China Has Tested Spy Balloons for Maritime Surveillance

In 2015, a Kuang-Chi ‘Cloud’ blimp acquired data from more than 2,000 ships in the South China Sea

[By Tilla Hoja, Albert Zhang and Masaaki Yatsuzuka]

China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs was quick to claim that a spy balloon breaching US territorial airspace and flying close enough to military sites to monitor them was ‘a civilian airship used for research, mainly meteorological, purposes’ that had accidentally wandered off course. Pentagon officials and the US intelligence community dismissed that claim and linked the balloon to a ‘vast surveillance program’ run by the People’s Liberation Army Air Force, partly operating out of Hainan province on China’s south coast.

Beijing’s spy balloon is a clear example of an emerging technology developed for military and intelligence operations but that crucially evolved out of civilian and scientific programs. One company that is a strong candidate for contributing to the development of the balloon—and certainly works on similar technology that it supplies to the PLA—is a Shenzhen-based metamaterials company, Kuang-Chi, which has also been sanctioned by the US government for human rights abuses in China.

Open-source documents and media reports about China’s balloon-technology programs contain sober lessons about Beijing’s incremental acquisition of foreign intellectual property and its technology partnerships with Western research institutions. This in turn highlights the difficulty in assessing dual-use technologies and serves as a reminder that Western countries need to review their scientific and commercial collaborations to ensure that those arrangements don’t allow an adversary to deploy those capabilities against their interests.

To analyse the value that China’s military leadership attaches to balloons and the near-space region (between 20 and 100 kilometres above the earth’s surface), it’s important to understand Beijing’s strategic intent and the resources it has allocated to such capabilities. Various Chinese government documents indicate that meteorological balloons, and other stratospheric airships, are important to the PLA’s aerospace strategy.

Only three major organizations in China have the capabilities to operate a balloon of the type and size spotted over North America. According to a US State Department official, one of those organizations, the PLA, likely uses balloons for military intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance. The Financial Times has suggested, based on footage of the craft, that they could potentially carry warheads.

The other two organizations are the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), which had an overall annual budget of US$24 billion in 2022—though only a few institutes within the organization work directly on balloon research programs—and the China Meteorological Administration (CMA), which had an annual budget of $5.8 billion in 2022. Both of these civilian government departments are involved in ‘military-civil fusion’ projects and collaborate with the PLA.

In October 2017, the CAS began a military–civilian project to build China’s first scientific experiment system to conduct astrobiological experiments, monitor the weather and measure electromagnetic radiation in the near-space region. According to the Project 2049 Institute, the CMA also has potential capabilities for military intelligence collection and surveillance. In 2019, the CMA implemented a 15-year plan for the development of meteorological observation technology, which states that the CMA will increase its military–civil fusion capabilities and develop systems such as a space-based global navigation satellite system reflected signal observer on long-distance, super-pressure balloons, low-orbit satellites and other airships.

The PLA, CAS and CMA have reportedly launched high-altitude balloons from at least four locations: the Da Qaidam region in Qinghai province; Urad Zhongqi Airport; a near-space aerostat experiment base in Inner Mongolia; and a base identified by The War Zone near Bosten Lake, the largest lake in China’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region, which lies next to the Malan atomic test base.

High-resolution images of the Chinese balloon crossing over the US suggest that it’s similar to balloons built by Kuang-Chi. Kuang-Chi was one of the first companies visited by Xi Jinping after he became general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party in 2012. In 2020, the company was sanctioned by the US Commerce Department for enabling ‘wide-scale human rights abuses within China through abusive genetic collection and analysis or high-technology surveillance, and/or facilitat[ing] the export of items by China that aid repressive regimes around the world’.

If and when the US publicly reveals more details about the downed balloon, one question we can hope to see answered is whether Kuang-Chi has been using new metamaterials to develop military-use balloons for the PLA. Most scientific balloons, including the type used by CAS for research, remain afloat for between a couple of hours and a few days. The flight time for a journey from China to halfway around the globe and back suggests that the balloon over the US was a ‘super-pressure balloon’ made from new metamaterials that can withstand cosmic radiation and extreme conditions while being light enough to carry a heavy payload.

