U.S. Sets Out 150 Oil Spill Research Priorities

The U.S. Interagency Coordinating Committee on Oil Pollution Research (ICCOPR) has approved the Oil Pollution Research & Technology Plan (OPRTP) for FY2015-2021 and selected 150 priority research needs that should be addressed to improve oil spill management.

The report sets out the current state of research and examines key events, such as Deepwater Horizon, where lessons have been learned. It also covers research needs for better understanding of Arctic operations. Some of the incidents examined in the report include:

M/V Selendang Ayu

During a large storm in December 2004, the M/V Selendang Ayu, carrying a cargo of soybeans, lost power and grounded on the west side of Unalaska Island, Alaska, where it broke into two and released 337,000 gallons of IFO-380 fuel oil, marine diesel, a small amount of lube oil as well as its soybean cargo.

Response measures included employing SCAT, an assessment process used for all spills where shorelines are impacted, and manual shoreline cleanup. The potential of an additional release from the floating half of the vessel triggered testing and approval for dispersants and in situ burning (ISB), which were not employed.

After the initial response, cleanup was halted until April 2005 due to deteriorating winter weather conditions. In the spring, most shorelines were manually cleaned and dry mechanical tilling and berm relocation techniques were used where appropriate. Response actions continued during the weather-permitting seasons until June 2006.

This incident highlighted the difficulty of response operations in the Arctic environment and the availability of suitable response technologies in cold, icy conditions. The After Action Review for the M/V Selendang Ayu incident discussed the following specific R&D needs (Wood & Associates, 2005):

• improve information sharing, including identification of response equipment and resource availability.

• develop methods to determine the transportation and fate of oil in Arctic waters.

• develop measures of containment for application in Arctic conditions.

• develop technology improvements for Arctic shorelines and weather conditions.

Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill

In April 2010, an estimated 205.8 million gallons of oil began flowing from a subsea well blowout that followed an explosion and collapse of the Deepwater Horizon platform.

Response to the Deepwater Horizon spill was diverse and conducted on a larger scale than any previous efforts. Different response mechanisms were deployed depending on the day, the weather conditions, and the amount and location of oiled shoreline. This included: subsea and surface dispersant use, booming, and skimming. Application of 1.84 million gallons of dispersants, both aerially and sub-sea at the wellhead, was unprecedented, as was the use of controlled in-situ buring (a global record of 411 individual burns were conducted).

This spill was the first where dispersants were applied subsea at the wellhead. Existing options failed to satisfy the public expectations, which led to the testing and evaluation of more than 120,000 response technologies through the Alternative Response Technologies Evaluation System (ARTES) Program.

The incident report (USCG, 2011) highlighted the following R&D needs:

• ensure minimum standards and consistency for Gulf of Mexico Area Contingency Plans (ACPs).

• identify Environmentally Sensitive Areas (ESAs).

• develop improved technology and response protocols for well blowouts.

• develop systems to better meet the needs of oil spill response organizations.

• establish standards and processes for rapid collection, processing, correlation, analysis and distribution of satellite imagery and oil thickness sensors to direct spill response operations with real-time data.

• develop improvements for subsea oil detection.

• develop and use enhanced SMART monitoring technologies and protocols in offshore environments.

• develop technology to determine oil slick thickness.

• develop improved and more efficient skimmers and mechanical recovery equipment.

• use a fully operational Common Operating Picture (COP) available during drills, exercises, and actual events.

• develop protocols for thorough, independent testing and evaluation of response technologies prior to being used on a spill.

• study the toxicity of dispersants as a function of oil and dispersant types, and different environments.

• study dispersant efficacy including volumetric limitations of applications.

• study dispersant efficacy in mitigation of environmental impacts.

• develop methods and programs to monitor and track large, dispersed oil plumes.

• conduct a case study analysis of all aspects of dispersant use including environmental effects of dispersants and dispersed oil.

• study the effectiveness of dispersants under different environmental conditions (e.g., subsea).

• study where ISB can be used as a response option and areas where it can be subject to expedited approval.

• study the performance of various fire boom designs and improve technologies for water-cooled and reusable booms.

• develop outreach programs for, and incorporate state and local emergency managers into, spill preparedness and response.

• Spill of National Significance (SONS) doctrine should be adapted to be more inclusive of state, local and tribal governments in a response.

Improved Response

"The research needs focus on the tools and technologies employed by the Coast Guard On-Scene Coordinators to address oil spills in the marine environment," said Bill Vocke, who works for the Coast Guard's incident management and preparedness policy directorate and also serves as ICCOPR’s executive director.

