Tests Demonstrate the Potential of Autonomous Survey Drones

Last month, the NOAA Ship Thomas Jefferson integrated and operated a DriX, an Unmanned Surface Vessel (USV) created by the French technology company iXblue. The primary goal of the project was to test iXblue’s unique deployment and recovery solution specifically designed for Thomas Jefferson’s on board survey launch davit.

Survey launches are limited to daylight operations and deployment and recovery are the most challenging operations the ship undertakes. Utilizing a DriX for continuous survey operations without having to recover and/or service it for up to four days straight would significantly increase the ship’s efficiency.

There are a variety of USVs used for hydrographic survey operations. What makes DriX different is that it is designed by surveyors and is a proven packaged platform operating around the world. Jeremy McCaffrey, an iXBlue surveyor and DriX operator explained that, “Hydrographic charting surveys have been completed in the Hapai Group (Kingdom of Tonga) and Dusky Sound (Fiordland, New Zealand). Drix has also been used for a variety of different surveys from offshore wind farm inspections to safety of navigation surveys.”

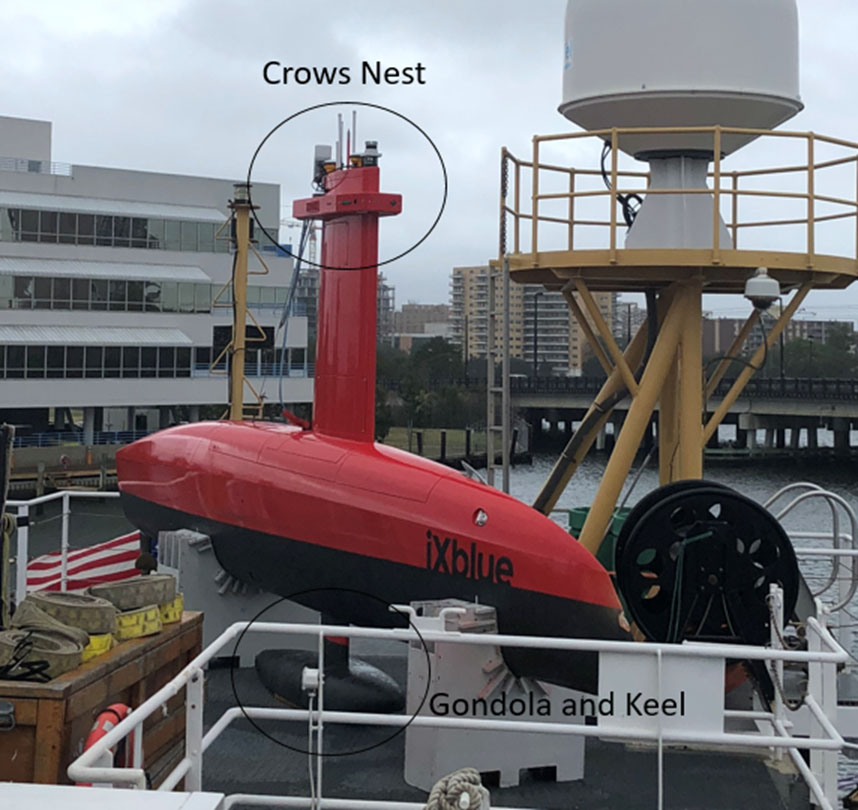

DriX is a 25-foot-long customizable USV that carries a multitude of survey sensors including a multibeam echo sounder and side scan sonar within its gondola. Before deployment, the team lowers the gondola and keel, giving the vessel about a 2-meter draft. The DriX carries a suite of sensors in its crow’s nest, including lidar, cameras, data radios, and its own position and orientation system. The automatic detection system, which uses an onboard lidar system, helped the vehicle avoid obstacles (including a curious seabird) during testing.

DriX resting aft on the second deck of NOAA Ship Thomas Jefferson. (Lt. Cmdr. Damian Manda)

The DriX operates remotely, autonomously, or semi-autonomously. When running remotely, an operator uses a hand remote control box to pilot it. The DriX has two different modes for communication, Wi-Fi and marine broadcast radio (MBR). For normal survey operations, the DriX uses MBR for long-range communication up to 18 kilometers from the ship. The MBR is located on the mast of the ship, which creates a 400-meter dead zone in the immediate vicinity, necessitating the use of the Wi-Fi connection for deployment and recovery.

Thomas Jefferson crew practicing emergency tow. (Erin Cziraki)

DriX deployment and recovery

iXBlue designed the DriX Deployment System (DDS) similar to the ship’s own launch deployment system. In order to deploy the DDS in the water away from the hull of the ship, iXBlue set up a unique boom system on the starboard side. The boom system resembles the mast of a recreational sailboat, complete with block and tackle for adjusting the tow point of the DDS. Before deployment, the operator lowers the rigging system so the boom is perpendicular to the ship and as low to the water as possible. The lines are tightened to point the bow of the DriX toward the ship and the stern away from the ship for better exit clearance.

Lt. DeCastro supervises the launching of DriX under way from the DDS. Credit: Ens. Taylor Krabiel

DriX about to exit the DDS with the “latch” and “hoop” open. (Erin Cziraki)

Once the DDS and DriX are in the water, an operator on deck remotely activates two latches on the DDS to free the DriX. Once the DDS ‘arm’ and ‘hoop’ are opened, the pilot drives the DriX away in Wi-Fi mode. Recovery of the DriX is the reverse of its deployment, with the latches on the DDS used to lock it into place prior to lifting it out of the water.

For the crew, this evolution was initially the challenging part of testing. However, the team adapted to this unique operation after many hours of training and practice. In trying different approaches to this new method of deployment and recovery, the ship’s crew was able to improve and streamline the process.

DriX operation

Integrating the DriX into ship operations has been a change of pace for the entire crew. Typically, when the ship has a launch in the water operating independently of the vessel, it will have crew onboard to manage vessel traffic. However, unlike the launches, the DriX does not have the ability to self-manage traffic. The best way to track the DriX and maintain situational awareness of its location relative to the ship and nearby traffic is through the human machine interface or HMI. The HMI is a screen that shows what lines the DriX is currently surveying, how far away the DriX is from its mothership (i.e. Thomas Jefferson) and other vital information related to how the DriX is operating. The DriX operator and those on the ship’s bridge use the HMI so all parties have situational awareness of the DriX.

DriX operators driving DriX in WiFi mode from the survey room onboard the Thomas Jefferson. (Cmdr. Briana Hillstrom)

Communication among the bridge team, the DriX operator, and Thomas Jefferson’s survey watch stander is essential to understanding where each vessel is operating and collecting data in the survey area. Whenever the ship is changing speed or course, the DriX team is informed, and whenever DriX is making changes to its speed or course, the bridge team is informed.

In several circumstances where the DriX became disabled, Thomas Jefferson tended to the DriX while deploying a small boat for recovery. This happened twice while the ship was underway, but both times the disabled DriX was safely recovered.

FRB recovery of the DriX. Credit: Lt. Cmdr. Meghan McGovern

DriX test results

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

Overall, the testing of DriX had its ups and downs. DriX was disabled in the water a few times, however, it was generally easy to recover as the iXblue team and the ship’s crew worked hard to ensure the DriX was operational as soon as possible. One of the highlights was observing DriX’s efficiency in collecting high quality multibeam data, increasing the overall operational efficiency of the ship significantly. It is a new and exciting tool for surveying that offers different challenges and benefits for Thomas Jefferson. While it is sad to say “bon voyage” to the DriX and its crew, we know that this experience has improved the understanding of these operations and shows promise for the world of hydrography as a whole.

This article appears courtesy of NOAA and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.