ground. The front rudder frame was badly broken up, but the main frame suffered none at all. The distance over the ground was 852 feet in 59 seconds.”

The jubilant group of new pilots and surfmen carried the 605-pound flyer nearly a quarter mile back to the tool shed for repairs. It was perhaps this combination of exhilaration and fatigue that led to Daniel’s own flight. While the brothers discussed their recent flights, a sudden, strong gust of wind picked the flyer up and tossed it down the sand.

While everyone released their own handholds, Daniels clung to the flyer and became entangled in the cables and chains as the flyer flew once again.

From Orville Wright’s diary:

“Mr. Daniels, having no experience in handling a machine of this kind, hung on to it from the inside, and as a result was knocked down and turned over and over with it as it went. His escape was miraculous, as he was in with the engine and chains. The engine legs were all broken off, the chain guides badly bent, a number of uprights, and nearly all the rear ends of the ribs were broken. One spar only was broken.”

Daniels fell 15 feet to the sand below and tumbled away from the flyer suffering only minor scrapes and bruises to his rib from his first flight. The force of the flyer’s errant flight and crash caused the engine block to crack in half, rendering the flyer useless.

Daniels recounted the ordeal in a 1927 interview with Collier Weekly (Smithsonian Institute)

“They were going to fix the rudder and try another flight when I got my first and, God help me, my last flight. A breeze that had been blowing about twenty-five miles an hour suddenly jumped to thirty-five miles or more, caught the wings of the plane, and swept it across the beach just like you’ve seen an umbrella turned inside out and loose in the wind. I had hold of an upright of one of the wings when the wind caught it, and I got tangled up in the wire that held the thing together.

“I can’t tell to save my life how it all happened, but I found myself caught in them wires and the machine blowing across the beach, heading for the ocean, landing first on one end and then on the other, rolling over and over, and me getting more tangled up in it all the time. I tell you, I was plumb scared. When the thing did stop for half a second I nearly broke up every wire and upright getting out of it.

“The machine was a total wreck. The Wrights took it to pieces, packed it up in boxes and shipped it back to their home in Dayton. They gave us a few pieces for souvenirs, and I have a piece of the upright that I had hold of when it caught me up and blew away with me. I wasn’t hurt much; I got a good many bruises and scratches and was so scared I couldn’t walk straight for a few minutes. But the Wright boys ran up to me, pulled my legs and arms, felt of my ribs and told me there were no bones broken. They looked scared too.”

For those few minutes, though unconventional, Daniels “flew” with the flyer, becoming the third man to fly in the Wright Flyer and the first man to be involved in an airplane accident.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

The surfmen of Life-Saving Station Kill Devil Hills witnessed the birth of aviation. Today, the U.S. Coast Guard uses its fleet of aircraft to save those at sea, keep drugs off our shores and protect our nation from foreign enemies, all thanks to the two bicycle mechanics from Ohio and the Outer Banks surfmen.

Interview with John T. Daniels, Smithsonian Institute