"Addressing these priority needs will not only improve our capabilities to respond to spills but also improve prevention, preparedness and injury assessment/restoration capabilities," said Vocke.

The committee intends to update the plan every six years to reflect advancements in oil pollution technology and changing research needs.

However, the U.S. Coast Guard notes that the plan does not establish any regulatory requirement or interpretation, nor does it imply the need to establish a new regulatory requirement or modify an existing regulatory requirement.

The plan is available here.

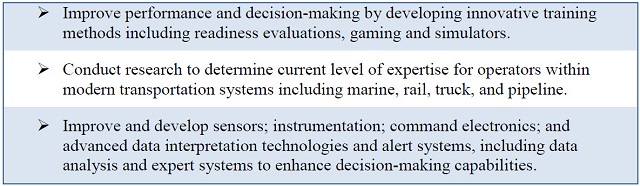

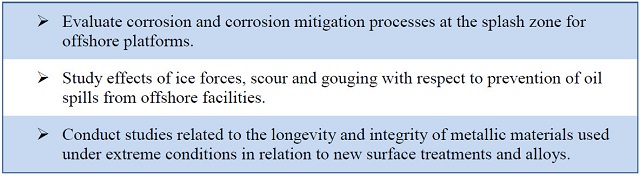

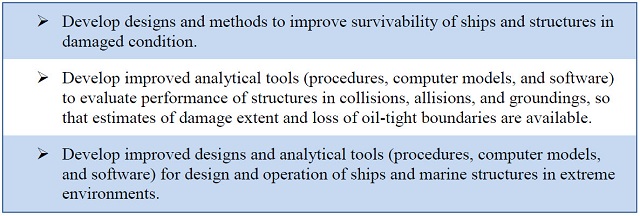

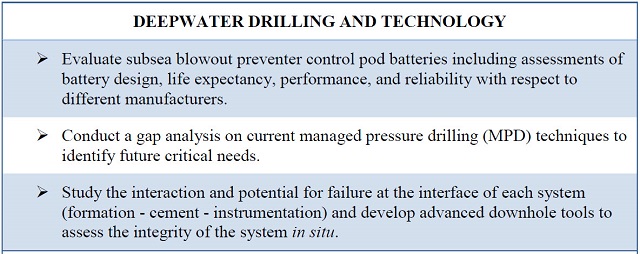

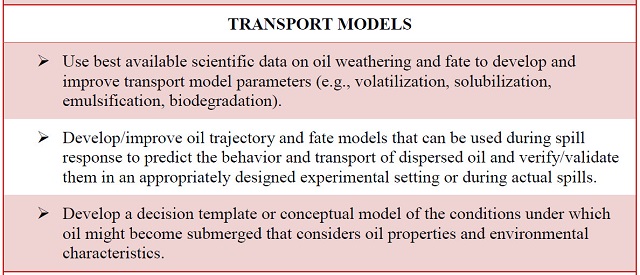

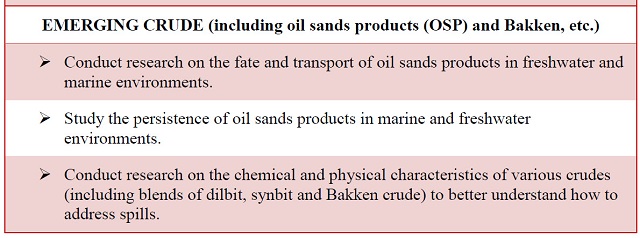

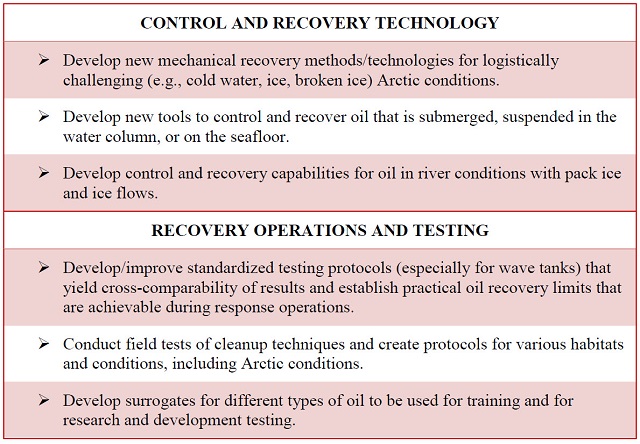

Some of the research priorities announced