In a Conflict With China, Carriers Might be Best Used as Decoys

[By Trevor Phillips-Levine and Andrew Tenbusch]

A large Japanese force emerged from the San Bernadino Strait, comprised of battleships and heavy cruisers, including the flagship Yamato. All that stood between them and the vulnerable U.S. landings at Leyte were the escort carriers, destroyers, and destroyer escorts of Seventh Fleet. Admiral Halsey’s Task Force 34 was ostensibly tasked to guard the San Bernardino Strait, a strategic approach north of the amphibious landings. But Halsey was then hundreds of miles away, steaming northward in dogged pursuit of a decoy Japanese carrier force. Urgent radio traffic from Commander Seventh Fleet did little to throw Halsey from pursuing the Japanese carriers until he received a pointed inquiry from Admiral Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas. The Japanese fleet successfully deceived Halsey and obfuscated their actual center of gravity for the operation by offering up some of their most prized assets as bait.

In chess, “The Queen Sacrifice” is well-known. The queen is one of the most important pieces and possesses wide mobility. In a queen sacrifice, a player risks their queen to gain a key advantage later, leveraging the perceived importance of the piece with their opponent. The U.S. Navy viewed its carrier forces as its center of gravity. If given the opportunity, the Japanese predicted that the U.S. Navy would pursue their aircraft carriers because the Navy would assume them to be similarly vital to the Japanese. Like chess, the battlefield is becoming an arena of persistent observation from robust satellite constellations. In a world of near-perfect information, deception becomes crucial, and the more believable the ruse, the higher the chances of success. Ruses can be made more believable by capitalizing on an adversary’s cognitive biases, such as their perceptions on what platforms are especially crucial to naval operations.

China already possesses the world’s largest navy, and the U.S. is unlikely to match China’s industrial capacity and speed in shipbuilding. Therefore, deterring and, if necessary, defeating China in naval combat will require deception to minimize U.S. vulnerability to the heavy attrition that can be quickly inflicted in a war at sea. For deception to be effective, the U.S. Navy must first be aware of how its enemies perceive its centers of gravity and then possess the willingness to use its prized assets in unconventional ways. Rather than try to force a traditional use case of the carrier onto an unprecedented threat environment, the Navy should consider novel approaches to carrier employment. Based on the currently limited reach of the Navy’s air wings, the carrier’s best use may be as a decoy force.

Enduring Truths

Since Fleet Problem IX in early 1929, the U.S. aircraft carrier has been recognized as an invaluable asset. However, surprise encounters with submarines and surface combatants revealed its vulnerabilities. The short range of the carrier air wings required the aircraft carrier to maneuver perilously close to the objective. Much depended upon accurate intelligence, the boldness of commanders, and luck. Some naval leaders remained unconvinced by tactics that placed the aircraft carrier at great risk. Others felt that the risk and loss of the carriers were completely justified if in the pursuit of “decisive” results.

