Sea Level Rise, Aquaculture are Making Bangladesh's Water Undrinkable

[By Riyan Sobhan Talha]

Twice a week, 50-year-old Brajasundari loads a collection of jerrycans onto a pedal cart, climbs aboard and travels three kilometres from her village Kanchrahati to buy water. Millions of women in arid and semi-arid regions of South Asia would call her lucky; they must do this twice a day, on foot. But Brajasundari lives in coastal Bangladesh, where there is water wherever you look – in ponds, streams, rivers and wells. However, it is all undrinkable.

Climate change has raised sea levels. The consequent ingress of saline water has poisoned freshwater sources throughout coastal South Asia. In Bangladesh, the salt water is seeping ever further inland.

So now Brajasundari travels to a shop where water is pumped up from a deep aquifer, treated and sold. This resident of Shyamnagar sub-district of Satkhira district, south-western Bangladesh, buys 60 litres of water on each trip, paying BDT 30 (USD 0.35) for the water and another BDT 20 (USD 0.24) for the pedal cart. The monthly expense of BDT 400 (USD 4.72) is over 10 percent of the average earnings of a landless agricultural laborer in this sub-district, going by the latest official statistics.

“I never thought that I might need to buy water for drinking,” Brajasundari told The Third Pole. “Earlier there were big ponds near our house. Everything is ruined by saline water. The problem of water is skyrocketing day by day.”

Back in 2011, a study led by Imperial College London and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine estimated salt intake from drinking water in Bangladesh’s coastal population exceeded recommended limits. Things have worsened since then.

Widespread problem

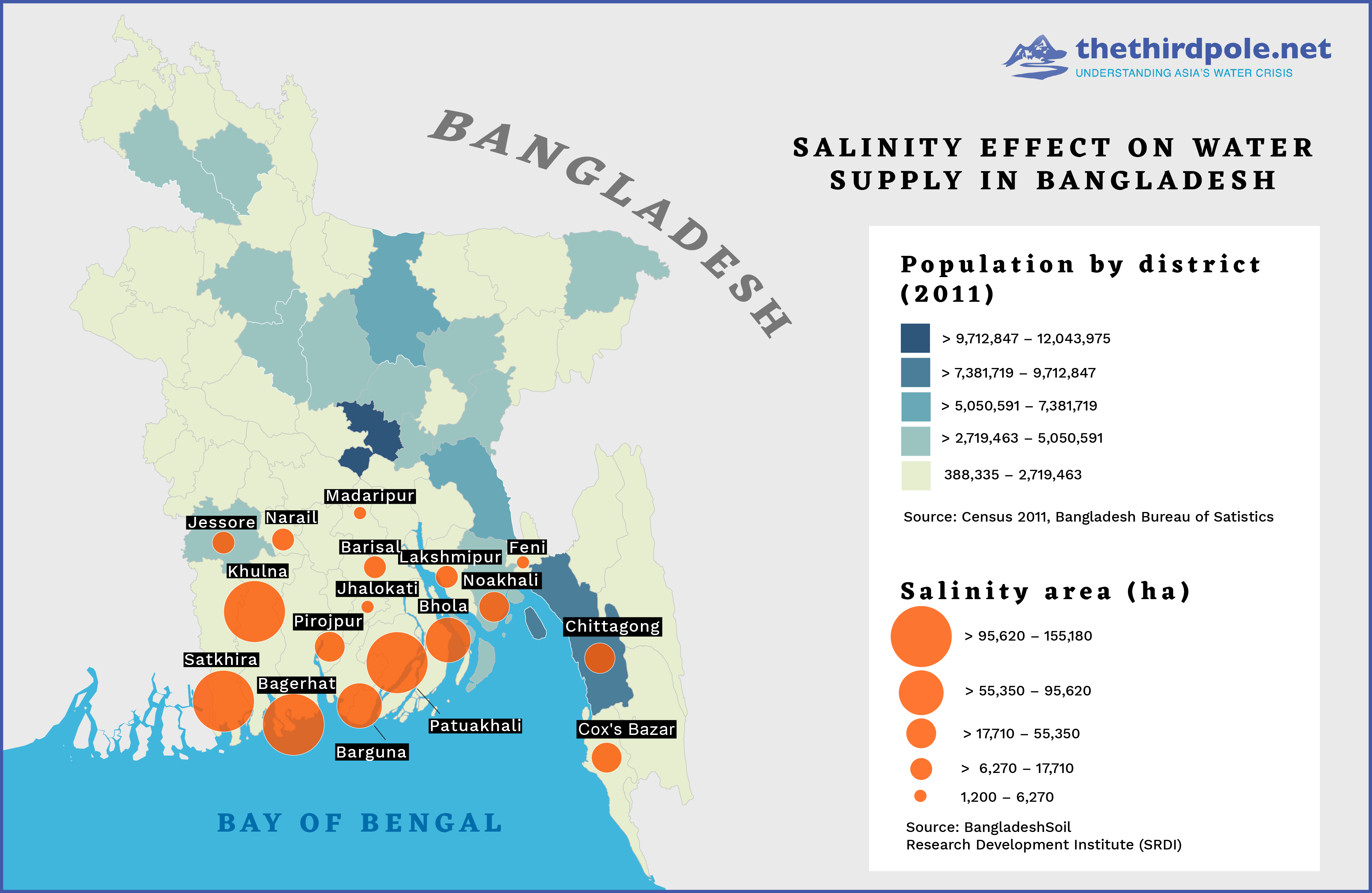

Satkhira is one of 19 coastal districts in Bangladesh and one of seven facing the Bay of Bengal. The coastal belt covers 32 percent of the country; over 35 million people live here, according to Bangladeshi government’s latest census.

