[Photos] Saving the Steamship SS United States

She was called the unsinkable ship, built in 1912 to the latest technological developments of her time and the highest standards of luxury, so that only the super-rich of the time could afford for her palatial staterooms. Tragically, RMS Titanic sank at her maiden voyage at great loss of life and property, one of the greatest disasters in history.

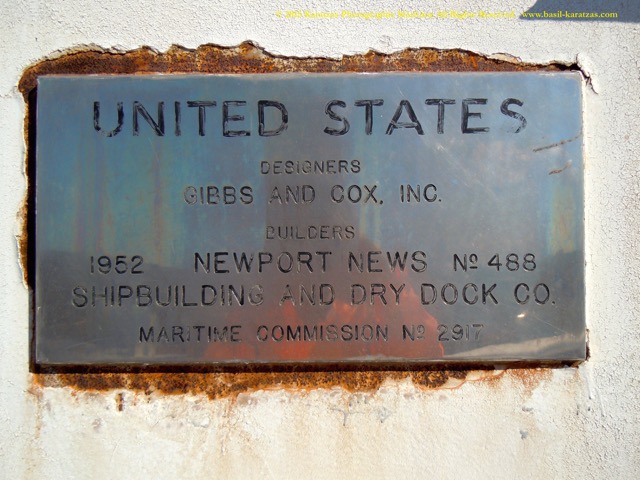

Four decades later, a longer, beamier, stronger, more powerful passenger vessel would be built in the U.S. at the Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company in Virginia. Her maiden voyage also made great news but for the right reasons, as she crossed eastbound the Atlantic Ocean in record time of about three days and eleven hours.

Soon thereafter, she crashed the record for the more challenging westbound leg of the Transatlantic trip with a record of almost three days and twelve hours. She earned the Blue Riband, the trophy for the fastest average cruising speed on both directions of the round Transatlantic voyage, a record that she still holds today, six decades later.

Her speed may have placed her name on the record books, but she has been a remarkable ship in more ways than one. With 990ft length overall, she was 110ft longer than RMS Titanic, and well within comparison to the 1,000-ft length commanded by today’s supertankers and monster container ships. Despite her length, her beam was kept narrow at 101ft so that she could pass gracefully through the Panama Canal if her voyage called for it.

Her steam turbines were capable of producing 248,000 shaft horsepower (SHP) – more than twice the power of today’s either typical supertanker or a two-engined Boeing 777 airplane. She brought the Blue Riband to American shores from the mighty Queen Mary by sailing as fast as almost 36 knots (approximately 41 mph), which is believed to be even today the fastest crossing of the Atlantic Ocean ever by a commercial ship (her actual top speed has never been published, as it was considered a state secret).

Her steam turbines were capable of producing 248,000 shaft horsepower (SHP) – more than twice the power of today’s either typical supertanker or a two-engined Boeing 777 airplane. She brought the Blue Riband to American shores from the mighty Queen Mary by sailing as fast as almost 36 knots (approximately 41 mph), which is believed to be even today the fastest crossing of the Atlantic Ocean ever by a commercial ship (her actual top speed has never been published, as it was considered a state secret).

The vessel was launched in 1952 at a contract price of $78 million, or approximately $690 million in today’s purchasing power. With 4,060 berths, her contract price was 50 percent more expensive than today’s cruise ships. Efficiencies in shipbuilding can attribute to savings, but SS United States was distinctly a luxury vessel with half of her passengers traveling in first class (versus one-third on RMS Titanic) and she had one crew member for every two passengers (versus one crew member for every three passengers on RMS Titanic.)

The high cost of the vessel was also partially attributed to increased specifications for military use, as less than a decade after World War II and with the Cold War just settling in when she was built, the U.S. government wanted access to passenger vessels in order to move rapidly military troops worldwide in the event that military action flared up again.

Although the vessel could accommodate up to three thousand passengers on a commercial voyage, five times as many (15,000) soldiers would be transported on one of the vessel’s military trips. As such, the vessel’s hull was built with re-enforced steel in order to sustain hostile fire and she was heavily compartmentalized with water-tight doors and bulkheads in order to prevent heavy flooding.

For the right of having access to the vessel in time of emergency, the U.S. Navy paid $50 million of the contract price, while $28 million was paid by her official shipowner and manager, the now defunct United States Lines (signage of the company can be seen today along the Chelsea Piers on the Hudson River in Manhattan.)

There were 12 decks (by comparison, the cruise ship Norwegian Breakaway, built almost sixty years later and the biggest cruise ship calling New York City these days, has eighteen decks) and plentiful luxurious common areas for the enjoyment of her privileged passengers, amenities such as indoor and outdoor promenades and sundecks, huge library with high ceilings and large, sunny windows in the front of the ship, ball room and dance floor with a dome structure, theater stage, tennis court, an elevator to the master staircase, a luxurious bar opening to the sun deck in the rear of the vessel, a swimming pool complete with sand around it for the passenger’s enjoyment.

There were 12 decks (by comparison, the cruise ship Norwegian Breakaway, built almost sixty years later and the biggest cruise ship calling New York City these days, has eighteen decks) and plentiful luxurious common areas for the enjoyment of her privileged passengers, amenities such as indoor and outdoor promenades and sundecks, huge library with high ceilings and large, sunny windows in the front of the ship, ball room and dance floor with a dome structure, theater stage, tennis court, an elevator to the master staircase, a luxurious bar opening to the sun deck in the rear of the vessel, a swimming pool complete with sand around it for the passenger’s enjoyment.