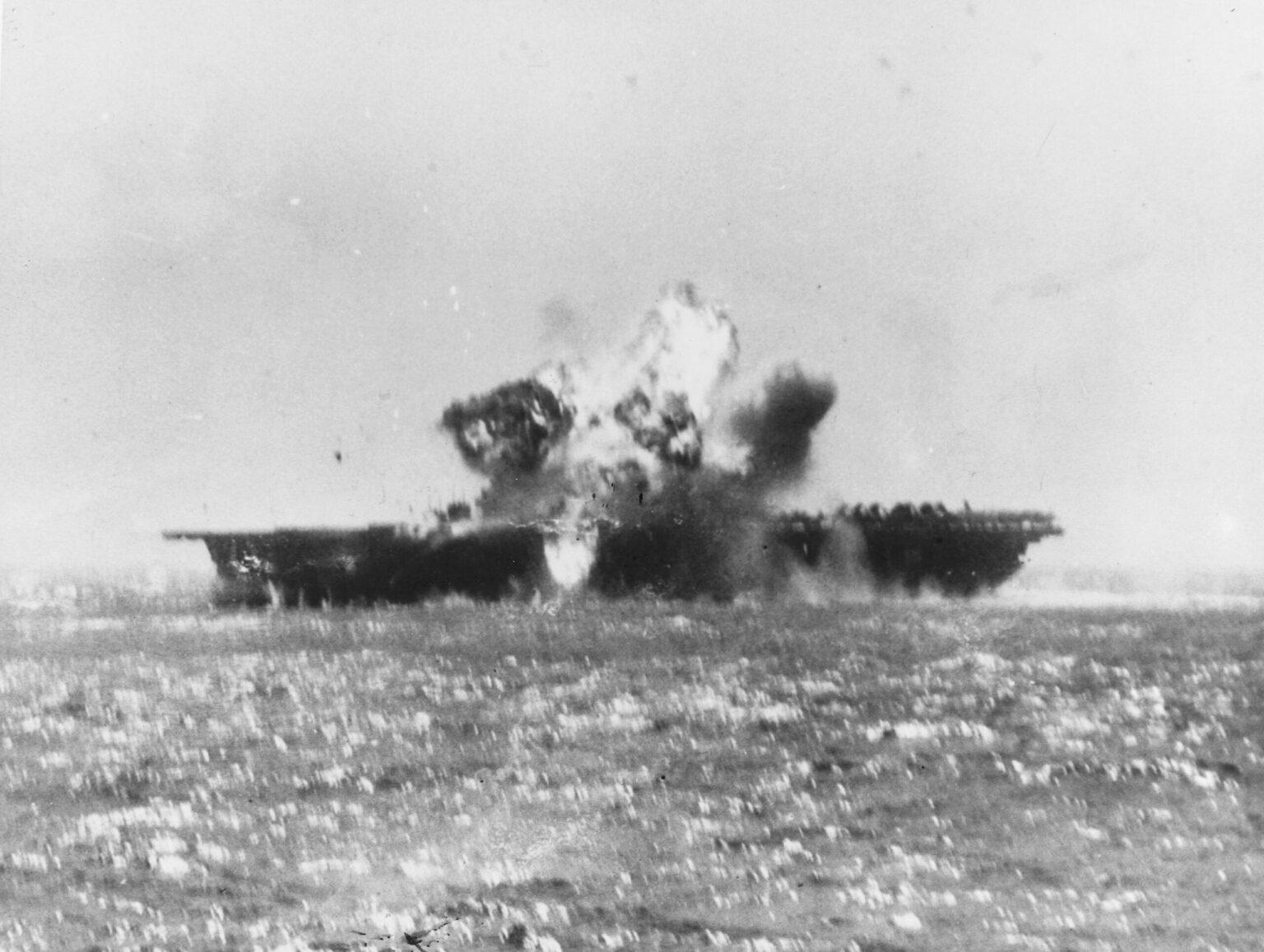

Fleet Problem IX and subsequent Fleet Problem exercises informed the development of U.S. carrier tactics for World War II. It also reinforced the desire among commanders to eliminate the enemy carriers first. Carriers remained vulnerable to shore-based air and susceptible to submarine attack. The debut of the missile age by the Kamikaze showcased the carriers’ vulnerabilities when forced within range of shore-based air and the difficulty of defending against guided munitions. By the war’s end, the U.S. had lost three escort carriers to Kamikazes and nine fleet carriers had taken Kamikaze hits. However, the fleet experienced greater losses among support and picket ships as they were often the first ships Kamikaze pilots would encounter.

The U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Essex (CV-9) is hit on the flight deck amidships by a Japanese Kamikaze, during operations off the Philippines, 25 November 1944. (U.S. Navy photo)

Submarines continued to be a persistent threat. During World War II, the Japanese lost eight carriers to submarines. The British lost five, while the U.S. lost four. Decades later, during the 1980s Falklands Campaign, the British deployed 11 destroyers, six submarines, and 25 helicopters to hunt down an obsolete Argentine submarine threatening its carrier task force. That Argentine submarine still managed to fire torpedoes against the British fleet and survive the war. Submarines present an asymmetric threat and are costly to defend against, requiring great resources to find and track. Over the years, the Navy hollowed out the carrier’s organic anti-submarine warfare capability, leaving the air wing dependent on inorganic assets like the P-8A Poseidon to find lurking submarines across wide areas. Yet these are assets that may not be able to follow the carriers into heavily contested seas, and and he effects of climate change will likely increasingly constrain detection ranges.

The threats to aircraft carriers are enduring and intensifying with technological advances. The necessity for carriers to maneuver within enemy weapon engagement zones to deploy offensive combat power has remained true for much of history, except in some recent regional wars. What has changed is that the carrier is less equipped to defend itself than in the past, and there is a perceived lack of willingness by U.S. leadership to stomach the loss of an aircraft carrier for the sake of employing its air wing.

Neutering the Aircraft Carrier

Symbols of American power projection, U.S. aircraft carriers prominently featured as American options for political messaging and de-escalation. President Bill Clinton dispatched two carrier strike groups to “monitor” saber-rattling after the U.S. approved a visa for Taiwan’s leader in 1996, during the “Third Taiwan Strait Crisis.” The dispatched U.S. carrier strike groups were to reassure allies and bolster regional credibility. At the time, a broad consensus existed that the People’s Liberation Army was “not in a position to take Taiwan.” The carriers’ successful interference in China’s campaign of intimidation against Taiwan during the crisis marked a seminal moment for the PLA. Since then, China has substantially improved its area denial capabilities, joint force integration, amphibious capability, and ocean surveillance. Today, analysts acknowledge that the People’s Republic of China is better positioned to mount an invasion – and threaten carriers – than at any other time in its modern history.