Many studies have shown that people in coastal Bangladesh are suffering more and more as saltwater intrudes into their water supply due to climate change.

A 2014 World Bank report, River salinity and climate change: Evidence from coastal Bangladesh, forecast that by 2050 climate change will cause major changes in river salinity in the south-west coastal region during the October-May dry season. This will result in a shortage of drinking and irrigation water, with changes in aquatic ecosystems.

The water business

The shortage is here already. And all over coastal Bangladesh, it has spawned a new business: selling potable water.

A crowd in front of a water shop is a common sight nowadays. The shops are usually set up at points where relatively uncontaminated deep aquifers have been found. The water is pumped up, treated at a reverse osmosis (RO) plant at the back of the shop to get rid of the salt, and sold.

In the Nakipur neighborhood of Shyamnagar town, Shahinur Rahman owns such a shop, called the Mausumi Drinking Water Plant. He started the business in 2018 with an initial outlay of BDT 600,000 (USD 7,080). The RO plant can treat 1,000 litres of water per hour. He sells to 100-150 families every day, at 50 paisa (USD 0.0059) per litre.

“I earn BDT 40,000 (USD 472) per month,” Rahman told The Third Pole. “Selling water is big business here. People need it and we are just meeting the demand.”

Shahinur Rahman at his reverse osmosis water plant in Shyamnagar [Image by: Riyan Talha / The Third Pole]

Shyamnagar sub-district now has 25 RO plants for around 400,000 residents. All the plants are making money – hardly a surprise, since the residents have to pay more for water than residents in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. The Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority charges BDT 12 for 1,000 litres of water, while people in Shyamnagar pay BDT 12 for 24 litres.

Residents of the capital must install their own water-purification systems at home. Despite that, the cost of potable water for them is many times less than for people in Shyamnagar, where the average income per head is less than half of that in Dhaka.

A 2013 study by the NGO WaterAid Bangladesh said that the cost of potable running water in the coastal areas is far higher than in Dhaka. The study was conducted in two coastal districts, Satkhira and Khulna.

Aftab Opel, who led the study and now works at another NGO, Vision Spring, told The Third Pole, “The private water business on the coast is booming now. It’s increasing day by day. The price of water has come down per litre compared to 2013; but it is still several hundred times higher than in the capital.”

Illustration courtesy of The Third Pole

Local factors worsen climate change effect

The saltwater invasion of drinking water sources has been worsened manifold by commercial shrimp farming, which started in coastal Bangladesh in the 1980s. Shrimp farmers flooded plots of land with saltwater because shrimps grow best in brackish water. That saltwater has seeped into aquifers everywhere.

Dilip Dutta, a professor in the environmental science department at Khulna University, said, “Large ponds became undrinkable due to saline water intrusion. Shrimp traders have not taken any initiative to create new water reservoirs. They only care about profit.”

A 2017 study by Sebak Kumar Saha of Australian National University, called Socio economic and environmental impacts of shrimp farming in the south-western coastal region of Bangladesh, said, “Higher salinity levels in water sources due to shrimp farming have severe negative impacts on people’s health and wellbeing. Salinization of freshwater supplies due to shrimp farming causes scarcity of drinking water, as well as water needed for other daily activities such as bathing and cooking.”

Health impacts

While residents of coastal areas like Shyamnagar are forced to buy water for drinking and cooking, they cannot afford to buy more. As a result, the increasingly saline water is used for washing and bathing, with serious health impacts. Skin infections are common, as are urinary tract infections and pelvic inflammatory disease among women. Poor menstrual health is another huge issue.

People do not even drink as much water as they should. A 23-year-old resident of Jelekhali village in Shyamnagar sub-district said, “As water is scarce, I have to calculate before drinking it.” She works at a shrimp farm, spending the whole day waist-deep in brackish water. There is no drinking water at her place of work. In 2019 she went to a local doctor with a urinary tract infection. The doctor told her she was not drinking enough water.

Ratna Rani Pal, a worker at Shyamnagar health center, said, “Most of the female patients come to us with various reproductive problems. The reason is lack of care and management of menstrual health.”

Shampa Goswami, director of Prerona Nari Unnayan Sangathan – a women’s rights organisation in Kaliganj sub-district of Satkhira – said, “The lives of women here are under threat. The intrusion of salt water, climate change and one storm after another are making women’s lives miserable.”

Riyan Sobhan Talha is a Dhaka-based journalist and photographer. He reports on the environment, climate change and rights of indigenous communities.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

This article appears courtesy of The Third Pole and appears here under a Creative Commons license. It may be found in its original form here.

Top image: Water insecurity in coastal Bangladesh (courtesy Sonia Hoque / REACH / CC BY 2.0)

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.