Understanding the Coast Guard’s Cybersecurity Rule

Applicability, Requirements, Deadlines, and Enforcement

On January 17, 2025, the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) issued its Cybersecurity in the Marine Transportation System rule, creating the first enforceable federal framework requiring U.S.-flagged vessels, Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) facilities, and waterfront facilities to implement cybersecurity measures. Some provisions are already in effect, with additional obligations phased in beginning January 2026. For owners and operators, cybersecurity is now a binding compliance requirement, on par with physical security standards.

Background and Rationale

The rule reflects the USCG’s recognition that cyber threats pose real risks to maritime operations. Past incidents have included ransomware and malware attacks, unauthorized system access, and signal interference. In 2021, for example, hackers exploited a vulnerability at the Port of Houston, stealing credentials that could have granted remote access to port systems. In 2019, the USCG reported malware disabling shipboard systems on a U.S.-bound vessel, and a separate U.S.-flagged ship in Shanghai experienced repeated GPS jamming during docking operations. Such events show how a single cyber incident, ashore or afloat, can disrupt operations, undermine safety, and ripple through supply chains.

Until now, maritime cybersecurity oversight was fragmented. Internationally, the IMO issued voluntary guidelines that were unevenly applied. Domestically, USCG security plans focused on physical threats such as terrorism and sabotage, not cyber-attacks. And although the USCG did release guidance encouraging operators to incorporate cyber considerations into their security plans, in practice, implementation varied by Captain of the Port zone and carried no enforcement authority. The new rule closes these gaps by embedding cybersecurity into existing security frameworks under the Maritime Transportation Security Act (MTSA).

Applicability and Coverage

The rule applies to owners and operators of U.S.-flagged vessels, waterfront facilities, and OCS facilities already required to maintain security plans under 33 C.F.R. parts 104, 105, and 106. It does not expand MTSA’s reach to new categories of entities but adds cybersecurity obligations to those already covered. In short, any vessel with a Vessel Security Plan or facility with a Facility Security Plan must now integrate cybersecurity into those plans.

The USCG defines an owner or operator as any person or entity that owns or exercises operational control over a covered vessel, facility, or OCS facility. This includes towing vessels with control over attached barges and facilities that control moored barges. Covered facilities range from container terminals to oil and chemicals, LNG terminals, and barge fleeting facilities. OCS facilities include offshore production platforms and mobile offshore drilling units when they are attached to the seabed and operating as drilling or production assets. The rule applies only to U.S.-flagged vessels; foreign-flagged vessels remain subject to IMO guidelines and flag-state rules.

Applicability does not depend on the size of an operator’s IT or OT footprint. Even facilities and vessels with limited systems must assess vulnerabilities and adopt appropriate measures. During rulemaking, the USCG rejected requests to exclude inland towing vessels and barges, noting that even minimal systems can expose data such as positional information or personal identifiers. Instead, all entities must conduct a Cybersecurity Assessment to determine their footprint and scale their Cybersecurity Plan accordingly. Where compliance is impractical, operators may seek relief through the waiver and equivalency process in § 101.665.

Substantive Requirements and Timing

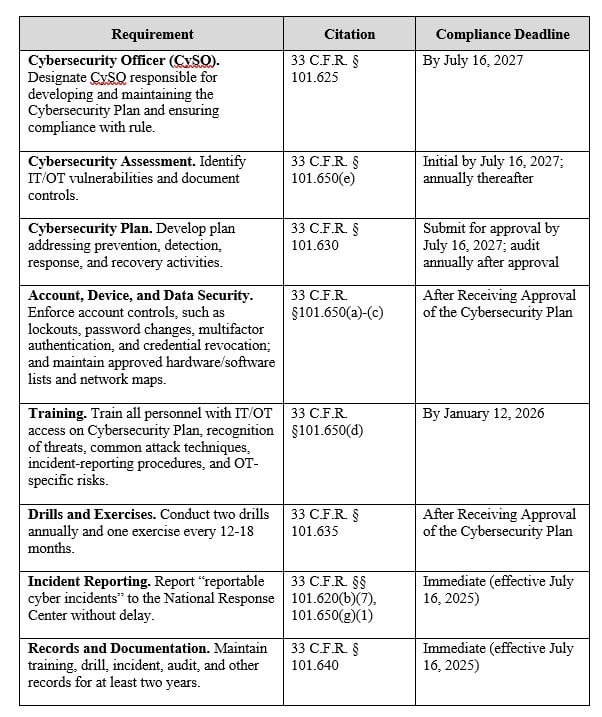

The USCG added a new subpart F to 33 C.F.R. part 101 that establishes minimum cybersecurity requirements. These requirements must be documented in a standalone Cybersecurity Plan or integrated into existing Facility or Vessel Security Plans. Some apply immediately, others on a phased schedule. Recognizing that vessels may face unique challenges, the USCG requested further comment on whether their compliance deadlines should be extended by 2–5 years. Any delay would not alter the immediate duty to report cyber incidents.

Inspections and Enforcement

The USCG will likely enforce the rule by approving Cybersecurity Plans, conducting routine inspections, and responding to cyber incidents, much as it does for physical security. While inspection schedules are set by the local Captain of the Port, the USCG is expected to coordinate with owners and operators so cyber inspections align with annual physical security inspections.

If deficiencies are identified, the USCG may start with corrective actions such as requiring fixes or issuing warnings. More serious or repeated non-compliance could lead to increased unannounced inspections, notices of violation, civil and criminal penalties, suspension or revocation of plan approvals, or in some cases stopping operations. Owners and operators should treat compliance as a serious obligation, given the USCG’s broad enforcement authority and the real risks of non-compliance. Where temporary non-compliance is unavoidable, operators must notify the Captain of the Port (for facilities and OCS facilities) or the Marine Safety Center (for U.S.-flagged vessels) and request temporary permission under 33 C.F.R. § 101.665.

About the authors:

Matthew Baker is the Practice Group Chair of Baker Botts LLP’s Privacy & Cybersecurity group. As one of the nation’s leading privacy and cybersecurity attorneys, Matthew brings his clients confidence in an increasingly complex digital landscape. With a cross-disciplinary practice spanning data privacy, cybersecurity, crisis management, and incident response, Matthew advises clients across diverse industries, helping them anticipate and mitigate emerging risks.

Austin Echols is a Senior Associate in the Houston office of Baker Botts LLP. His practice focuses on a range of environmental, health, safety, and security issues, including within the maritime industry. Prior to practicing law, Austin served in the U.S. Coast Guard as a waterfront facility inspector and pollution investigator. Austin continues to serve in the U.S. Coast Guard Reserve.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.