The People’s Liberation Army emphasizes neutering U.S. power projection capabilities by fielding precision weapons like the Dong Feng-21D and Dong Feng-26 ballistic missiles. Besides conventional strike capabilities for infrastructure targets (i.e., airfields or ports), the Dong Feng series of weapons also possesses maritime strike capabilities to target warships. The ranges of these weapons exceed the striking range of a carrier’s current embarked air wing. If the carrier is to utilize its striking power in a Pacific scenario, it must close to well within range of powerful shore-based capabilities.

The accuracy of long-range precision weapons depends upon extensive, over-the-horizon cueing networks and mid-flight retargeting capabilities. China’s long-range weapons are credible because of their supporting targeting infrastructure, including over-the-horizon radars, terrestrial and aerial surveillance assets, and satellite constellations. The vastness of the Pacific theater and the number of ships plying the ocean at any given time impart data processing delays, where analysis must sift through benign data and isolate contacts of interest. The speed of a decision cycle is referred to as the “OODA” loop, where a speed advantage relative to the adversary is a critical component of victory. Accelerating decision cycles will likely drive artificial intelligence integration, which can sift copious amounts of data at speeds and accuracy exceeding human analyses. China desires to lead in artificial intelligence, and reporting indicates that its military is heavily involved in its development. The PLA views artificial intelligence as key in “intelligentized” warfare environments and disrupting the decision-making pace of adversaries. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that China will likely mate its extensive ocean surveillance capabilities with artificial intelligence to sift through benign noise to find carriers and other warships.

Artificial intelligence may also be used to determine operational strategies. Some algorithm training sets use historical data. Historical data composed of human decision-making and behavior are imbued with human biases. These use cases can impart latent bias to the algorithm and, in the case of the U.S. carriers, potentially cause those algorithms to inherit an affinity for carriers’ centrality to U.S. naval operations. In fact, biases may manifest more significantly in algorithms, and humans’ trust in their output permanently skew their perceptions in future decision-making. Indeed, carriers played a central role in Japan’s naval campaigns before the Leyte operations, much as they did in the interwar period during the Fleet Problem exercises, reinforcing perceptions of their continued importance to Halsey. Artificial intelligence that learns from training data from the past 80 years of U.S. naval operations could develop similar perceptions and become self-reinforcing for human users.

Naval Deception

At the tactical level, paint schemes during both world wars on Allied shipping were designed to break up outlines, making identification and targeting by the enemy more challenging. New paint schemes on Russia’s Black Sea fleet may be an attempt to thwart target recognition algorithms and image-processing seeker heads. Other historical tactical deceptions took on more elaborate forms, as with Britain’s Q-ships during World War I. Masquerading as merchant ships to lure submarines to the surface, submarines were then ambushed by their not-so-helpless prey.

Today, arguments for the U.S. Navy to reintroduce decoys to divert attention and complicate surveillance are gaining favor. While China’s surveillance apparatus is formidable, it is finite, and each diversion or false target saps resources from finding the true one. The PLA’s weapon allocations are impacted by this uncertainty by tying down warheads. A weapon must be reserved for a perceived threat, eliminating it as an option for striking a different target. As such, fleets-in-being require considerable diversions of resources and capabilities kept in reserve, whether those fleets are a direct participant in an operation or not. For example, Ukrainian forces were forced to divert precious resources to monitor troop concentrations in Belarus and a Russian amphibious fleet in the Black Sea, despite the unlikelihood of either force launching a successful attack. Forcing China’s military to expend attention and munitions on ghost fleets and attractive diversions will be an essential element of operational art during conflict.

Magruder’s Principle is a concept in deception that states it is “easier to exploit the enemy’s beliefs than to alter those beliefs.”38 An enemy may be completely blinded by target fixation and confirmation bias if the deception is adequate. When Halsey pressed his attack against Japan’s carrier force, there were signs it was a diversion. Navy carrier scout planes reported empty flight decks and little fighter cover over the Japanese carriers, an anomaly that should have raised many red flags. But convinced of their importance, likely influenced by the carrier’s importance to him, Halsey continued his pursuit. And despite increasingly desperate radio traffic from the commander of Seventh Fleet, he remained convinced that the destruction of Japan’s carrier force took priority over all other efforts.

Japan’s desire to use the carriers as a decoy force may have stemmed from how their air wings were previously decimated in the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot” in the Battle of the Philippine Sea. There Admiral Spruance made a different calculation than Halsey, opting to shape the deployment of his task force in such a way as to give priority to protecting the beachhead rather than fully committing to a chase against Japanese carriers. The Japanese sent hundreds of their carrier aircraft into the teeth of American fleet defenses only to inflict negligible damage against U.S. capital ships. Unknown to the Americans, the massive losses they inflicted against Japanese aircraft removed Japan’s carriers as a credible force for the foreseeable future. When Japan opted to use its flattops as decoys, they were good for little else.