All such luxury had to be dispensed without the presence of wood on board the vessel in order to avoid fires. Extensive use of aluminum substituted for wood, and Steinway himself had to demonstrate that the specially made piano for the ship was fire proof and could actually cannot be set on fire (the piano and the butcher’s block were the only two wooden pieces ever allowed on board.)

With two 65ft-tall, brilliantly red-painted funnels, an almost vertically raked bow and round spoon-shaped stern typical for ocean liners of that age, SS United States cut a graceful figure over the water and on the horizon and her New York City port calls have been immortalized on numerous post cards.

Even today, the fainted red color of the two funnels is an eye-catcher when one is crossing the bridge approaching Philadelphia and from afar form the Seaport up the Delaware River; almost like two faint, red candle flames over the horizon, two candle flames of the memory and glory, a prayer that the wind of modern times will not peel off the colorful existence altogether.

In her 800 Transatlantic crossings over her seventeen year career ending in 1969 (about one crossing per week), notable politicians and celebrities enjoyed unparalleled luxury in her fast and graceful slide over the ocean: Marlon Brando, Coco Chanel, Sean Connery, Gary Cooper, Walter Cronkite, Salvador Dali, Walt Disney, Duke Ellington, Judy Garland, Cary Grant, Charlton Heston, Bob Hope, Marilyn Monroe, Prince Rainier and Grace Kelly, Elizabeth Taylor, John Wayne, and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor are known to travelled with her.

Four U.S. presidents sailed on board SS United States overtime, Harry Truman, Dwight Eisenhower, John Kennedy and Bill Clinton; the last, as fresh graduate from Georgetown, was on his way to study at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar in 1968, one year before the retirement of the vessel.

Four U.S. presidents sailed on board SS United States overtime, Harry Truman, Dwight Eisenhower, John Kennedy and Bill Clinton; the last, as fresh graduate from Georgetown, was on his way to study at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar in 1968, one year before the retirement of the vessel.

Ever since her retirement from active duty in 1969, the ship has been having a tumultuous life seeking a purpose and a permanent home. She has changed ownership several times since then, with buyers hoping to find commercial uses for her. She was designed as a passenger liner vessel to travel fast, and her conversion to a cruise ship or theme vessel or a floating hotel is not absolutely ideal, as she’s too narrow by her beam and her fuel consumption (replacing diesel powered steam turbines) will be high.

She has been gutted internally and most of the asbestos has been removed, so she’s ready for her next development stage. There have been proposals for her to be developed as a museum or theme vessel and relocated to major metropolitan areas, possibly New York, perhaps along the historic aircraft carrier Intrepid or find a place with Vision 2020: New York City Comprehensive Waterfront Plan.

The vessel was the obsession of the famous naval architect William Francis Gibbs who designed the original vessel almost two decades before her launching. Always unsuccessful at sourcing financing, faithfully he kept updating the design over the course of two decades, incorporating the latest developments in naval architecture and marine engineering.

When he saw an opening after WWII that the Federal Maritime Commission under the auspices of a politician with a soft spot for the maritime industry, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Gibbs proved equally skilled navigating the Washington bureaucracy to obtain partial financing for the construction of the vessel, and the fulfillment of a decade long love affair.

Now, an arthritic, gracious, old lady past her prime waits, barely cared about by today’s grandchildren of history, sits in her figurative attic at Pier 82 on the Delaware River in Philadelphia.

At present, the vessel is owned and controlled by the SS United States Conservancy (http://www.ssusc.org/), an non-for-profit organization, under the leadership of Susan L. Gibbs, the granddaughter of ingenious William Francis Gibbs, the naval architect and marine engineer who designed SS United States (and also notably the vessels that would be known as Liberty Ships during WWII.)

Through sizeable donations and ongoing fund raising efforts, the Conservancy has kept a close watch over the vessel and her constant need for upkeep and continuous cleaning efforts. However, a couple of recent proposals for the ship’s development have fallen apart, and the running costs of keeping the vessel at her present location are more than $60,000 per month.

Through sizeable donations and ongoing fund raising efforts, the Conservancy has kept a close watch over the vessel and her constant need for upkeep and continuous cleaning efforts. However, a couple of recent proposals for the ship’s development have fallen apart, and the running costs of keeping the vessel at her present location are more than $60,000 per month.

While “unsinkable” RMS Titanic got crushed by fate soon in her maiden voyage, SS United States, more than sixty years after she was launched from a navy shipyard, still stands tall, a testament to her shipbuilder’s ambition for building a ship that “you cannot catch her, you cannot set her on fire and you cannot sink her.”

However, the vessel that could not be sunk can be torched. After several false starts, the recent development efforts have unexpectedly been falling short, and the foundation has geared up a now-or-never effort to save the vessel as funding gets depleted by the end of this month.

For a vessel so closely associated with the aspiration and dreams of the United States to rule the waves of the world, a vessel so closely associated with the ascend of the United States to the world scene after WWII, it will be a shame for this vessel to be scrapped.

The passage of time is a brutal reminder that everything has an expiration date on our planet, especially for floating structures, but some such floating structures are just too close to our history, to our tradition, to the baton we eventually will pass to the future generations…

Please consider donating for this worthy cause at the website of the SS United States Conservancy website.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.