[Photos] Weathering Change in the Arctic

The Russian icebreaker Vaygach recently completed a transit of the Northern Sea Route in just seven and a half days. Although it was hailed as a new record by some Russian media, it is the time the transit was made that is perhaps of greater significance.

The Vaygach, a nuclear-powered icebreaker, left from the Siberian side of the Bering Strait on December 17, covering more than 2,200 nautical miles before reaching the White Sea on December 25.

The vessel’s average speed during the transition was more than 12 knots, and the trip was made more than a month after the shipping season usually ends in the Arctic. Other transits are said to have been quicker – but in mid-summer rather than that time of year.

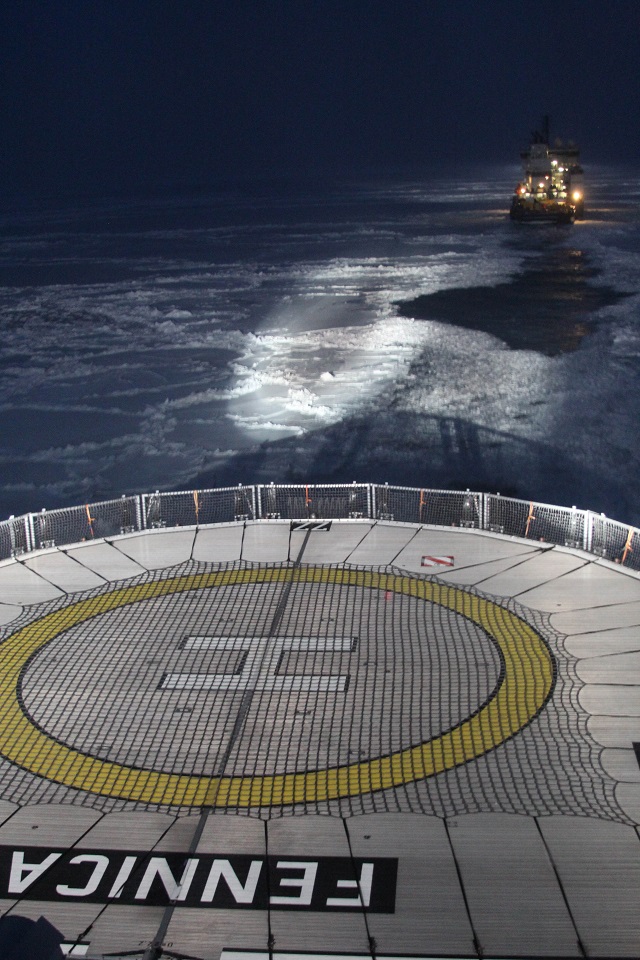

The timing of the trip is seen as an indication of changing ice conditions in the Arctic, a phenomenon that extends beyond the Northern Sea Route. Captain David “Duke” Snider transited the Northwest Passage on board the ice breaker Fennica in late October and early November after sailing the Arctic virtually non-stop on various vessels from July. Snider is an ice navigator and master with around 30 years at sea, CEO of Martech Polar Consulting and author of the book Polar Ship Operations.

“During this long summer at sea, I saw heavier ice than usual off the east coast of Baffin Island in July and August,” says Snider. “I saw huge open water expanses north of the Yukon/Alaska border in regions normally well encumbered by ice, but at the same time a polar pack ice edge further south that we have seen in the last few years north of Barrow and the Alaska North Slope.”

Snider believes his journey on Fennica may have been the latest transit of the Northwest Passage ever. The vessel never used more than 50 percent of its power, and its average speed was about 12 knots. Fennica was slowed northbound in the Bering Sea by heavy weather, which is normal, but made a transit in what amounted to only new ice until it encountered some multi-year ice at the eastern entrance to Lancaster Sound.

“The bottom line is, global climate change is real, sea ice in general is indeed decreasing in extent, but it is still there, and it still moves about in many ways unpredictably,” says Snider. “Weather events MAY be getting more extreme, but that does not concern me as much as the variability in ice conditions. What was good yesterday is bad today, and that holds true weekly, monthly, annually and across decades. If you venture into the Arctic expecting a summer cruise with no issues you are sadly mistaken.”

Snider has worked on board the Japanese research vessel Mirai in both the 2013 and 2014 seasons. The vessel conducts research into Arctic weather and how it can affect the mid-latitudes.

Some of the research has just been published. Dr Jun Inoue, from the National Institute of Polar Research in Japan, and his team have published a paper: Additional Arctic observations improve weather and sea-ice forecasts for the Northern Sea Route in the journal Scientific Reports.

Inoue states that the current reduction in Arctic sea-ice extent causes unpredictable weather phenomena in the Arctic Ocean (strong winds, high waves and rapid sea-ice movement associated with cyclones) and also over the mid-latitudes (heat waves and severe winters). With such changing background conditions, more accurate weather forecasts are needed to safely navigate along the Northern Sea Route and to understand the climatic linkage between the Arctic and the mid-latitudes. However, this is difficult because of the sparse number of atmospheric observations across the Arctic Ocean.

The research team took a range of readings and as a result of their modelling concluded that additional atmospheric observations would be able to effectively predict sea ice distribution and severe weather phenomena over the Arctic Ocean.

“Those of us with ongoing experience in the Polar Regions are well aware of the gaps in weather info and forecasting,” says Snider. “I cover exactly that in my book and in all courses that I teach and presentations that I make. Mariners are entering a region here-to-fore not frequently travelled, with extremely little infrastructure one would expect in other global coastal regions and hampered by inadequate communication making even regular receipt of information problematic if not impossible in many operating areas.”

As well as his role on Mirai, Snider is now involved with a project to further define the “practical” needs of Arctic weather forecasts. “My part is to contribute the experienced Arctic mariners perspective on what is presently missing with respect to current met and ice information and what is missing in forecasting.

“The Arctic Ocean is a huge expanse of nothing, surrounded by land mass with the occasional weather observation station. Because we have relatively little historical met/weather data for the region within the Arctic Ocean, and little knowledge of how weather systems generate, evolve and dissipate in this region, the forecasting in general is rather hit and miss.

“At least in the major oceans there are thousands of ships transiting every day contributing detailed weather data, and historical data is extensive. In my opinion, weather events have always been fairly unpredictable in the Arctic compared to temperate ocean areas. Even in the Antarctic, as it is land based and well covered with observation sites, prediction is generally more reliable. The project on Mirai from 2013, then in 2014 was an international effort to try and close the knowledge gap.”

Polar shipping is increasing. “The new traffic tends to be less experienced operators and less capable ships, both of which in my mind underscore the great need for improvement,” says Snider. “The experienced hands and highly capable ice ships operating in the past could (pardon the pun) generally weather the storms.”

The research continues with the Japanese researchers participating in a Polar Prediction Project study that will run from mid-2017 to mid-2019. The project is part of an initiative started in 2011 by the World Meteorological Congress that recognizes the growing need for safe Arctic travel. Its aim is to develop a Global Integrated Polar Prediction System that is based on better understanding of weather phenomenon such as polar clouds, sea ice and ice sheet dynamics. Enhanced modelling will then be used to improve weather predictions across a wide range of time scales.

Images: Captain David Snider

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.