While there has been much contemporary debate on the survivability of the carrier, the Navy should also consider how the survivability of the air wing may affect future roles for flattops. An aircraft carrier is most vulnerable during aircraft launch and recovery operations when forced on predictable headings. To find a beehive, one needs only to find a bee to follow, a tactic Kamikazes used well by following returning Navy fighters. Unknown surface contacts that are launching and recovering multiple jet aircraft may strongly stand out against the backdrop of maritime traffic to an adversary’s ocean surveillance network. However, an aircraft carrier unburdened with flight operations is free to use a variety of frustrating tactics against the enemy. In either case, a diversion requires the devotion of more surveillance for increased scrutiny by the enemy, slowing their decision processes and diverting attention.

Overcoming the Institutional Barriers

Using the carrier in non-traditional ways, like a diversion in a deception campaign, will probably meet strong resistance within the Navy. The aircraft carrier remains one of the prominent symbols of American power and prestige. Despite the occasional essay questioning the value proposition of carriers in robust peer environments or advocating unconventional uses, the U.S. Navy overwhelmingly views its carrier fleet as its crown jewels. These viewpoints ossified after the end of World War II as the battleship’s fate had been sealed and the aircraft carrier took its place as the world’s premier capital ship. Over the decades, carrier aviators pervaded the Navy’s ranks and the halls of industry and government, cementing a strong advocacy network into place.

In 2015, former Navy captain and strategist Jerry Hendrix pointed out that some planners and leaders appear focused on protecting a traditional use case for the aircraft carrier and are not invested in war-winning strategies. Discussions and efforts to change the naval force through carrier reductions to fund alternative and likely more relevant and effective capabilities, like submarines, are met with stiff political resistance. If an adversary is aware of the herculean efforts the Navy will undertake to protect its most prized assets, then it has identified an exploitable vulnerability. Their assumptions and investments in fielding anti-carrier systems are correct and will always be cheaper and easier to deploy than the platform they target.

In chess, the objective is to capture the opponent’s King, not protect its queen at all costs. But there is evidence that is exactly what is occurring. Naval planners appear unwilling to consider a role for the carrier as anything other than the main effort of any naval campaign. Such closed-mindedness is unlikely to result in lucky outcomes, but rather short-sighted and costly sacrifices.

Japan’s decision to use its carriers as diversions was in accordance with Magruder’s Principle and preyed directly upon Halsey’s psyche. Before discovering the Japanese carriers, Halsey remarked, “If this was to be an all-out attack by the Japanese fleet [referring to attempts to disrupt the Leyte landings], there was one piece missing from the puzzle – the carriers.” While Campaign Plan Granite and Nimitz’s orders prioritized the destruction of the Japanese fleet, Halsey, ultimately pursued because these were important pieces – important because carriers were important to him. Admiral Kurita ultimately made the same mistake and shifted his focus toward the escort carriers that were near the path to his main objective because he mistook them for fleet carriers. Subsequently entranced by his own carrier target fixation, even when there was abundant evidence that he was not facing fleet carriers, Kurita wasted his opportunity to exploit the decisive opening the Japanese decoy carriers had created for him.

Winning is the main objective, not forcing a use case that does not conform to reality. To outsmart your opponent, one must first know how that opponent perceives your centers of gravity. U.S. narratives, writings, and real-world operations extolling the importance of aircraft carriers do much to reinforce the perception that these queens are the U.S. Navy’s prized possessions and that they will be the main effort for any coming maritime war. Navy commanders should be ready to exercise a break with precedent to exploit this narrative by entertaining the idea that the carrier might be better suited for other roles, especially as a decoy force. If not, they risk falling victim to their own mythology.

Trevor “Mrs.” Phillips-Levine is a U.S. naval aviator and a special operations joint terminal attack controller instructor. He currently serves as the Joint Close Air Support division officer at the Naval Aviation Warfighting Development Center and as an advisor for weaponized small drone development in a cooperative research and development agreement.

Andrew “Kramer” Tenbusch is an F/A-18F weapons system officer and a recent Halsey Alfa research fellow at the U.S. Naval War College. He is a graduate of the Navy Fighter Weapons School (TOPGUN) and previously served as a carrier air wing integration instructor at the Naval Aviation Warfighting Development Center.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

These views are presented in a personal capacity and do not necessarily represent the official views of any U.S. government department or agency. This article appears courtesy of CIMSEC and may be found in its original form (with extensive footnotes) here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.