Only a few civilian and military research teams have access to this technology in China. A search of patents shows that Harbin Institute of Technology, one of China’s top defence universities, has researched high-altitude balloons using new ‘aircraft skin materials’ to carry more weight and be more durable. Kuang-Chi also claims it was the first company in China to incorporate aircraft skin metamaterial (?????) as part of its balloon ‘Traveller‘ (???) program. Traveller was highlighted by China’s national broadcaster, CCTV, as a critical, innovative Chinese project that was developing super-pressure balloons.

Even if these balloons are used for meteorological research, the type of data they collect has straightforward military applications. Indeed, a PLA policy document in 2016 called for the construction of meteorological infrastructure to be integrated and standardised within the military.

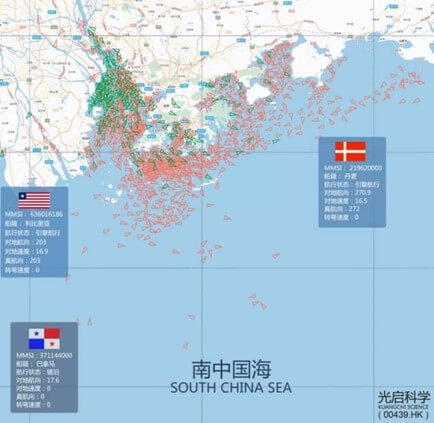

The helium blimps that Kuang-Chi builds can, it claims, capture high-definition images and navigational information such as a ship’s number, registry, latitude and longitude, course and speed. The company suggests its balloons have greater aerial surveillance capacity than traditional surveillance platforms. In 2015, the company’s ‘Cloud’ blimp acquired data from more than 2,000 ships from around 28 countries and regions in the South China Sea (see figure 1). This information would be valuable during a conflict to track an adversary’s warships and would be cheaper and quicker to deploy than satellites. On the other hand, this technology could plug the gap in many states’ maritime domain awareness.

Figure 1: Maritime surveillance data collected by Kuang-Chi ‘Cloud’ blimp in 2015 test flight. Source: Kuang-Chi, internet archive, 6 February 2015.

This evidence is consistent with documents that indicate Beijing’s aim is to militarise the use of high-altitude airships as part of a broader strategy for dominance in the near-space region. Due to the near-space region’s unique geographical advantages, the PLA perceives it as an essential part of the five-dimensional integrated battlefield of land, sea, air, space and electronic warfare. In a 2017 article, PLA researchers argued that the near-space region is becoming another geostrategic domain where other nation-states, including the US, are posturing. The science of military strategy 2020, a capstone document on the PLA’s military strategy, describes the PLA expanding the scope of aircraft to operate in near and deep space. PLA researchers have also argued that the near-space region is essential for integrated aerospace operations where long-duration balloons and uncrewed aerial vehicles play a major role in providing strategic intelligence support.

The PLA’s interest in near space was part of a transformation in its aerospace strategy. Since the 1990s, the PLA Air Force has primarily based its strategy on ‘territorial air defence’ (????), focusing on the aerial defence of mainland China. As PLA warfare doctrine shifted to incorporate more information-warfare concepts, Xu Qiliang, a former vice chairman of the Central Military Commission, proposed a doctrine of ‘integrated aerospace capabilities’ (????) emphasising reconnaissance and early warning, air defence and strategic projection capabilities. In 2014, the Xi administration formally recognised ‘integrated aerospace capabilities’ as a core PLA strategy.

Research into airships in near-space is split between high-speed and low-speed flying objects. Research on high-speed aircraft includes orbital re-entry glider aircraft and hypersonic cruise aircraft. In 2016, the PLA successfully tested its DF-ZF hypersonic glide vehicle in northwestern China, a region quickly becoming popular for military near-space tests.

