The Mysterious Stopover of Sparta IV Near Sardinia

For the first time since the Syrian Express started moving interesting materials for the Russian military logistics, one convoy moved in close to Italian shores, though remaining in international waters.

The sanctioned Russian-flagged freighter Sparta IV (IMO 9743033) departed Baltiysk, Russia on 31 December 2025. Sparta IV proceeded southbound from the Baltic Sea toward the Mediterranean. Sparta IV was tracked moving in parallel with another Russian cargo ship, the Mys Zhelaniya (IMO 9366110). Both ships departed from Baltiysk under the escort of a Russian Udaloy-class destroyer, the Severomorsk. Sparta IV and the other similar ships on this route have had escorts in the last two years, given the increasing risks associated to sea and aerial drone strikes and sabotage acts.

The Sparta IV's declared destination was Port Said, Egypt, but the vessel arrived in Tartus, Syria on 19 January 2026. Sparta IV then returned westward into the central Mediterranean Sea and made an abrupt change of course, shifting north into the central Tyrrhenian Sea closer to Italian shores. This is unprecedented as the ship had never transited nearby before, and this alerted the Italian authorities.

The new course put the vessel east of Sardinia on the evening of 3 February. Surface conditions in the Sardinian area were moderately rough, but well within normal limits for a vessel of Sparta IV’s size, including its related vessels. Weather data showed wave heights of about 2.5 meters at the time.

Sparta IV was escorted by the Russian Navy destroyer RFS Severomorsk and the Russian fleet tanker Kama. On 4 February, Sparta IV was in international waters off Ogliastra, east of Sardinia, alongside the other two vessels. It loitered on a north–south steady elliptic route for a few days. These maneuvers were performed at a steady speed of approximately 10-11 knots.

Italian law enforcement agency Guardia di Finanza conducted aerial surveillance with a P-72B maritime patrol aircraft. The Italian Navy dispatched the FREMM-class Frigate ITS Spartaco Schergat (F598) and monitored the Russian vessels, which shifted further north along the Sardinian coast, operating for roughly two days in the area off Capo Comino. On that side of the Sardinian coast, there are several Italian military bases and installation. Italian law enforcement and the Italian Navy maintained surveillance for the duration of this activity.

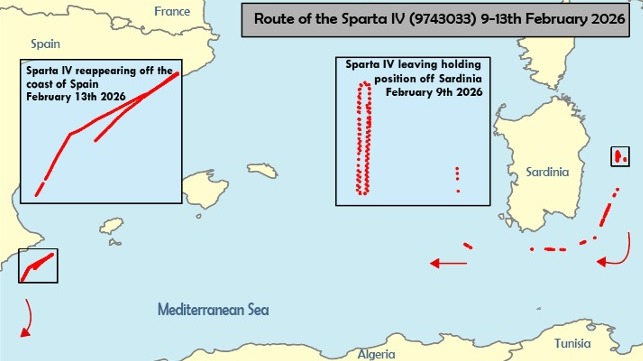

Sparta IV’s Recent Route

On 9 February, after two days, the Russian vessels sailed south down the coast towards the Gulf of Orosei. During this period, the Italian Navy added an additional FREMM-class Frigate the ITS Emilio Bianchi (F589) to assist with the monitoring of the Russian vessels‘ navigation patterns.

On Monday, 9 February 2026, at 7:22 UTC, Sparta IV possibly deactivated its AIS, triggering the Italian Air Force to launch a Beechcraft B.350ER SPYDR for surveillance. The Sparta IV possibly reactivated its AIS on Monday, 9 February 2026, at 13:55 UTC, and the Russian vessels proceeded into the Sardinia Channel on a course toward the Strait of Gibraltar. Italian Naval assets maintained surveillance of the Russian vessels as they departed the Tyrrhenian area.s

What Could have Happened

This is the first time in the history of the Sparta IV's operations that it has changed its pattern of life in this way. Since 2018, the ship has never passed so close to Sardinia on the eastern side, but only between Tunisia and Sardinia in order to reach Syria or return to Russia, often followed by NATO air patrols sent from Sigonella, Italy.

It is doubtful that the deviation is due to maritime safety reasons (waves and winds). It could have easily found less difficult anchorages or loitering areas further from a NATO’s country’s patrols. While it remained in international waters, the convoy was quite close to significant military installations, which triggered the suspicions of the Italian authorities. It remains possible that they were studying NATO’s reactions, including both aerial and naval patrols, as in previous reported cases.

This is not an impossibility considering that ships of the Russia-linked shadow fleet have previously been iplicated in intelligence operations or closely related activities, including sabotage. The Russian force involved was minimal for any kind of military escalation, so everything suggests a limited monitoring operation, given the capabilities of the vessels involved. The possibility remains that they were waiting for other ships or experiencing a malfunction.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Giangiuseppe Pili (PhD) is an Assistant Professor, James Madison University; Senior Associate Fellow, NATO Defence College; Associate Fellow, Royal United Services Institute; and Regional Director, International Association for Intelligence Education.

Peter Boerstling studies at James Madison University, Intelligence Analysis Program, School of Integrated Sciences.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.