Stress Is Not Always a Bad Thing - Until It Is

Editor's note: This essay was originally published in 2021, but it has new relevance given the number of U.S. Navy ships operating under fire and engaging threats daily in the Red Sea. It is reprinted here with the permission of the author and USNI, and it may be found in its original form here.

The approach to the replenishment ship was going badly, and as the commanding officer, I sensed some of the precursors of a mishap. A material deficiency in the fuel line that necessitated a different configuration than normal, a brand-new conning officer, and an early morning event after a long night should have been enough to tell me that something was not right. The night before, I discovered that my wife back home in Norfolk had fallen and suffered a concussion and two broken arms. In typical SWO fashion I told no one, and decided that focusing on the mission and “compartmentalizing“ my personal issues was the best approach. In doing so, I set myself up for what happened next. Through a series of small mistakes we slowly closed to distance from 200 feet to 100 feet to 50 feet before the noise and commotion snapped me out of my funk—and I ordered all ahead flank and an emergency break away. A $1 billion warship came within three feet of disaster because one person failed to recognize and mitigate the signs of stress and fatigue and their impact on operations—me!

Later on in my tour, after a visit from the Operational Stress Control team, I learned a few things about stress and myself. I learned that not all stress is bad; sometimes a lack of stress can lead to boredom and complacency; a bit of fear raises the stress level and makes you think more clearly and focus—it’s not a bad thing (think of Tom Brady the night before the Super Bowl when everyone has decided his time as GOAT is over!). But that is different than when you find yourself on the right side the operational stress control curve where, as I now know, you are “injured” or “ill, ” per figure, and no longer in a position to help yourself solve a stress related issue alone. I know; I have been there.

Figure 1. The Navy’s Operational Stress Continuum shows the impact—and responsibility for mitigations—of the full spectrum of stress as it impacts sailors.

What did I do wrong that day? First of all, I failed to recognize how fatigue and stress affected my ability to function. Like alcohol, the effects of fatigue and stress directly affect an individual’s ability to recognize how they are impacted by it. This is the first module of the Operational Stress Control course, and probably the most important. Second, I failed to talk to someone who could help me work through my problem. I had a chaplain, an executive officer, and a command master chief that could have provided backup and guidance to help me get “back to Green.”

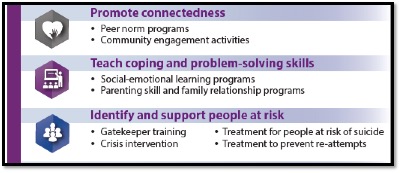

Buddy care is another module in the expanded Operational Stress Control course. This incident occurred before I started my decades-long study of the effects of fatigue but I certainly saw it that day—and learned the hard way how the loss of even one night’s sleep can directly affect decision making, something I later learned in the “fatigue management” model. Having spent a lifetime solving problems as a naval officer, I thought I had that part down pretty good until I sat through the problem-solving module in which the instructor laid out a very simple, common-sense, step-by-step approach to write down problems, work through solutions, and find ways to mitigate the stress that you have now been able to recognize in yourself and others. Some of these methods to help yourself and others are listed in figure 2 below:

Figure 2. Expanded operational stress control will address several tenets of the CDC’s key processes that support suicide prevention and destructive behavior—excerpt shown here (Source: www.cdc.gov).

In 2017, I penned an article in which I decried the Navy’s decision to stand down the Operational Stress Control team and predicted that the results would be visible. It is impossible to show causality, even correlation, to any given metric based on one program, but based on feedback from the fleet, and as the surface navy discovered when it eliminated Surface Warfare Officer Basic School, (channeling Joni Mitchell), “Don’t it always seem to go, that you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone.” So Operational Stress Control is back with a different model that eliminates some of the challenges of the original program such as time, schedule, travel, and logistics.

The new “expanded” course (EOSC) is taught to volunteer facilitators in a two-and-a-half-day virtual class that provides the tools and techniques to implement the ships program. Speaking of stress, it is likely that a year of COVID would have shut the program down anyway and called for a solution like the one currently being rolled out. I attended the course in October of 2020 and found it very enlightening, professional, and practical—I am already putting some of the concepts to use in my day job and at home, and it is working for me! It also is worth noting that this program is part of the overarching Chief of Naval Operations Culture of Excellence initiative that includes Warrior Toughness training at accession points and several other areas that focus on toughness and resiliency.

To date, several ships have been inducted into the pilot program. One as a mitigation for a high-stress “double-pump deployment” over the holidays after a record-setting deployment with no port visits, the others as they come out of a multiyear shipyard maintenance period returning the crew back to an operational schedule. Initial feedback from these commands is positive, as they apply the lessons of the EOSC program, but as with all new processes, we are already learning. A few lessons have already come to light it worth sharing:

- Education is essential. Starting immediately, commanding officers, executive officers, and command master chiefs should receive an overview of the program during pipeline training.

- Active support is necessary. A quick meeting between a knowledgeable coordinator and the command triad to outline the program and how it will be implemented to their specific ship needs and to answer questions is critical. Without triad buy-in, the program will fail.

The next most important thing is picking the right people. This is not a collateral duty for the random chief who takes over for the guy or gal who had it before. As an executive officer called in my Navy-Marine Corps relief society representative, a division officer, to ask him why our numbers were so poor compared to the fleet. He said “Sir, as I told my department head, I am morally opposed to charity and I was a bad choice to run this program but it was my turn.” Oops! The point is this: Operational stress control should be taught by someone who is willing to stop and listen and not simply pontificate and provide answers or read from a PowerPoint deck.

Institutionalizing the process as a complement to other programs, vice simply another “requirement“ is critical. The chaplain, the command resilience team, suicide prevention, and drug and alcohol prevention coordinators could all be a bit less busy with an EOSC program that addresses the “left side” of the stress continuum.

As I wrote in a recent article, my return to the surface Navy after a six year hiatus has been a stressful event in my life, and I described some of the mitigations being implemented. Personally, I believe U.S. forces are more stressed operationally today than they were when I retired in 2013. Double-pump deployments, gaps at sea, cross decks, hyper-extended maintenance periods, and the multi-layer impact of COVID on families, duty sections, and even under way watch bills, have only begun to be calculated in terms of lost man days.

Some would argue that there is a difference between work-related stress and “personal” or family-related stress. I disagree. That day, on the bridge of the USS San Jacinto, the two lines crossed with nearly disastrous results. Bottom line: Unplanned losses of any form that stem from mental health issues affect not just the individual, but his or her ship at a divisional, watch bill, and ship-wide level.

that matters most

Get the latest maritime news delivered to your inbox daily.

A final point: as much potential as EOSC shows, it is a mitigation that does not directly address root causes. As one mental health provider so aptly put it, “I can step up my game as a fire fighter, but y’all need to stop lighting fires.“ It is my fervent hope—and belief—that the Navy will continue to address potential root causes of operational stress with continued initiatives to stabilize ships’ schedules, shorten maintenance periods, and fully man ships throughout the Optimized Fleet Response Plan. Until it does, the EOSC program not only is a welcome step in the Navy’s trend toward enhanced “people-centered” leadership, but a necessary one.

Captain (retired) John Cordle completed two Navy surface ship command tours including a wartime deployment in command of USS Oscar Austin (DDG 79) and a counter-piracy deployment in command of USS San Jacinto (CG 56). He was awarded the Navy League John Paul Jones Award and the Bureau of Navy Medicine Epictetus Award for Innovative and Inspirational Leadership for his work in crew endurance and circadian watch rotations.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.