Research on low-speed aircraft includes ultra-long-endurance drones, stratospheric blimps and high-altitude balloons. In 2017, Kuang-Chi tested its Traveller 3 balloon, which has potential military uses such as data collection, space–ground communication, remote sensing and telemetry. According to the CCTV report, Traveller 3 can transmit real-time information such as GPS location, balloon flying status data, surveillance video and image data to a ground station and has other avionics and flight control equipment for navigation.

In addition to data collection and communication, research is being conducted on the use of near-space airships for PLA offensive operations and support. This includes intercepting near-space hypersonic flying objects, tracking moving targets, and conducting guidance and control of anti-aircraft and anti-missile weapon systems. In April 2022, the Institute of Atmospheric Physics at CAS and a space technology company, Beijing Xingjian Tianhang, were the first in China to successfully launch a rocket from a high-altitude, zero-pressure helium balloon in near space. The stated aim was physics research but the technology would also, in principle, allow other missile-like projectiles to be launched.

The balloon incident over the US serves as a reminder of the risks of international commercial collaboration with Chinese companies on dual-use technologies or technologies with potential military applications and underscores the need to step up IP protection. The recent history of Kuang-Chi is a revealing case study. The firm was founded by Liu Ruopeng after he was accused of stealing IP from a US Department of Defense–funded laboratory at Duke University. Reportedly, Kuang-Chi has collaborated with companies in the US, Canada and New Zealand.

In 2014, Kuang-Chi signed a memorandum of understanding with a New Zealand aviation management company, Airways, to test near-space flying platforms in New Zealand. The signing was witnessed by Xi and New Zealand Prime Minister Sir John Key (see figure 2). As agreed in the memorandum and a later contract with Airways, Kuang-Chi successfully launched China’s first near-space balloon flight in June 2015 from a dairy farm in New Zealand owned by a Chinese company, Shanghai Pengxin Group.

An Airways spokesperson told ASPI that ‘the contract with Kuang-Chi Science Limited was to provide air traffic control services for the launch of one test balloon from New Zealand in June 2015’ and that it has done ‘no subsequent work with the company’. The spokesperson rejected any characterization of the air traffic control service as ‘a collaboration with Chinese firms on dual-use technologies’. The testing of a launch capability for balloons is a necessary part of developing a balloon program. The data and experience collected from the New Zealand launch would have contributed in this sense to China’s military balloon program.

This underscores the need for governments, companies, research institutions and individuals to undertake due diligence when they are collaborating or contracting with foreign entities.

Source: Kuang-Chi, internet archive, 18 March 2015. Chinese President Xi Jinping is pictured on the left, followed by New Zealand Prime Minister John Key. Second from the right is Liu Ruopeng, chair of the board of directors of Kuang-Chi.

According to Sinologist Anne-Marie Brady—who has previously highlighted Kuang-Chi’s use of New Zealand for space launches—New Zealand has been one of many targets of Beijing’s economic and political influence in the Pacific to increase its clout and drive a wedge in the Five Eyes alliance (UK, US, Australia, Canada and NZ), among other reasons. New Zealand’s airspace is also relatively uncongested and the established infrastructure makes it an ideal place to test and launch near-space airships.

Increasing our understanding of Beijing’s capabilities is a top priority, but we also need to continue improving our understanding of Beijing’s strategic intent and the risks of international collaborations in bolstering China’s defence and security capabilities. Kuang-Chi’s apparent civilian collaborations and role as a supplier for Beijing’s military balloon program demonstrate how difficult it can be to assess technologies with potential military applications. This issue has caught out many companies and government officials over the years, including in Australia, Japan and the US. Our public and private sectors need to adapt and ensure the default is not to assist Beijing (or other authoritarian regimes) with dual-use development in critical technologies that affect our national security.

Tilla Hoja is a researcher and Albert Zhang is an analyst at ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre. Masaaki Yatsuzuka is a senior fellow at Japan’s National Institute for Defense Studies and a visiting fellow at ASPI.

This article appears courtesy of ASPI's The Strategist and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.