Why do Beaked Whales Keep Returning to a Navy Sonar Range?

Scientists have determined that beaked whales prefer to feed within parts of a Navy sonar test range off Southern California that have dense patches of deep-sea squid and that these prey hotspots are needed to survive. Similar patches do not exist in nearby sonar-free areas.

For decades, the U.S. Navy has used high-powered sonar during anti-submarine training and testing exercises in various ocean habitats, including the San Nicolas Basin off Southern California. Beaked whales are particularly sensitive to these kinds of military sonars, which the researchers say have sometimes resulted in mass stranding events. Following legal action from environmental activists related to these risks, the Navy modified some training activities, created sonar-free areas, and spent more than a decade and tens of millions of dollars trying to find ways to reduce the harm to beaked whales and other mammals.

The new research, led by Brandon Southall at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and Kelly Benoit-Bird at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, set out to better understand why whales keep returning to the test range despite the risks.

The researchers equipped an underwater robot with echosounders to measure the abundance, density, and sizes of deep-sea squids in different parts of the Navy test range, as well as in nearby waters. They also developed an “energy budget” for beaked whales, showcasing the costs in time and calories of hunting for squid. This helped the researchers estimate how many dives the whales needed to make in order to get enough food to survive in different areas.

“Beaked whales work very hard to obtain their food. They are essentially living paycheck to paycheck,” said Benoit-Bird. Unlike many baleen whales with significant energy reserves, beaked whales can’t afford to expend too much energy on a dive that doesn’t result in capturing many squid. In areas where the concentration of prey is low, the beaked whales must work harder and expend more calories, making reproduction and raising young that much more challenging. Some of the areas under study were so poor in terms of prey that whales likely could not meet their basic energetic requirements if they only fed there.

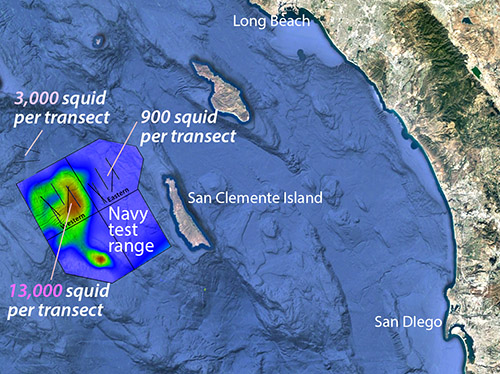

A portion of the Navy test range off Southern California encompasses one of these hot spots. Squid were 10 times more abundant in the area preferred by the whales. In this preferred area, the whales could get enough food by making just one dive a day. In a nearby sonar-free area (established with the idea that beaked whales could shelter in these areas while the sonar tests were underway) the whales would need to make between 22 and 100 dives per day to get enough food - something that would be difficult or impossible to do.

The large red area on this map shows where beaked whales congregate within the Navy sonar test range off Southern California. Data collected during transects by the REMUS AUV shows that deep-sea squid are much more abundant in this region than elsewhere. Base image: Google Earth.

This study is the first to link habitat quality with beaked whale behavior in such fine spatial scales. It also demonstrates that scientists can’t assess the quality of deep-sea habitats by simply making measurements at the ocean surface, or even by measuring the physical and chemical properties of the deep ocean. Direct measurements of the prey environment at the depths where animals are feeding, coupled with observations of when and where animals are foraging, are critical.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Until now, collecting such detailed data, even over small time and space scales, was virtually impossible. The researchers are now working on tools that will help them study predators and prey over longer time periods, and in other areas where the Navy operates high-powered sonar.

Similar field-research and modeling techniques could also be used to assess the potential impacts of other human activities that may disturb ocean animals, such as shipping traffic or offshore oil and gas development.