Vietnam and Cambodia Clash Over New Mekong Canal

[By Juki Trinh]

In August 2023, Cambodia sent an official notice to the Mekong River Commission flagging the construction of a new major canal project on the Mekong River. The Mekong, long a source of regional bounty, has become a modern point of contention for the countries along the waterway, with disputes over the environmental and economic cost to the river flow from the growing number of upstream dam and canal projects.

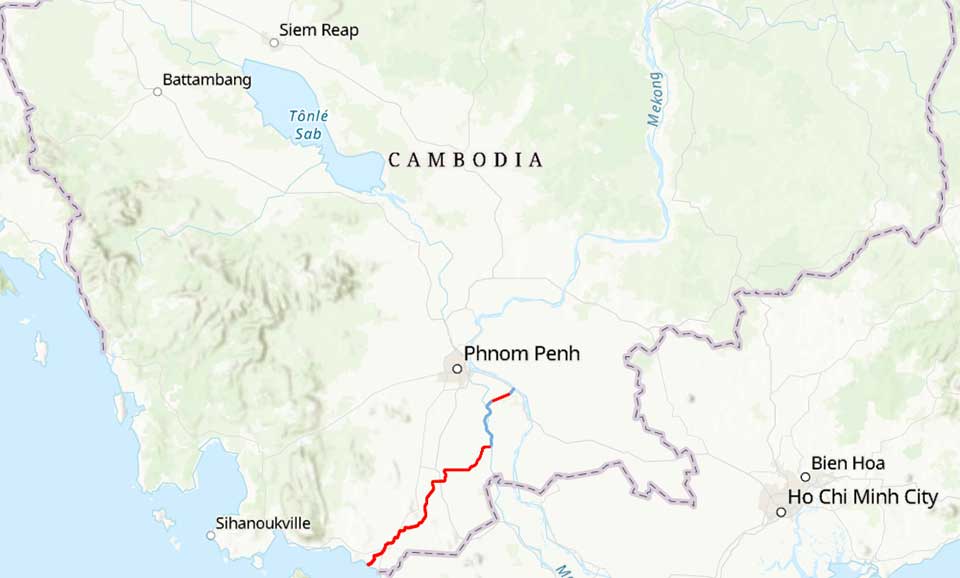

Cambodia’s planned 180-kilometre Funan Techo Canal, worth US$1.7 billion, is funded by China as a part of the Belt and Road Initiative. This canal provides a waterway linking the capital Phnom Penh and the deep seaport in the coastal province Kep, ultimately opening onto the South China Sea. The Cambodian government hopes that this ambitious project may foster economic development by facilitating the transportation of goods and eco-tourism, along with an estimated 5 million jobs to be created. Moreover, the Funan Techo waterway would reduce Cambodia’s dependence on Vietnam’s seaport, notably Cai Mep.

The canal project may bring economic benefits to Cambodia, however, it has lead to mounting concerns within neighbouring Vietnam. Water security is a particular concern, with the canal is thought to act like a dam, altering the flow of the river and preventing water from reaching areas in the Mekong Delta in the south of Vietnam. This would not only exacerbate the present long-term drought and growing problems with salination affecting Vietnamese agriculture, but also impact the habitat of endangered species.

Courtesy Cambodia National Mekong Committee

The project also brings geopolitical anxiety for Vietnam. The canal thought to have “dual-use” potential – that is, promoting economic growth and domestic connectivity for Cambodia, but it could also facilitate China’s military presence in the country. The canal is said to connect the Ream naval base in Sihanoukville, recently refurbished with Chinese funding. A CNN report in December last year showed that two Chinese navy frigates docked at the base. Security concerns have been raised about the ability of vessels to transit the Funan Techo canal from the Gulf of Thailand.

Cambodian officials have defended the aims of the project. Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Manet claimed the canal would have minimal effects on Vietnam and that there would be no foreign military base on Cambodia’s territory in line with Article 53 of its constitution. His father, and former Cambodian leader Hun Sen, declared the canal would not strain the Vietnam-Cambodia relationship. Meanwhile, the United States and Vietnam have called for more information and transparency about the canal.

The Funan Techo canal is a further example of Cambodia’s economic reliance on China and Beijing’s considerable economic influence in Southeast Asia. This concern is not only for Vietnam but extends to the unity and consensus of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. In 2012 and 2016, Cambodia blocked a ASEAN statement on the South China Sea dispute, which stymied Vietnam’s effort to internationalise the issue and call for regional support.

Hanoi’s influence in Phnom Penh has evidently decreased – a relationship that has a tumultuous history, with Vietnam having militarily intervened in Cambodia in 1978, maintained its influence in the country for a decade, and then significantly supported the Hun Sen’s government. Anti-Vietnam sentiment in Cambodia runs deep, as the stage for the clash of ancient empires seeking dominance in Indochina, with the Nguyen dynasty’s territory expansion southward over land regarded by Cambodians as “Kampuchea Krom”, and illegal Vietnamese migrants in Cambodia.

China describes Cambodia as its “ironclad” friend in Southeast Asia. The Mekong is watery thread that these regional rivalries are seeking to bend in their favour.

Juki Trinh is a PhD student at School of Political Science and International Studies, the University of Queensland. His research interests are Vietnam’s foreign policy, regional order change in the Indo-Pacific, and security studies.

This article appears courtesy of The Lowy Interpreter and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.