Grand Finale for Infamous Glomar Explorer - Part 1

The ship that secretly raised a Soviet submarine is being scrapped

The story of the Glomar Explorer spans four decades and involves a Soviet nuclear missile submarine, the CIA and an eccentric billionaire. The tale is worthy of a Hollywood blockbuster, but the real-life story of the Glomar Explorer eclipses any fiction Tinsel Town could concoct.

The vessel’s history is steeped in international intrigue. The $350-million drillship – an engineering marvel that was far ahead of its time – was built for Global Marine, a company owned by Howard Hughes, the eccentric American businessman. It was supposedly to be used to extract manganese nodules from the ocean floor and was constructed at Sun Shipbuilding and Drydock (remember Sun Oil Company – Sunoco?) in Chester, Pennsylvania. Its maiden voyage took place on June 21, 1974.

Over the years, Global Marine executives and others have testified in federal court that the Glomar Explorer wasn’t really built to mine manganese but was designed and constructed specifically to get something much most precious to the U.S. off the seabed.

(K-129 original video montage image. Courtesy of filmmaker Michael White)

(K-129 original video montage image. Courtesy of filmmaker Michael White)

Project Azorian was the code name for the covert CIA project whose real goal was the recovery of a Soviet nuclear missile submarine, which was lost in 1968 about 1,500 nautical miles northwest of Hawaii. The U.S. Air Force had captured sonic recordings of an explosion that took place on March 8, 1968. Subsequently, it was able to localize the latitude and longitude of the Soviet submarine, and the U.S. Navy conducted a deep-sea reconnaissance mission that took over 20,000 photographs of the sunken Soviet K-129 submarine.

President Nixon and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger approved the mission, which created significant engineering challenges as the 2,000-ton submarine lay at 17,000 feet on the ocean floor. At the time, the deepest-ever salvage operation had taken place at a mere 245 feet and recovered a satellite bucket weighing only a couple of hundred pounds.

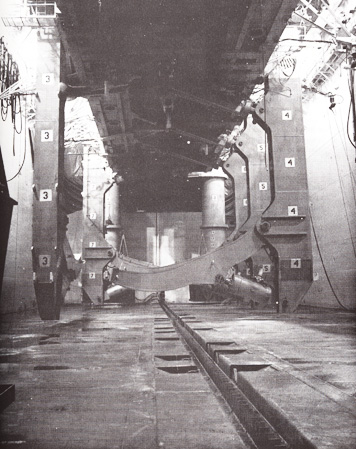

In order to carry out the mission, a massive claw-like apparatus was built by Lockheed to fit the sub’s exact specifications. It was affectionately called “Clementine” and weighed 2,170 tons and consisted of two steel beams that were 179 feet long and 31 feet wide.

The Glomar Explorer itself was 618 feet long with a 115-foot beam, which was too large to transit the Panama Canal. So after sea trials it began its long voyage on June 21, 1974 around South America to Long Beach, which included a stop at Valparaiso, Chile to collect a few more Global Marine employees.

The evening before the ship was scheduled to arrive in Chile, a military coup overthrew the government. There were 178 people onboard the vessel including the crew and members of the CIA. It sailed out of port without incident, but it was a close call just the same.

The U.S. Navy had used a large network of hydrophones, which can distinguish military ships and submarines from ordinary maritime traffic, to locate the K-129 on the ocean floor. The camera onboard a Navy ship showed that the submarine had broken in two pieces. It was assumed an explosion took place as the sub was recharging its batteries, which give off hydrogen gas, and was most likely ignited by a spark from the engines.

The Glomar Explorer finally reached its destination on July 4, 1974, but inclement weather delayed the salvage operation for several days. Around the same time as the recovery cage was being lowered into the ocean, the Soviet warship Chazhma arrived on the scene carrying a Kamov Ka-25 helicopter. A Soviet naval tug arrived as well to help in monitoring the U.S. ship’s operations.

(Computer Generated Image of Recovery Operation. Image Courtesy of filmmaker Michael White)

(Computer Generated Image of Recovery Operation. Image Courtesy of filmmaker Michael White)

The Glomar team had to carry on its operations with the Soviet Navy watching. To prevent the Soviet helicopter from landing onboard, boxes were stacked on deck, but what caused the most anxiety during the operation was debris that might float to the surface once the sub was lifted off the ocean floor.

Such a disaster almost took place on August 4 as the sub was being raised. At about 6,700 feet, the crew noticed that two-thirds of the vessel had broken off and only about 38 feet were left in the claw. On August 9, the same day that Richard Nixon resigned as President, the CIA and Glomar team lifted the remains of the sub into the ship’s gigantic moon pool.

As the CIA inspected the wreckage, several important documents and manuals were recovered. But the most pressing issue was the discovery of several bodies of the 98 crewmen who died in the sub’s explosion. While three of the crew members were identified, the rest were not. By September, all of the bodies were recovered and were buried at sea with full honors.

Image of the “Hughes” Glomar Explorer in Long Beach 1974. Image Courtesy TedQuackenbush (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Image of the “Hughes” Glomar Explorer in Long Beach 1974. Image Courtesy TedQuackenbush (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

The Glomar Explorer returned to Long Beach in September 1974 with a number of crates recovered from the sub. The sub itself was transported to the naval submarine base in Bangor, Washington. But the CIA wanted the rest of the vessel that remained on the ocean floor.

Operation Matador was now in play, but the media found out about the secret mission and the story became front-page news. The Soviet Ambassador to the U.S. demanded an explanation from the Ford Administration. While Secretary of State Henry Kissinger did not admit what the operation was about, the plan to recover the rest of the sub was scrapped.

In 1976, the U.S. General Services Administration considered leasing the Glomar Explorer, but the deal never came about. In September of that year, the U.S. Navy acquired the vessel, which was added to its auxiliary operations. The ship was laid up in Suisun Bay in the San Francisco Bay area but was kept a safe distance from other laid-up ships due to concerns about residual radiation.

To read the article’s conclusion click here for Part 2

This article features writing contributions from Wendy Laursen and Kathryn Stone.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.